The blog tells me I read 67 books this year, one more than last year, and more than any year since 2011. One reason I keep this blog is as a reminder not just of the books, but of what the books carry with them, which is memories of where they were read. PREP, first book of the year, was in a Zimbabwean garden. SHUGGIE BAIN was read in part at a London coffee shop when we were finally allowed outdoor dining again. LEAVING CHEYENNE I bought in a tourist trap in South Dakota. ZINKY BOYS was the beach in Croatia. WOW, NO THANK YOU was a flight to Corfu. MEATY was a five hour delay in Amsterdam airport.

I did an unusually large number of re-reads of old and beloved friends (EARLY WORK, THE LOVE AFFAIRS OF NATHANIEL P, THE PURSUIT OF LOVE, and NOTHING TO SEE HERE). I used to not re-read, but I do it increasingly. I think because I realize that there are not so many good ones out there in the world to be found. I also read a larger amount of non-fiction and self-help (I can recommend FOUR THOUSAND WEEKS if you want to feel like blowing up your life). Mostly it was fiction though, and it was a banner year. I struggled to narrow the list of my favourties, so did not bother:

Every book SAMANTHA IRBY has written: (here, here, and here). I put off this writer for some time, having the impression this was a book of essays was – as so many are – a book of thinly disguised lectures about gender/race/etc. In fact they are a brilliantly sad and funny, and make you feel less alone in the world.

UNDER THE SKIN by Michael Faber. A story about aliens, but from the aliens’ perspective. Let me tell you, whatever you think it is about, it is not about that. Just drop everything and read immediately

OUR SPOONS CAME FROM WOOLWORTHS by Barbara Comyns. A thinly disguised story of her own first marriage. She wants to be an artist, and she marries an artist, but once a baby comes apparently what she wants doesn’t matter anymore. A timeless story of being f*cked by gender roles, and very funny. My one favourite part is that her husband, who to be fair to him, really SUFFERS for his art as he leaves his wife and child to starve, was not a success and is now totally forgotten. My other favourite part is the amazing biography of the author on the first page, which covers her careers including poodle breeding, house selling, and painting, showing you do not need to sacrifice all to art to be an artist.

ALL MY CATS by Brohumil Hrabal. I don’t know if I enjoyed it, but I thought about it a lot. It’s one of the only books I’ve ever read about our relationship to our pets, and it investigates how difficult it is to keep boundaries around love

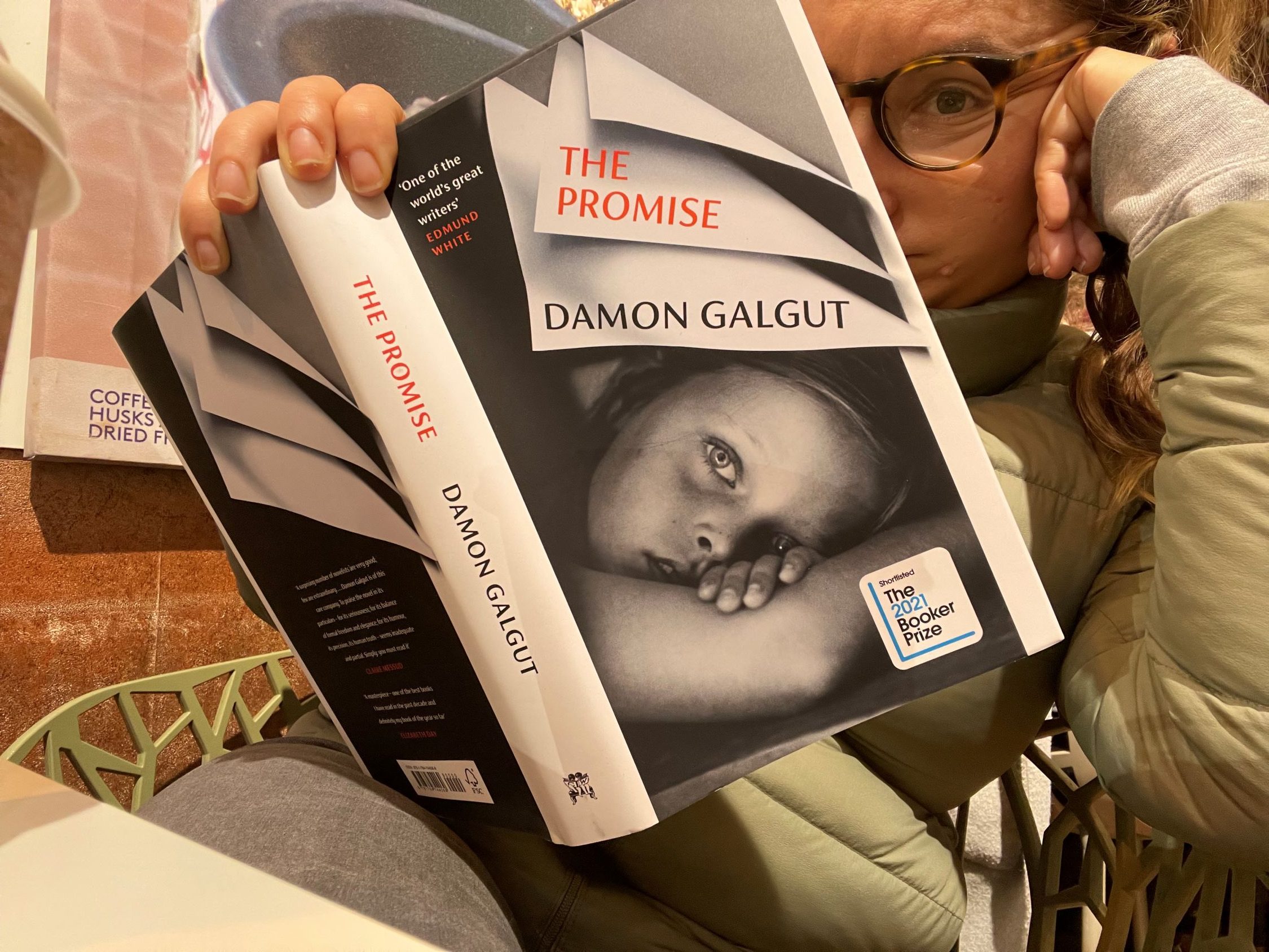

So far these are all backlist (and in Comyns case, almost a century old), but I also enjoyed the American and British blockbusters this year, CROSSROADS by Jonathan Franzen, and SHUGGIE BAIN by Douglas Stuart. It’s fashionable to hate on Franzen, and I get the impulse, but I think we have to give it up: the man can write.

Here’s to having less time to read in 2022 because COVID will be OVER.

The list:

FOUR THOUSAND WEEKS by Oliver Burkeman

SOMETIMES I TRIP ON HOW HAPPY WE COULD BE by Nichole Perkins

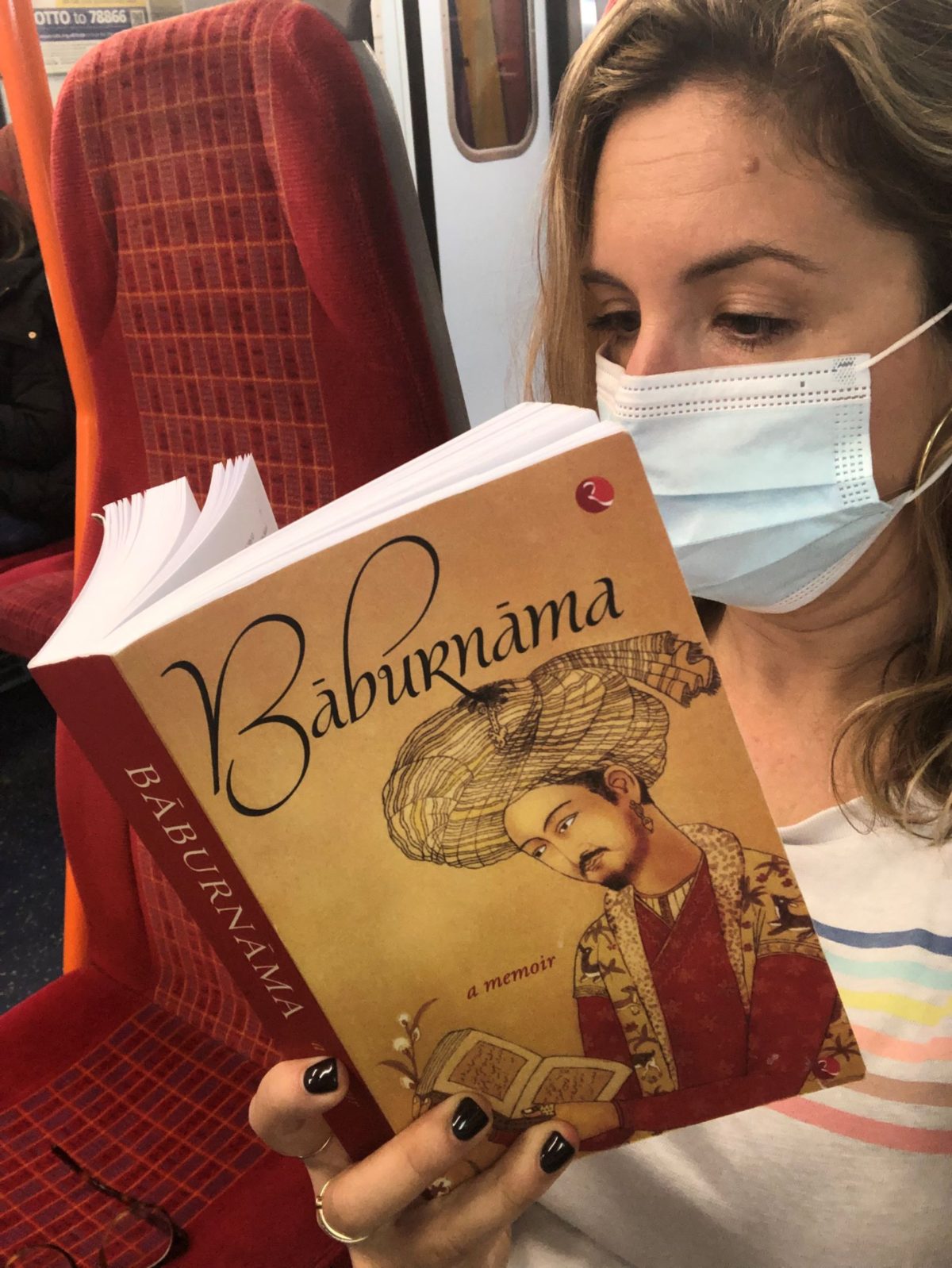

BABURNAMA by Babur trans. Annette Beveridge

THE GRAND SOPHY by Georgette Heyer

WISE BLOOD by Flannery O’Connor

WE ARE NEVER MEETING IN REAL LIFE by Samantha Irby

ONE FAT ENGLISHMAN by Kingsley Amis

SWEET SORROW by David Nicholls

THE DUD AVOCADO by Elaine Dundy

THE MAN IN THE HIGH CASTLE by Philip K Dick

CROSSROADS by Jonathan Franzen

STAY SEXY AND DON’T GET MURDERED by Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark

BEAUTIFUL WORLD, WHERE ARE YOU by Sally Rooney

OUR SPOONS CAME FROM WOOLWORTHS by Barbara Comyns

SH*T MY DAY SAYS by Justin Halpern

THE ANIMALS IN THAT COUNTRY by Laura Jean McKay

FOREIGN AFFAIRS by Alison Lurie

WOW, NO THANK YOU by Samantha Irby

AND THEIR CHILDREN AFTER THEM by Nicolas Mathieu

ZINKY BOYS by Svetlana Alexievich

LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE by Laura Ingalls Wilder

THE LYING LIFE OF ADULTS by Elena Ferrente

FALSE COLOURS by Georgette Heyer

THE PURSUIT OF LOVE by Nancy Mitford

WINTER IN THE BLOOD by James Welch

LEAVING CHEYENNE by Larry McMurtry

CROSSING SAFELY by Wallace Stegner

THE TRIALS OF RUMPOLE by John Mortimer

THE DEVIL IN THE FLESH by Raymond Radiguet

LOVE LETTERS by Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West

THE DRIVER’S SEAT by Muriel Spark

ALL MY CATS by Brohumil Hrabal

BATH TANGLE by Georgette Heyer

A BURNT-OUT CASE by Graham Greene

STRANGER IN THE SHOGUN’S CITY by Amy Stanley

LITTLE EYES by Samantha Schweblin

UNDER THE SKIN by Michael Faber

COMING UP FOR AIR by George Orwell

THE LOVE AFFAIRS OF NATHANIEL P by Adelle Waldman

SHUGGIE BAIN by Douglas Stuart

THE ENDS OF THE EARTH by Abbie Greaves

THE SUBTLE ART OF NOT GIVING A F*CK by Mark Manson

STORM OF STEEL by Ernst Junger

NOTHING TO SEE HERE by Kevin Wilson

THE LAST PICTURE SHOW by Larry McMurtry

SOME TAME GAZELLE by Barbara Pym

AN OBEDIENT FATHER by Akhil Sharma

THE INVENTION OF NATURE by Andrea Wulf

THE HANDMAID’S TALE by Margaret Atwood

WAR AND TURPENTINE by Stefan Hertmans

DEPT OF SPECULATION by Jenny Offill