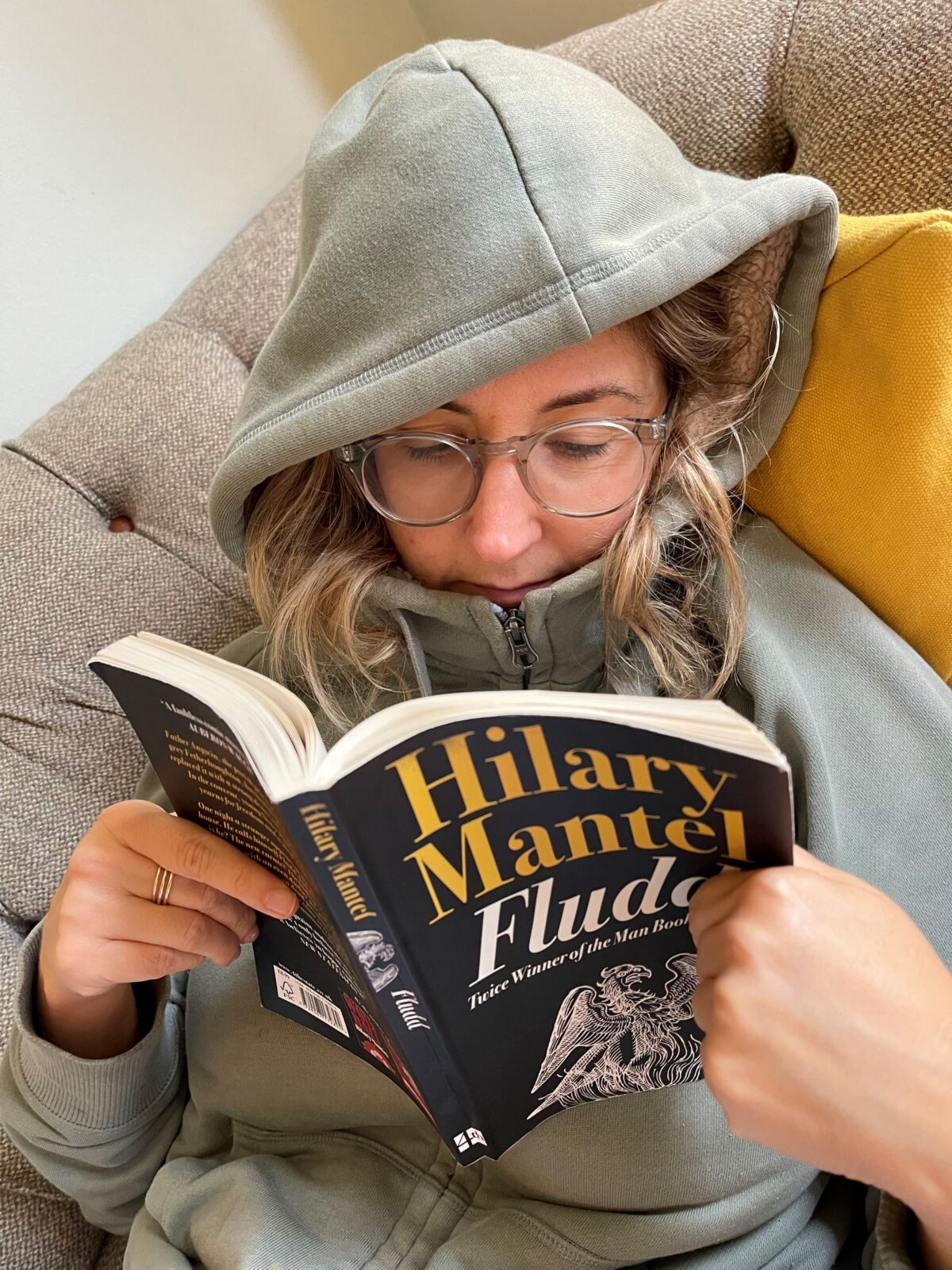

Hilary Mantel is a magical writer. I mean, try this:

There were draughts, it was true, which followed each worshipper like a bad reputation, which dabbed at their ankles and climbed into their clothes, as cats do with people who do not like them

Bam! Two amazing ideas in a row, and about draughts. Then try this one, about the view of Catholics towards Protestants in a small town:

The Protestants were damned, of course, by reason of this culpable ignorance. They would roast in hell. A span of seventy years, to ride bicycles in the steep streets, to get married, to eat bread and dripping: then bronchitis, pneumonia, a broken hip: then the minister calls, and the florist does a wreath: then devils will tear their flesh with pincers.

What an accurate summary of a life. And then this:

But then again, taking the long view, and barring flood, fire, brain damage, the usual run of back luck, people do get what they want in life. The frightening thing is that life is fair; but what we need, as someone has already observed, is not justice but mercy

And yet, in a an abrupt left turn, let me say that I did not really like this book. It was about a new curate coming to a parish church who turns out to be the devil. The plot really fell apart, and the book sort of petered out. But the beginning was so strong it was worth it. “What we need is not justice but mercy” GAR!