This book of personal essays was reviewed rapturously in the New York Times. I did not quite get it. You don’t need to have had an ‘interesting’ life to write interesting essays about that life. But this is not his problem – Fitzgerald does seem to have had an interesting life : Catholicism, bar work, porn work. And yet the essays were, for me at least, rather vanilla. It’s hard for me to imagine how you write a tame essay about your time in porn, but there you go, seems to have been done. I guess others loved this book, but it wasn’t for me.

Tag: male writer

TRAVELS INTO THE INTERIOR OF AFRICA by Mungo Park

Here are the deliriously wild real-life diaries of an English man’s solo effort to find the source of the Niger. He does not start off solo, but it goes that way pretty fast. In 1794 he is employed by some geographic association for the task, after the man who went before him “had fallen a sacrifice to the climate, or perished in some contest with the natives.”

He starts off from the Gambian coast, on foot. He meets a huge variety of people, and is an object of great interest. In many villages he spends hours taking on and off his coat for an audience who have never a white person, or a coat, before. In one village the women come in to find out from him if he is truly a man (!) and he volunteers to show ‘the youngest and prettiest one’ his penis. They find this hilarious.

I had always heard that one reason African people did not unite to fight off colonialisation is that they did not (understandably) immediately realize the threat, being too deeply involved in their own centuries-old conflicts. This book shows how that could be so, for a huge amount of it is about who is at war with who and what that means for Mungo. Also shockingly interesting is his estimate that only about one in four of the Africans he meets are free, the rest being slaves. (Apparently there were two levels, if you were a local, you had some rights, but if you were a foreigner you really had none)

Mungo gets robbed quite a bit, and eventually is actually imprisoned by some Arab nomads. He has more time than he wants to observe them, and notes that “ as (their) pastoral life does not afford full employment, the majority of the people are perfectly idle, and spend their day in trifling conversation . . .” WHERE DO I SIGN?

He also notes some pretty interesting female beauty standards: “A woman, of even moderate pretensions, must be one who cannot walk without a slave under each arm to support her, and a perfect beauty is a load for a camel.” He saw young girls sit weeping over their food, being forced to eat until they vomited, so they could grow fat. Again, WHERE DO I SIGN.

This part is pretty bleak actually, as the translator (a 9 year old boy) calmly explains to him that his captors are debating between putting his eyes out and murdering him. Eventually he escapes with only the clothes he is wearing and his horse. He is lost and has no water. He lies down to die, first letting his horse go (as the last ‘act of humanity’ he will ever do); and then it starts to rain. He manages to meet some more people and is able to exchange buttons on his waistcoat for food. It is hair-raising. Eventually he makes his way back to the coast, never having got near the source of the Niger, but returning to a hero’s welcome all the same. On his return, impoverished journey, it is pretty sad to see how who mostly helped him are the poor. He is grateful to tears when an old slave woman gives him a handful of mush.

I expected quite a lot of old school racism, but more got this:

“Whatever difference there is between Negro and the European in the conformation of the nose and the colour of the skin, there is none in the genuine sympathies and characteristic feelings of our common nature.”

CHARLOTTE GRAY by Sebastian Faulks

Here is a novel about a female spy. It starts as a straight-forward love story, then becomes an espionage novel, and then loses its way for a bit, struggling to connect the plotlines while getting deep into French politics in WWII.

It’s engaging throughout, which is a feat at 500 + pages, and is remarkable for deep research and believable characters, even when the plot is a little shaky. I was especially struck by the presentation of how ordinary French people reacted when their neighbours were collected into railway cars and sent ‘east’. How did they react? Apparently they were not just fine with it, they actively applauded. It is pretty chilling.

Also of interest was the worldview of those who signed up to the ideas of Vichy France: that is, that German was clearly going to win the war, so it made sense to accept this early and get France the best seat possible in the ‘new Europe.’ One can see the pragmatism of this view. It is darkly funny how completely wrong they were. What I learnt from this is that when you are being ‘pragmatic’ (i.e., dividing up your neighbours clothes between yourselves) you better make sure you are making the right bet, because if you are not, you are truly left with nothing, not even your dignity.

THE SUITCASE by Sergei Dovlatov

I picked up this book in the week Alexi Navalny died. It’s like a very tiny tribute to that remarkable and heroic tradition of Russian dissent of which he was an heir.

It begins: “So this bitch at OVIR says to me, “Everyone who leaves is allowed three suitcases. That’s the quota.” LOL! You know you are in for a good dictatorship story when it begins with encounters with bureaucracy. I myself have fond / horrifying memories of a certain 12 hour long queue to get a Zimbabwean passport in 2010.

The novel is structured around the stories of each of the items he was supposedly allowed to take out of Russia. It is both hilarious and sad. How hilarious is this:

Two hundred years ago the historian Nikolai Karamzin visited France. Russian emigres there asked him: “What’s happening back at home, in two words?”

Karamzin didn’t even need two words. “Stealing,” he replied.

A great book.

BEER IN THE SNOOKER CLUB by Waguih Ghali

This is a novel about an Coptic Egyptian dealing with some pretty modern problems. It’s the 1950s, he comes from money, he gets involved in the wrong side of of the revolution, he moves to Europe, and he becomes poor in that really penniless way that only intellectuals seem to be able to manage.

He suffers a lot, and I felt for him, but I also wanted to shake him. One of his big problems is that he doesn’t feel like he is ‘Egyptian,’ because he is relatively well off and a Copt (so speaks French and English rather than Arabic). There is nothing that annoys me quite so much as this unthinking agreement we all seem to have that you can only ‘really’ be part of a country if you are part of the majority of that country. When he moves to Europe he also does a lot of suffering, because he feels that while he has been on some level formed by European ideas he does not fit in there either. This also makes me want to shake him, and say: it’s fine to also not be part of Europe! A hybrid person is still a real person!!

These are I recognize all the struggles of the colonized intellectual, so perhaps that this seems so clear to me in the twenty first century is because I stand on the shoulders of those of the twentieth, who did the suffering for me. Poor Ghali, he killed himself in London in 1968.

THEY CAME LIKE SWALLOWS by William Maxwell

In case you feel like you have not had enough pandemic content, here is something for you. It’s about the 1918 flu, and is based on the author’s own experience of losing his mother to it when he was just 10 years old.

After the loss he was made to go and live with his aunt, so he lost not just his mother but his whole world. For this reason, the book is actually less about the flu itself and more a sort of memorial to the ordinary days of his childhood just before it.

What is particularly interesting is to be reminded of what childhood was like when boredom still existed. They spend hours in this book doing nothing much, being with their own thoughts. It’s strange to think what childhood is like now, when children have so many books and activities and phones and television. Imagine having to generate your own content!

POOR THINGS by Alasdair Gray

Here is an very fruity book about SPOLIER ALERT someone creating a living woman from the body of a dead woman and the brains of her fetus.

It was pretty interesting as a concept, but I found I struggled to care on some level. Everything was so wild and magically real that it was hard to feel that anything meant anything or would have any consequences. It made me think about FRANKENSTEIN, and especially why the monster in that book is male and not female. Because, let us face it, if some mad scientist in the nineteenth century thought he could bring someone back to life he would 1000% have tried with a woman because, obviously, sex slave. Perhaps because Mary Shelley was female it did not go in that direction, but you know realism-wise it ought to have. Also, I’ve just been in a Wikipedia deepdive about Mary Shelley, and let me give you the sobering reflection that she wrote FRANKENSTEIN when she was just 19! However she had already led a big life, having got together with Shelley when she was 16 (and he was married), after meeting him secretly at her mother’s grave (why), and then running away with him because even though it’s 1819 she believes in FREE LOVE. What a baller.

STAY TRUE by Hua Hsu

Here is a book about grief. It is written by someone born in the same year as me, and tells about his best friend in university, who died when he was a junior. It was eerie to read a book so exactly of my time-and-place. That rarely happens for me. I enjoyed this for example, something I had forgotten about:

Back then, years passed when you wouldn’t pose for a picture. You wouldn’t think to take a picture at all. Cameras felt intrusive to everyday life. It was weird to walk around with one, unless you worked for the school paper, which made picture taking seem a little less creepy.

I’d forgotten about a time before photos were the default.

The story was a sad one. What struck me was how much I now recognize what grief looks like: the guilt about what you could have done differently (oh GOD, the guilt), the retrospective wondering what your relationship meant, and etc. I can’t imagine how the author got together the emotional resilience to write it. I barely had the resilience to read it.

One thing I have been thinking about recently is how anytime someone dies, you read about them in the paper after a stabbing or whatever, there is almost always really bereft family and friends left behind. It’s kind of beautiful to think that every random person you see in the street is so surrounded by love.

MONKEY BOY by Francisco Goldman

It is strange how few books there are by immigrants, and how many by immigrants’ children. My theory is we immigrants are busy, trying to assimilate or live the capitalist dream or whatever, and it’s the children who have the free time to try and understand what just happened.

In this book an American man, the child of a Guatemalan and a Ukrainian Jew, puts the effort in. Some parts of it I found pretty interesting, like his flashbacks to middle school, and a particularly epic high school crush. Other parts were less interesting, like where he visits his mother in her retirement home, tirelessly grilling her about Guatemalan history despite her advancing dementia. I mean I get it: he is deep in middle age, and wants it all to have some meant something. Good luck with that I guess.

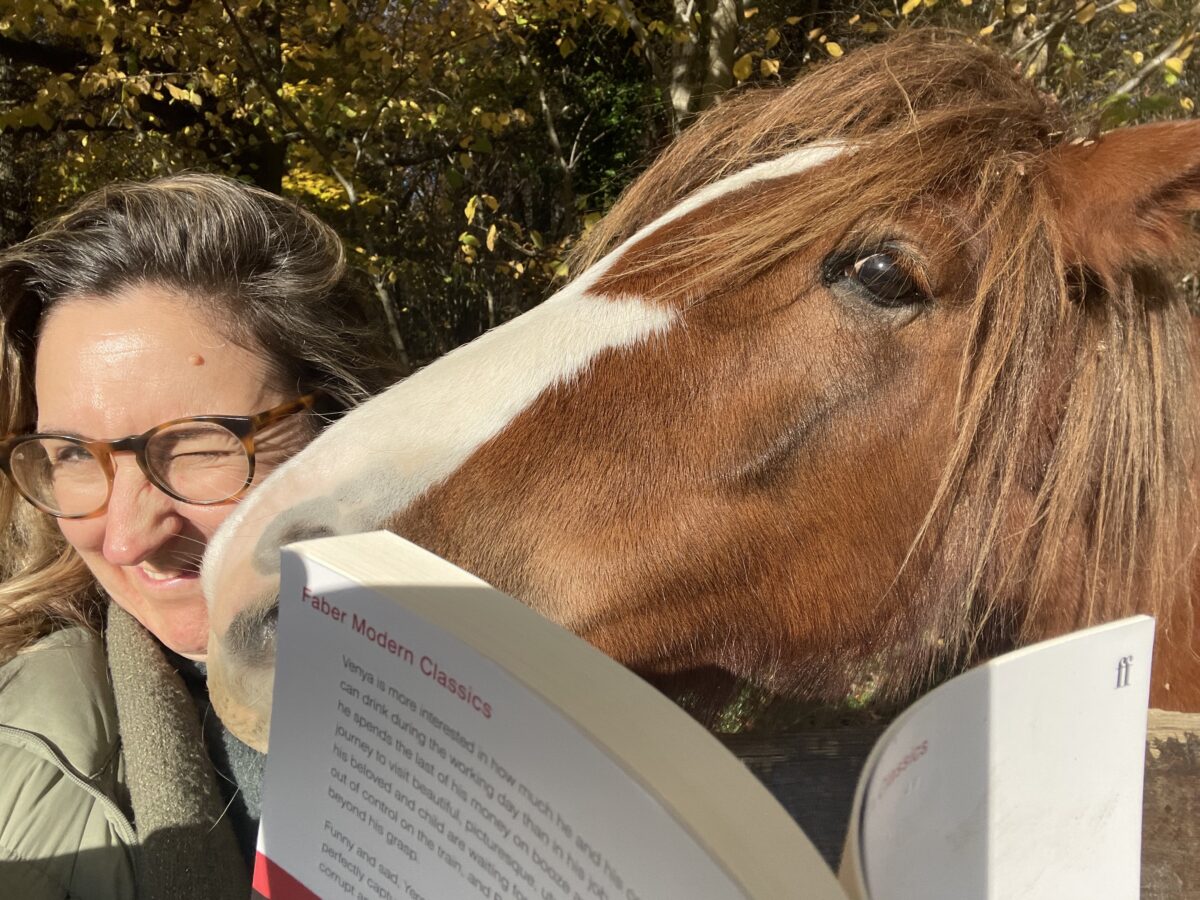

MOSCOW STATIONS by Venedikt Yerofeev

It boring to listen to other peoples’ dreams. It is also boring to be with drunk people babbling away while you are sober. This book is kind of a mix of these two kinds of borings. I feel bad to have to say it, as this is a famous classic of 20th century Russian literature, and the author had an eccentric, impressive, and difficult life. Like GULAG ARCHIPELAGO, it circulated on samizdat for many years before the government allowed it to be published (appearing in a magazine dedicated to education on the evils of drinking, though its unclear if the editor meant this as a joke or not). It tells the story of a man getting progressively drunker as he rides the train from Moscow to the suburb where his son lives. One interesting point to learn was how really rough Soviet alcoholism was. At one point the narrator tells us about one drink he makes, called ‘Dog’s Giblets,’ which involved mixing floor varnish and brown beer. This is not an exaggeration – apparently the author’s girlfriend used to hide her perfume when he came round, for he would drink it. I literally can’t imagine that status you have to reach to seriously consider the floor varnish, let alone the perfume