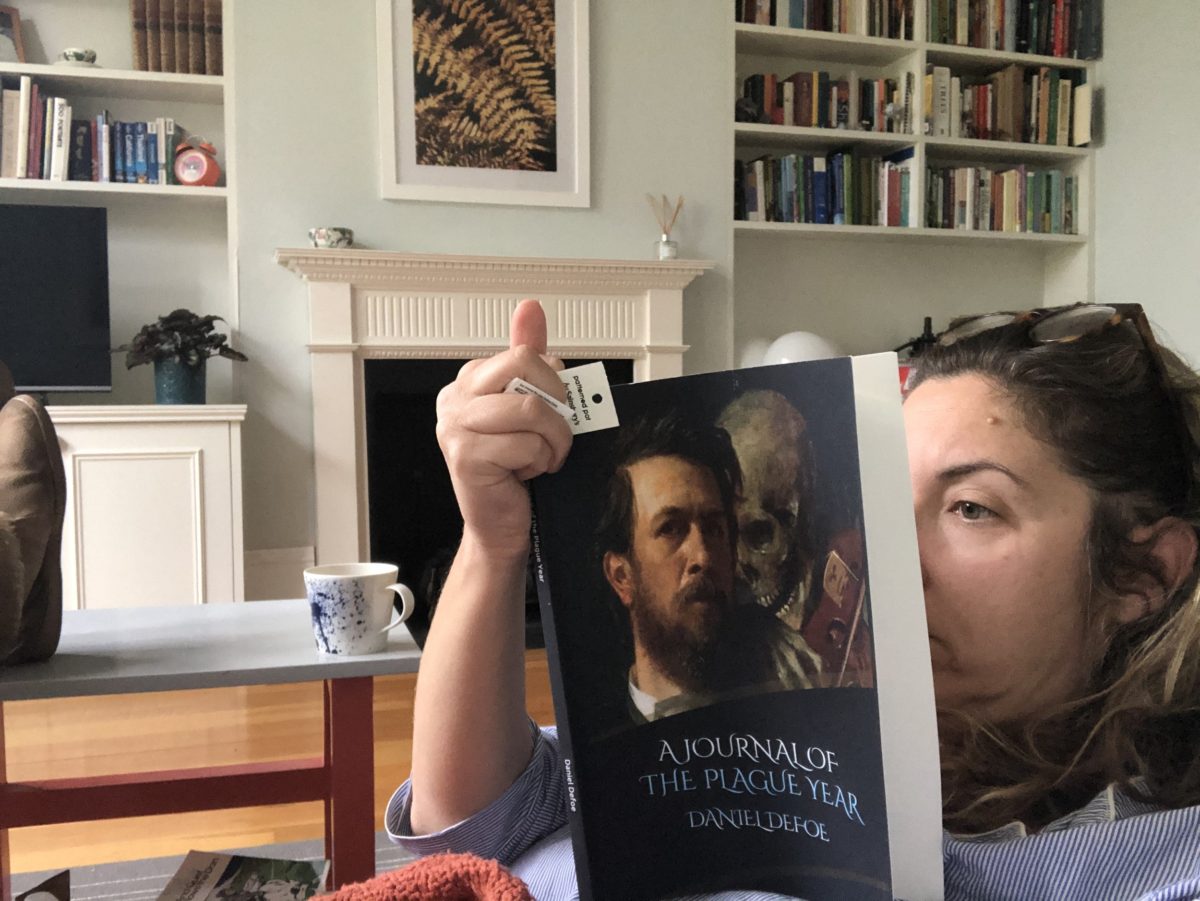

I thought this would be pandemic appropriate reading. Apparently this thought of mine has already been predicted at scale, because someone has emergency published a edition and put it on Amazon. Truly, if people are looking to seventeenth century literature for their margin, then nothing is safe. I’m going to go ahead and call it: this truly is late capitalism. I don’t know what comes after this, but I’m pretty sure it’s not going to be good.

Perhaps this is dramatic. The past is not usually so very different from the future. I learn from this book is that the last pandemic to hit London (the bubonic plague in 1664) is not so very different from this one. Try this:

We had no such thing as printed newspapers in those days to spread rumours and reports of things, and to improve them by the invention of men, as I have lived to see practised since. But such things as these were gathered from the letters of merchants and others who corresponded abroad, and from them was handed about by word of mouth only; so that things did not spread instantly over the whole nation, as they do now.

I see then as now they were shocked by how quickly things went viral.

The story is about a man who, unlike most wealthy people, decides to try and ride out the plague in town, rather than rushing to the country. While Defoe did not actually live through the plague, his uncle did, and most people believe this is pretty fair evocation of what it was like. Just like today, it was hardest for the poorest:

The truth is, the case of poor servants was very dismal, as I shall have occasion to mention again by-and-by, for it was apparent a prodigious number of them would be turned away, and it was so. And of them abundance perished, and particularly of those that these false prophets had flattered with hopes that they should be continued in their services . . .

The rich meanwhile fled easily, carrying the plague with them all over the country. Those left behind as today found ways to work through it. Shops made you put your money in a bowl of vinegar before your touched it.

Other things were not like today. While this vinegar thing does not sound like a bad idea, they had some much worse ones. Lots of people thought writing ABRACADBRA on a piece of paper and tying it around your neck would do the trick. Perhaps I just need to clarify, for those people who believe that e.g., 5G causes corona, but that is does not in fact work. Indeed they had ‘dead carts’ circling around eery night, and they would holler, “Bring out your dead,” so they could take them to the pits. Let’s end on this long piece about the pits.

I went all the first part of the time freely about the streets, though not so freely as to run myself into apparent danger, except when they dug the great pit in the churchyard of our parish of Aldgate. A terrible pit it was, and I could not resist my curiosity to go and see it. As near as I may judge, it was about forty feet in length, and about fifteen or sixteen feet broad, and at the time I first looked at it, about nine feet deep; but it was said they dug it near twenty feet deep afterwards in one part of it, till they could go no deeper for the water; for they had, it seems, dug several large pits before this. For though the plague was long a-coming to our parish, yet, when it did come, there was no parish in or about London where it raged with such violence as in the two parishes of Aldgate and Whitechapel.

I say they had dug several pits in another ground, when the distemper began to spread in our parish, and especially when the dead-carts began to go about, which was not, in our parish, till the beginning of August. Into these pits they had put perhaps fifty or sixty bodies each; then they made larger holes wherein they buried all that the cart brought in a week, which, by the middle to the end of August, came to from 200 to 400 a week; and they could not well dig them larger, because of the order of the magistrates confining them to leave no bodies within six feet of the surface; and the water coming on at about seventeen or eighteen feet, they could not well, I say, put more in one pit. But now, at the beginning of September, the plague raging in a dreadful manner, and the number of burials in our parish increasing to more than was ever buried in any parish about London of no larger extent, they ordered this dreadful gulf to be dug—for such it was, rather than a pit.

They had supposed this pit would have supplied them for a month or more when they dug it, and some blamed the churchwardens for suffering such a frightful thing, telling them they were making preparations to bury the whole parish, and the like; but time made it appear the churchwardens knew the condition of the parish better than they did: for, the pit being finished the 4th of September, I think, they began to bury in it the 6th, and by the 20th, which was just two weeks, they had thrown into it 1114 bodies when they were obliged to fill it up, the bodies being then come to lie within six feet of the surface. I doubt not but there may be some ancient persons alive in the parish who can justify the fact of this, and are able to show even in what place of the churchyard the pit lay better than I can. The mark of it also was many years to be seen in the churchyard on the surface, lying in length parallel with the passage which goes by the west wall of the churchyard out of Houndsditch, and turns east again into Whitechappel, coming out near the Three Nuns’ Inn.

Okay, these pandemics are not that similar. I am so grateful for modern science. These anti-vaxxers, 5G-ers, climat change deniers: to the pits with them.