Read for work so just adding for the record.

Tag: male writer

UNDER THE SKIN by Michael Faber

Here is a fantastically wonderful book with an amazing twist, so I recommend stopping reading this post right now and getting the book, because this is going to be full of SPOILERS.

The book begins with a woman picking up hitchhikers. This is so abnormal in the modern world that you can only assume she must be a serial killer. The hitchhikers do indeed die, and there is an extremely clever, slow reveal as to why. SHE’S AN ALIEN AND SHE’S ABDUCTING THEM AS A CULINARY DELICACY FOR HER HOME PLANET.

You’d think, based on this, it would be a science fiction story. It’s not at all. Mostly you are in head of the woman. Like many non-aliens, she hates her job, hates her boss, has a crush on someone who isn’t interested. At one point, some of the captured hitchhikers escape. They have been with the aliens for a month:

Removed from the warmth of its pen, it was pathetically unfit for the environment, bleeding from a hundred scratches, pinky-blue with cold. It had the typical look of a monthling, its shaved nub of a head nestled like a bud atop the disproportionately massive body. Its empty scrotal sac dangled like a pale oak leaf under its dark acorn of a penis. A thin stream of blueish-black diarrhoea clattered onto the ground between its legs. Its fists swept the air jerkily. Its mouth opened wide to show its cored molars and the docked stub of its tongue.

‘Ng-ng-ng-ng-gh!’ it cried.

She has occasional moral scruples about how they are treating the humans. But as she explains at one point, they “couldn’t siuwil, they couldn’t mesnishtil, they had no concept of slan . . . And when you looked into their glazed little eyes, you could understand why.” It’s clearly, among many, many, other things, a meditation about vegetarianism, and how we train ourselves to not have compassion. And not just for animals, but for sweatshop employees, for children affected by air pollution, and all the other things that make the world go round.

At one point we do visit the processing plant, where one of the recently de-tongued hitchhikers writes the word MERCY on the ground. The alien pretends to a wealthy visitor that she does not know what it means, as she does not want do-gooders getting hysterical. And indeed there is no such word in the alien language in any case. Later, when things go wrong with a hitchhiker, and he is trying to rape her (luckily she lacks human genitals), she is terrified, and tries to remember the word. “Murky!” she screams. It’s not everyday you laugh at a rape scene.

The aliens’ home planet is some kind of toxic stew, where oxygen and water are expensive and must be fought for. Thus, much of the book is spent with the alien marvelling at beauty of the countryside around the A9 highway. It is tragic to see our ‘ordinary’ world through her eyes. She is amazed we have still got sky and sea to enjoy. For a little while, anyway.

COMING UP FOR AIR by George Orwell

This is a book about a man who does not succeed in blowing up his life. He is an insurance salesman, married with two children, and labouring under a mortgage. (In a sign that things were better back then, the mortgage is only for sixteen years. WTF is up with London housing)

One day he conceives a desire to go fishing, as he was an avid fisherman as a boy. He has not however fished since he was sixteen. Here’s why:

In this life we lead – I don’t mean human life in general, I mean life in this particular age and this particular country – we don’t do the things we want to do. It isn’t because we’re always working. . . . It’s because there’s some devil in us that drives us to and fro on everlasting idiocies. There’s time for everything except the things worth doing. Think of something you really care about. Then add hour to hour and calculate the fraction of your life that you’ve actually spent doing it. And then calculate the time you’ve spent on things like shaving, riding to and fro on buses, waiting in railways junctions, swapping dirty stories and reading the newspapers.

He bunks off from his family to go and spend a week in the village in which he grew up, which he has not seen in twenty years. In his mind ‘as permanent as they pyramids,’ he arrives to find it now just an outer suburb of London, and not an especially nice one at that. He buys a fishing rod and does not use it. He sees an old girlfriend, and is horrified and how old she looks. Fat and with false teeth himself, he assures us that men never go so far downhill as women do. Sometimes the patriarchy is really adorably deluded.

He ends up going home, concluding there is no escape from his life. The year however is 1938, and the book has hanging over it very explicitly the coming war. You feel he will almost welcome it.

Side point. Orwell published a bunch of books you’ve never heard of, including this, and then in 1945, Animal Farm; and in 1949, the novel 1984. Then in 1950 he was dead, at 47. Imagine: he managed to squeeze in two seminal classics just before the end. Imagine what would have come next. Imagine how close to the wire he cut it.

SHUGGIE BAIN by Douglas Stuart

About ten pages into this book, I felt like I was getting into a hot bath. I just got ready to seriously relax. It’s exactly the sort of book I like: one that gives you a break from your own life, by deeply involving you in someone else’s.

It tells the story of a little boy being raised on some quite rough council estates by his alcoholic mother. I would bet heavy money that this book, while marketed as fiction, is based on the author’s own childhood. There is a certain subset of books in which the detail of daily life is so vividly captured that it can only come from a child’s eye, and ideally a child with a ton of trauma. It’s Glasgow in the 1980s, a place and a time I’ve never given a second thought to, and now I feel like I have a real experience of it. It joins such bizarrely disparate periods as Trinidad in the 1950s (courtesy, A HOUSE FOR MR BISWAS) and the Dominican Republic in the 1960s (courtesy, FEAST OF THE GOAT read on a particularly hallucinatory 12 hour bus ride to Acupulco).

I won’t go on about everything I thought was wonderful about this book, but let me just leave you with this:

The other taxi drivers had taken on that familiar shape of men past their prime, the hours spent sedentary behind the wheel causing the collapse of their bodies, the full Scottish breakfasts and the snack bar suppers settling like cooled porridge around their waists. Eventually the taxi hunched them over till their shoulders rounded into a soft hump and their heads jutted forward on jowled necks. The ones who had been at the night shift a long time had turned ghostly pale, their only colour was the faint rosacea from the years of drink. These were the men who decorated their fingers with gold sovereign rings, taking vain pleasure from watching them sit high and shiny on the steering wheel

And that’s just taxi drivers! Imagine everything else that’s in there

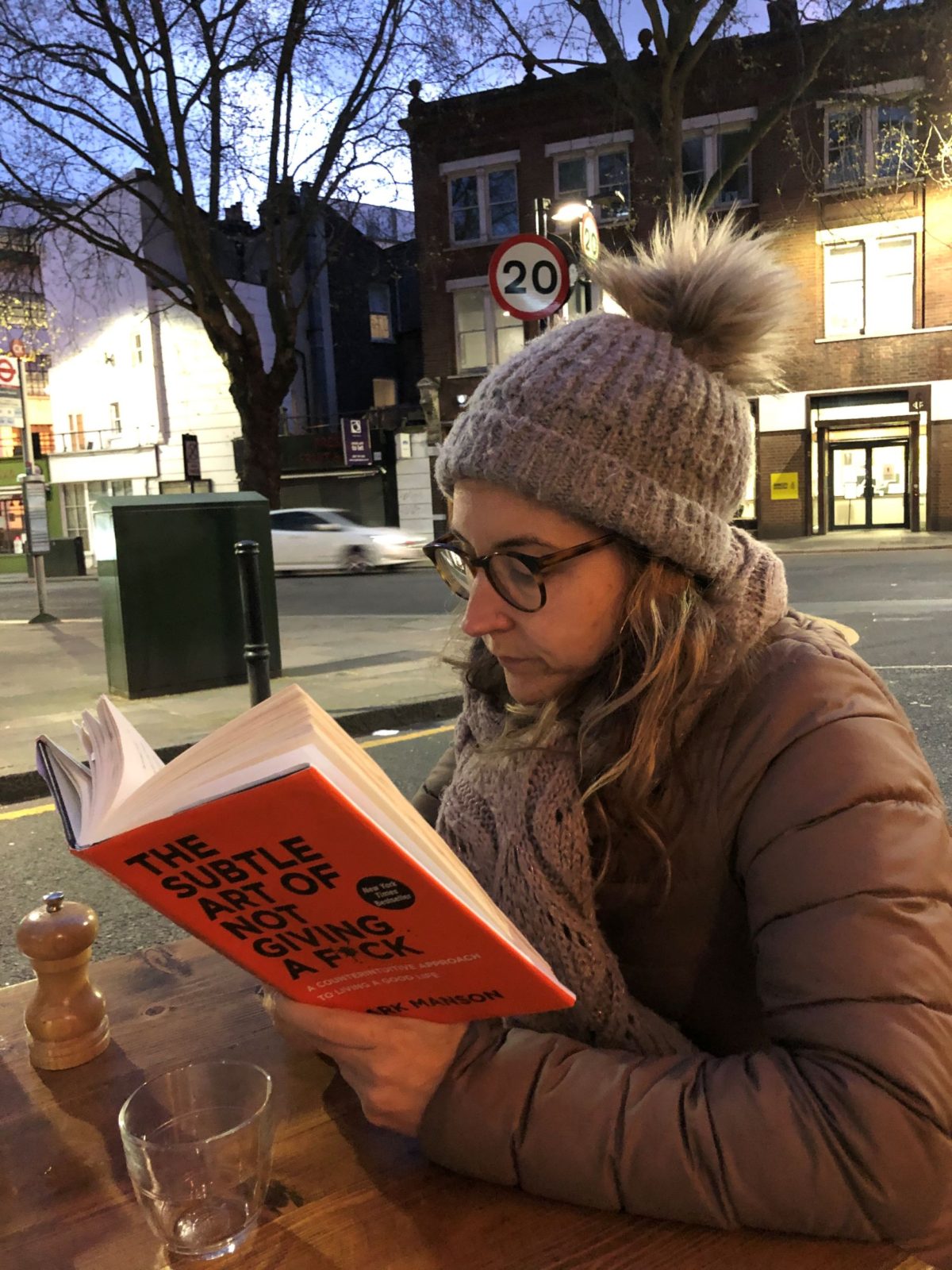

THE SUBTLE ART OF NOT GIVING A F*CK by Mark Manson

Here is an example of how a great title does half the work. Though the author’s point is not so much that we should not give a f*ck, but rather that we should only give a f*ck about what we give a f*ck about. Easier said than done, in my experience. I often find myself getting riled up about things that I know I do not care about. In any case, the book is refreshing in its emphasis that there is no life without problems; the point is to choose the right problems.

I also thought this was useful:

If you want to change how you see your problems, you have to change what you value and/or how you measure failure/success.

Here his point is, don’t measure success too much based on things you cannot control, e.g., the approval of others, promotions, etc. Rather focus on things you can control, e.g., doing your best. Associated with this is what you should measure yourself on:

Redefine your metrics in mundane and broad ways. Choose to measure yourself not as a rising star or an undiscovered genius. . . . Instead, measure yourself by more mundane identities: a student, a partner, a friend, a creator. . . . (You should) define yourself in the simplest and most ordinary ways possible. This often means giving up some grandiose ideas about yourself: that you’re uniquely intelligent, or spectacularly talented . . . This means giving up your sense of entitlement and your belief that you’re somehow owed something by this world.”

I can’t say it’s the best written or most insightful book I’ve ever come across, and admittedly I lost it in an Uber before I finished it completely, but that said I enjoyed it.

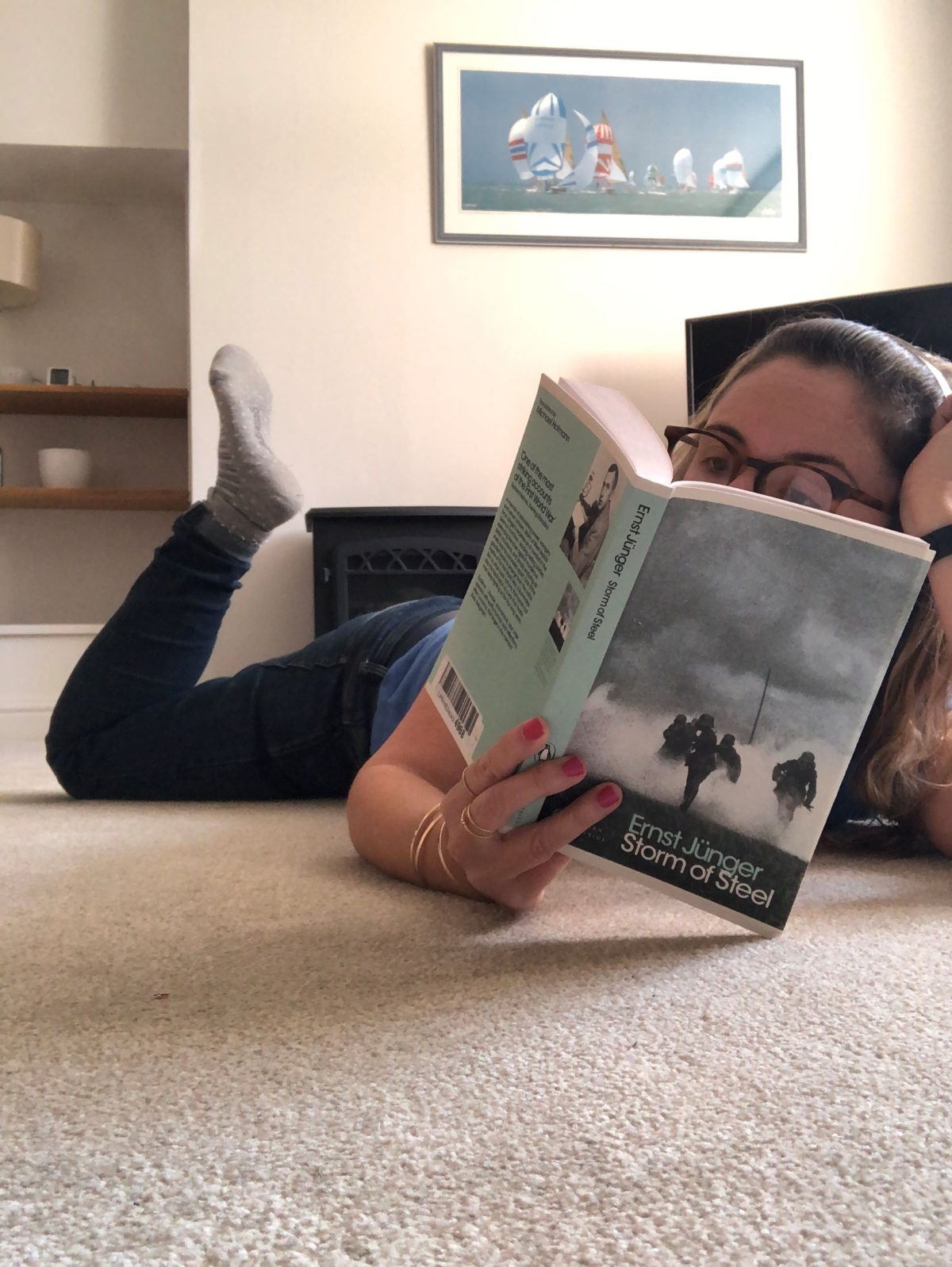

STORM OF STEEL by Ernst Junger

Here is a book about how bad things can get. It’s the dairies of a man who signed up on the the day the first world war began, and, incredibly, made it all the way through to 1918. The Somme, Ypres, Cambrai: he saw them all.

The book was published in 1919, and it shows. Most of the other books of this period were written at a remove of at least a decade or so, but in this one there has been no time to make sense of the war, or to do anything but just tell us what happened. It is in parts boring, as war is boring, and in other parts horrifying. As far as I can tell, no one whom he personally knew with whom he began the war ended it alive with him.

It is deeply revolting. Here he is on a patch of land that has been fought over repeatedly:

In among the living defenders lay the dead. When we dug foxholes, we realized that there were stacked in layers. One company after another, pressed together in the drumfire, had been mown down, then the bodies had been buried under the showers of earth sent up by shells, and then the relief company had taken their predecessors’ place. And now it was our turn.

He is on the German side, and is, as ever, extraordinarily depressing to see how very similar their war was from their alleged ‘enemies’ on the other side. He is even reading TRISTAM SHANDY in the trenches. Towards the end, though, his war does differ from that of English accounts I have read, because he is of course, losing, and he knows it. They start to run out of food; they are no longer sleeping in trenches, but in craters; and still he goes on.

With every attack, the enemy came onward with more powerful means; his blows were swifter and more devastating. Everyone knew we could no longer win. But we would stand firm.

He is clearly losing it.

A profound reorientation, a reaction to so much time spent so intensely, on the edge. The seasons followed one another, it was winter and then it was summer again, but it was still war. I felt I had got tired, and used to the aspect of war, but it was from familiarity that I observed what was in front of me in a new and subdued light. Things were less dazzlingly distinct. And I felt the purpose with which I had gone out to fight had been used up and no longer held. The war posed new, deeper puzzles. It was a strange time altogether.

It is in this context that he goes into his last battle. His company takes a direct hit, and twenty some young men are killed right next to him. Then he goes on for hours, fighting, sobbing, singing. At one point he takes off his coat, and keeps shouting “Now Lieutenant Junger’s throwing off his coat” which had the “fusiliers laughing, as if it had been the funniest thing they’d ever heard.” He cannot remember large stretches of this last battle. At one point he stops to shoot an Englishman, who reaches into his pocket and instead of bringing out a pistol brings out a picture of family. Junger lets him live. He kills plenty of others though, including one very young man:

I forced myself to look closely at him. It wasn’t a case of ‘you or me’ any more. I often thought back on him; and more with the passing of the years. The state, which relieves us of our responsibility, cannot take away our remorse; and we must exercise it. Sorrow, regret, pursued me deep into my dreams

And all this while HE KNOWS THEY CANNOT WIN. Guys, I would have deserted long before, and I am not even ashamed to say it. Honour, like courage, are concepts generally deployed by rich people to get you to do what they want. I can’t think of almost anything for which I would die.

NOTHING TO SEE HERE by Kevin Wilson

This was a re-read of this marvellous book about income inequality and spontaneous human combustion.

I didn’t love this the second time round as much as the first. But this still has me loving it more than most books. This time round what I concluded is that what makes it remarkable is the quality of the voice of the narrator. It’s weirdly, painfully, contemporary and disillusioned.

Try this, about her efforts to get a scholarship to a school for rich kids:

I didn’t know the school was just some ribbon rich girls obtained on their way to a destined future. . . . . I wasn’t destined for greatness, I knew this. But I was figuring out how to steal it from someone stupid enough to relax their grip on it.

I won’t write up the whole book again; the first read is here. If you are looking for something to read, I recommend it.

THE LAST PICTURE SHOW by Larry McMurtry

In this book some teenage boys have sex with a blind cow. And this is not even the climactic center of the book. Apparently this is just part of normal small town life in Texas. The author is famous for his novels that draw on his own upbringing in small town Texas, so I guess this is based on true events. This just goes to show you what I have always thought, which is that small towns are not charming as people try to claim, but in fact dangerous and creepy. (See also scarring movie WICKERMAN, but only if you want to be scarred.)

“We could go on down to the stockpens,” Leroy suggested. “There’s a blind heifer down there we could fuck.” . . . . The prospect of copulation with a blind heifer excited the younger boys almost to frenzy, but Duane and Sonny, being seniors, gave only tacit approval. They regarded such goings on without distaste, but were no longer as rabid about animals as they had been. . . In the course of their adolescence both boys had frequently had recourse to bovine outlets. At that they were considered overfastidious by the farm youth of the area, who thought only dandies restricted themselves to cows and heifers. The farm kids did it with cows, mares, sheep, dogs, and whatever else they could catch . . . It was common knowledge that the reason boys from the diary farming communities were so reluctant to come out for football was because it put them home too late for the milking and caused them to miss regular connection with the milk cows.

IS HE JOKING. At least in the play EQUUS this kind of thing is given the dignity of being a major plot point. Here it’s not. This story is about this young man, Sonny, who is graduating high school. He is having an affair with a middle-aged woman who is in a marriage people casually assume is abusive. (Sample: “I don’t understand how Mrs Popper’s lasted,” Duane said). Sonny drops her the second the local popular girl shows an interest. It’s a sad as it sounds. As a middle-aged woman myself, it fills me with renewed gratitude to be alive now, with my own income and my own Tinder if I want it.

Even all the side plots are sad: he falls out with his best friend, who then blinds him in one eye (?) before heading off to fight in Korea. The only apparently positive figure is the local poolhall owner, Sam the Lion, who looks after a young disabled boy called Billy (you don’t want to know how he is involved in the cow thing). Then he dies. Because this is the kind of book this is. It’s so sad it gets into the ridiculous. Everyone was lonely , everyone was not getting enough sex, or getting the wrong sex, or etc. Life is not all sad, just like it is not all happy.

Larry McMurtry is a great writer, so still I enjoyed it. But if you’ve never tried him, I recommend you start with his Pulitzer winner LONESOME DOVE (which this blog tells me I read a solid ten years ago)

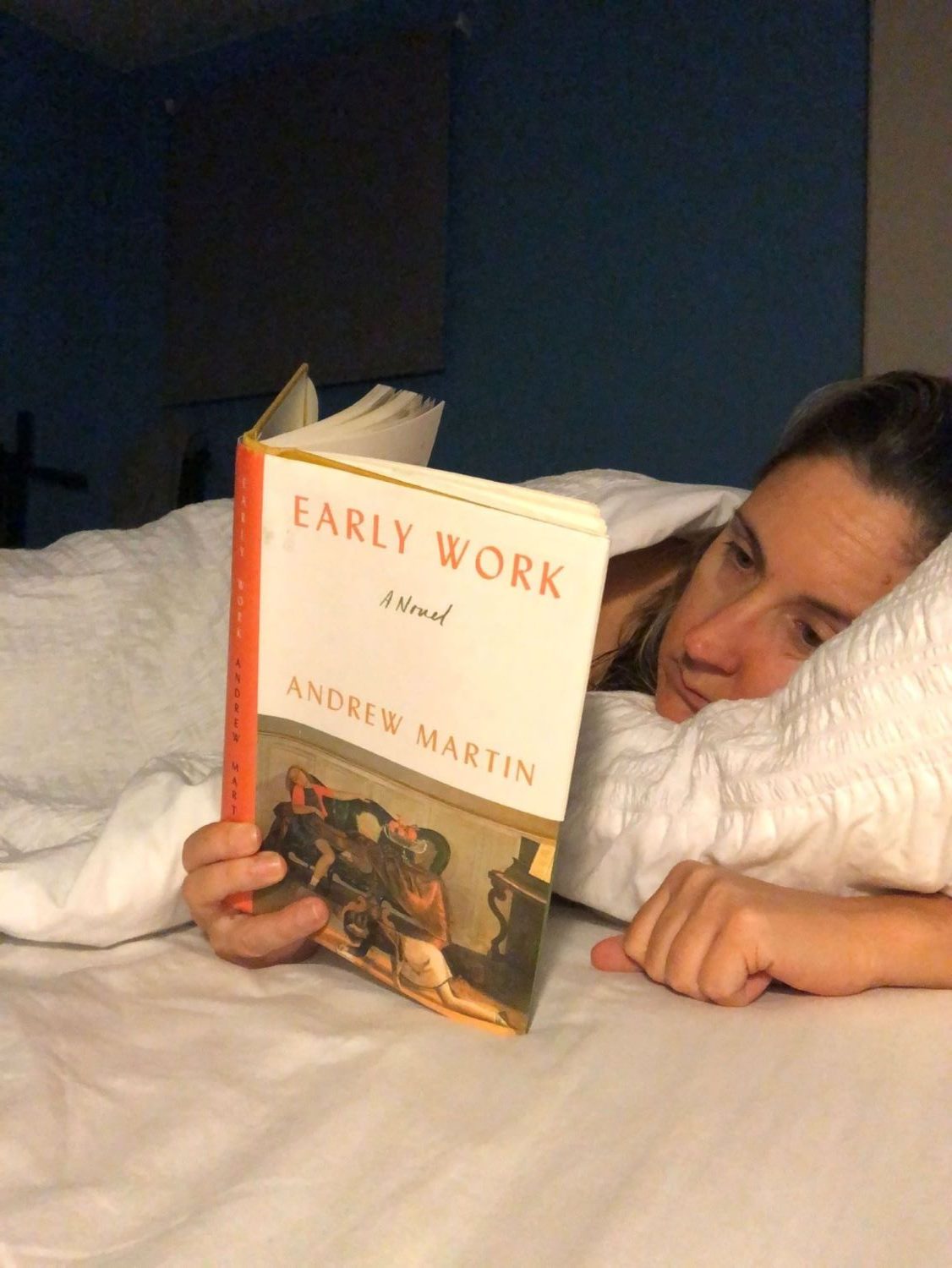

EARLY WORK by Andrew Martin

This is my third reading of this amazing book (first two are here and here). This time round I re-read it to try and understand how it works. I hoped to understand something about the mystery of good writing, but I am left even more mystified than before. It is so WONDERFUL. How did Andrew Martin DO it? Every other line is funny, and the remainder are either touching or insightful. Did it take him ONE THOUSAND YEARS? A further mystery is this, WHY DON’T MORE PEOPLE LOVE IT? Like how can it be that someone can write such a near perfect novel and the world not close down? That’s the arts for you, I guess. You achieve something near impossible and nobody much cares.

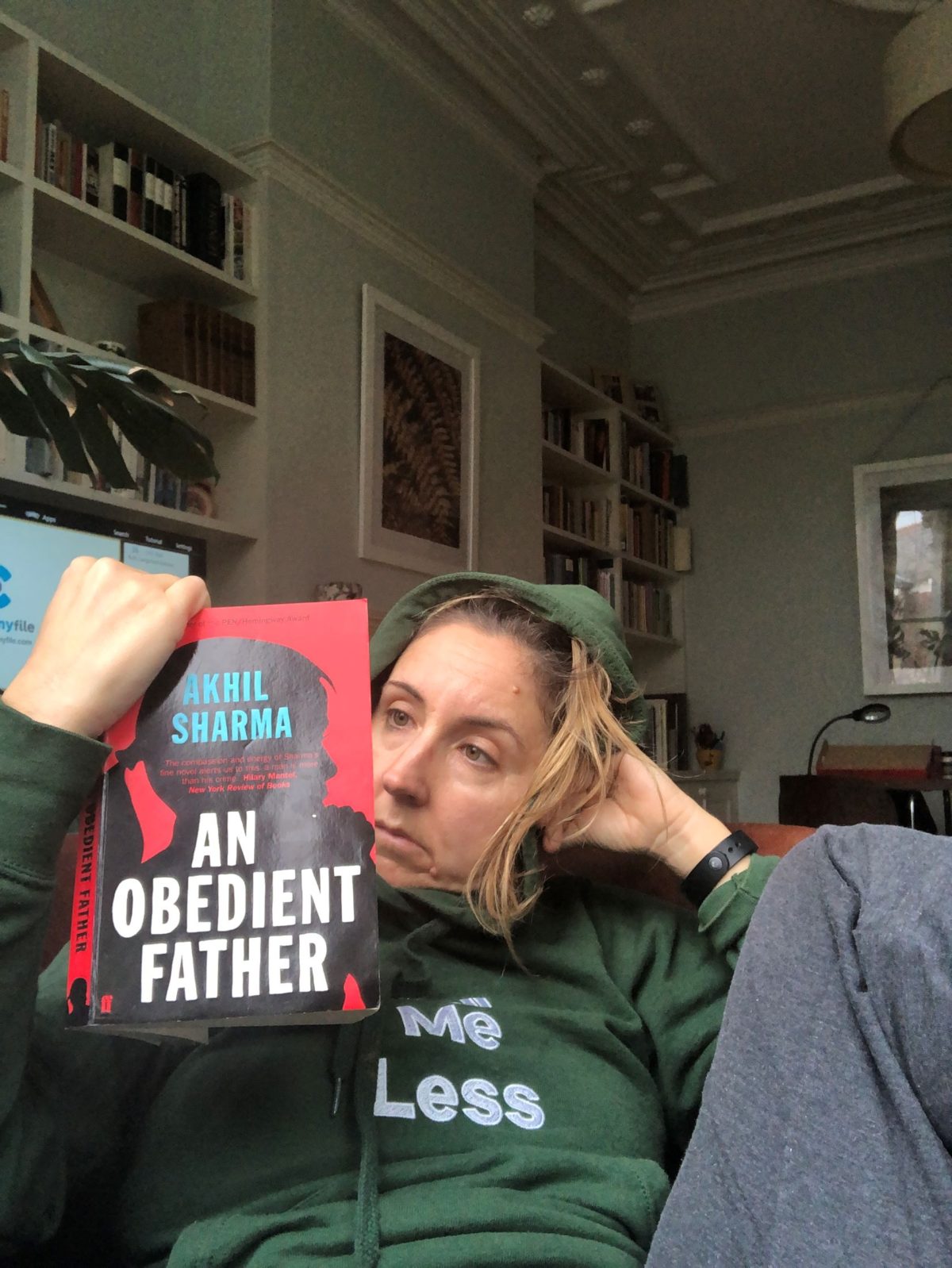

AN OBEDIENT FATHER by Akhil Sharma

I had to give up on this book because it was just too believable. It tells the story of a child abuser, from the perspective of the child abuser. Fiction exists to help us understand others. This is a noble goal. But I guess I just don’t really want to understand all others.

In theory, I suppose we all agree that everyone’s human. Like, even Hitler. And Ted Bundy. And I guess I’ve read quite a few books from the perspective of dictators and serial killers, which I’ve never found it too revolting before. This one though: wow. It’s enough to make me wish there is a hell, so that fathers who rape their children can go there.

As I debated whether or not to give up on this book , I spent quite some time thinking about why it was so unreadable. I think its because at least a serial killer, you think, okay, you are crazy. You are working out some mania. And dictators, okay, they kill people, but at least they are like obsessed with a greater Deutschland or whatever. This guy: he rapes her for a while, and then when he gets caught he stops. So he’s not a maniac. He just wanted to rape her and so he did.

Anyway, I feel gross just writing about it. If you think you can stomach it, though, I will say it is startlingly well written, just like Akhil’s previous book FAMILY LIFE). It’s set in India and in addition to the abuse is also a grim look at how unavoidable petty political corruption is. God no wonder I had to quit.