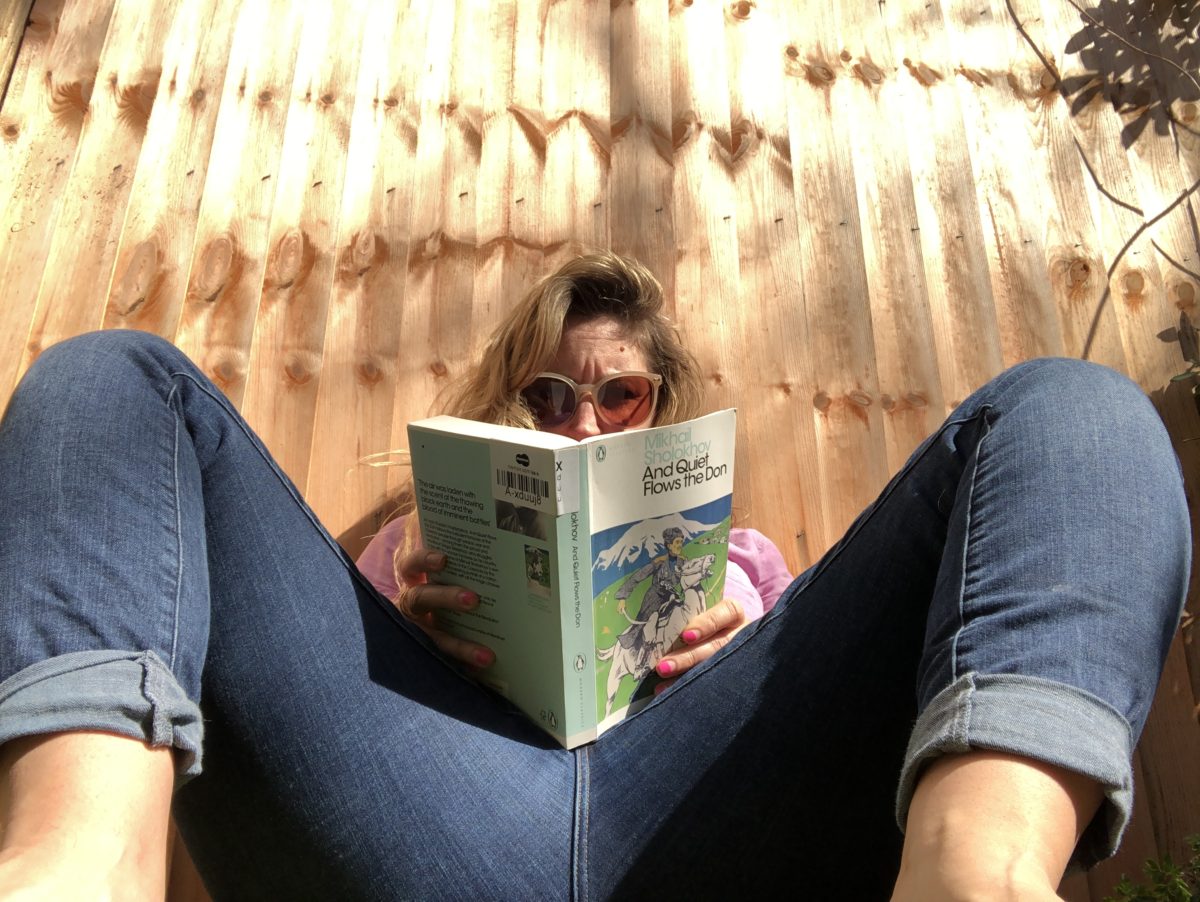

Here is a novel that assumes you have a much more detailed knowledge of the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks than in fact you do.

It begins in a Kossack village, and you learn all about the rural life and the casual rape of the early twentieth century. There is, as befits any self-respecting nineteenth century Russia novel, a big cast of characters, all of whom have multiple names. There is lots of bracingly Russian stuff. Here’s an old man:

It’s time – I’ve lived my days, I’ve served my Tsars, and drunk vodka enough in my day

Here’ a wife finding her husband drunk:

Daria thrust two fingers into his mouth, gripped his tongue, and helped him to ease himself

I mean I’ve heard of doing anything for love, but this is ridiculous. All of this is all just very much prep for what the author wants you to know about, which is the First World War, the Revolution, and the ensuing Civil War. The author was in involved in the two latter (from age of 13) and it shows. Try this:

All the objects around were distinct and exageratedly real, as they appear after a night’s unbroken watching

I love the suggestion that we all know what it is like after a night on sentry duty. He also appears to think we are all equally informed about Russian politics. The end of the book becomes a haze of revolutions and counter-revolutions. What was most interesting was to see how the idea that your class was more important than your country took over on the Russian side, and how many people escaped with their lives because of it.

The front broke to pieces. In October the soldiers had deserted in scattered, unorganized groups; but by the beginning of December entire companies, regiments, divisions were retiring from their positions in good order, sometimes marching with only light equipment, but more frequently taking regimental property with them, breaking into warehouses, shooting their officers, pillaging en route, and pouring in an unbridled, stormy flood-tide backto their homes.

You so want it to end well for them. I guess we know it did not. But at least a good chunk of these young men got the chance to live long enough to see it all go wrong