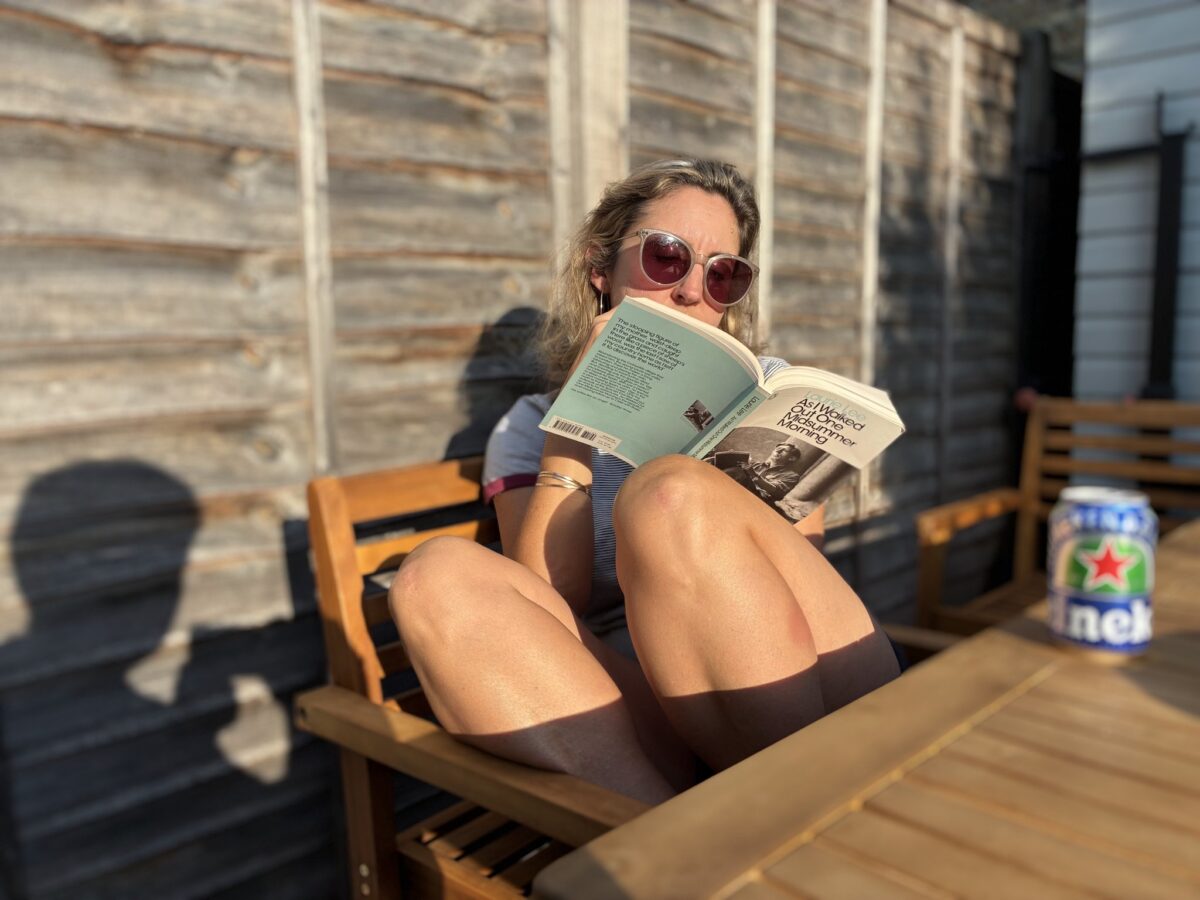

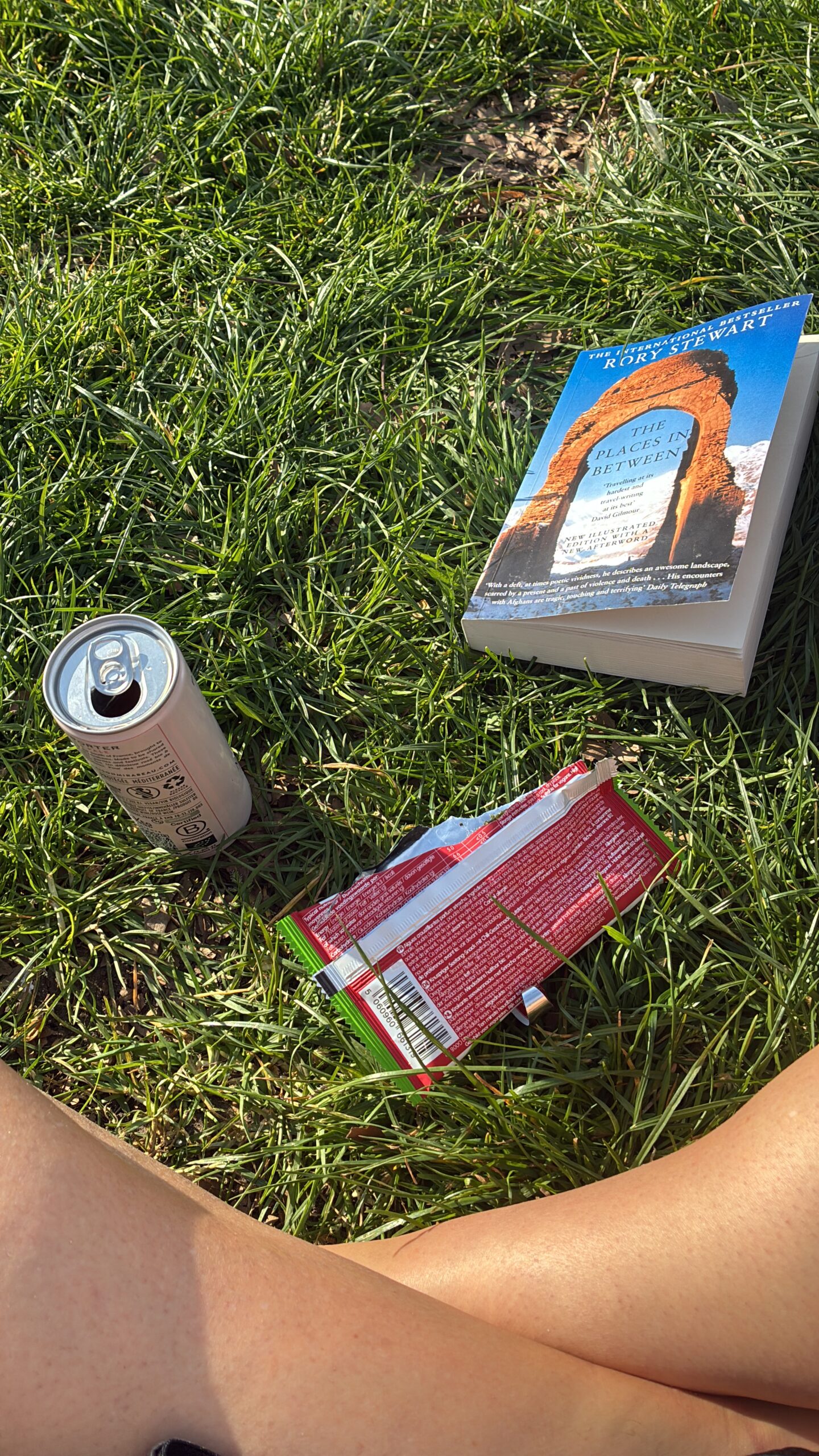

Here is a classic memoir of being a young man. It’s 1932, and Laurie sets out from his rural home to walk to London, bidding farwell to his (I assume exaggeratedly) elderly mother. First he walks to Southampton, as he has never seen the sea. Try this charming description of the seaside shops: “tatooists, ear-piercers, bump-readers, fortune-tellers, whelk-bars, and pudding boilers.”

Pudding boilers! Then he goes to London, where he has some pretty intense country-mouse style experiences, and then he is on to Spain, where he walks many miles through extraordinarily rural communities, busking to pay his way. He is a fantastic writer. Here he is, entering an inn:

“The narrow stairs dripped with greasy mysterious oils and had a feverish rotten smell. They seemed specially designed to lead the visitor to some act of depressed or despairing madness. I climbed them with a mixture of obstinancy and dread, the Borracho wheezing behind me. Half-way up, in a recess, another small pale child sat carving a potato into the shape of a doll, and as we approached she turned, gave us a quick look of panic, and bit off its little head. “

And I can’t go to a seafood restaurant without thinking about: “The dead eyes of fish, each one an ocean sealed and sunless.”

He writes the memoir as a much older man, and there is an elegiac quality to the whole thing. Here he is describing the sensation of his body on these long walks:

“. . seems to glide in warm air, about a foot off the ground, smoothly obeying its intuitions. . . It was the peak of the curve of the body’s total extravagance, before the accounts start coming in.”

God, the accounts.

I have thought often of this book since reading it. There is something about the freedom of this walk, with no goal, no time limit, no agenda, that is really a challenge to my current life. Also the safety of being a young man – imagine, just sleeping in a field, and not thinking you’ll be raped and murdered! Horrifyingly though, my main reflection was mostly about how he did all this without a phone. Apparently he often just used to lie down in the heat of the day, and watch the ants, for hours. Imagine doing all this without even a podcast! Truly I need to get off my phone.

At the end he does what apparently everyone young did if they were in Spain in the 1930s, i.e., naively enter the civil war. This part was dumb.