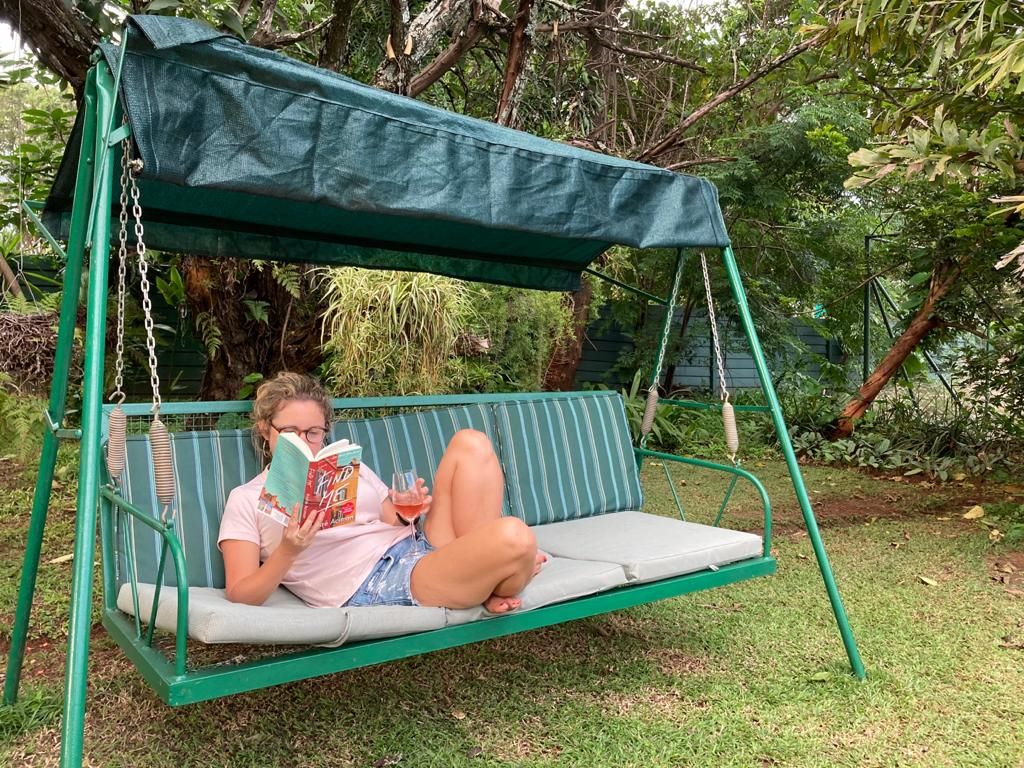

Never ever read the sequel to any novel you have loved. I take this as a general rule. There’s a risk that what you found heart-breakingly unique is in fact a tired old trick of that particular author, and the novel you love will be tainted in retrospect. I broke this rule by reading FIND ME, a sequel to the wonderful CALL ME BY YOUR NAME, and yes, it was a big mistake.

CALL ME BY YOUR NAME is the story of Elio, and his teenage infatuation. It a powerful and terrifying story of the one who got away. In FIND ME, the father of Elio, who is in his fifties, meets a beautiful twenty-something woman on a train, and they begin a wild romance.

I mean, okay. I’m not saying this could never happen, but for sure in this telling it seems unlikely. Even if you assume a lot of unspoken daddy issues, there is just no way a 24 year old is referring to some old guy’s penis as a ‘lighthouse’ and listening to him talk awkwardly about Goethe. I don’t want to be super harsh, but it kind of read like an extended and slightly pitiful exercise in wishful thinking by a middle-aged man.

Part way through the book we go back to Elio himself, who is now in his thirties. And there I had to stop. So far it had just been such a lot of unmotivated and unlikely drivel, I just couldn’t face the character being polluted by more of the same. So luckily I can’t tell you how it turned out.