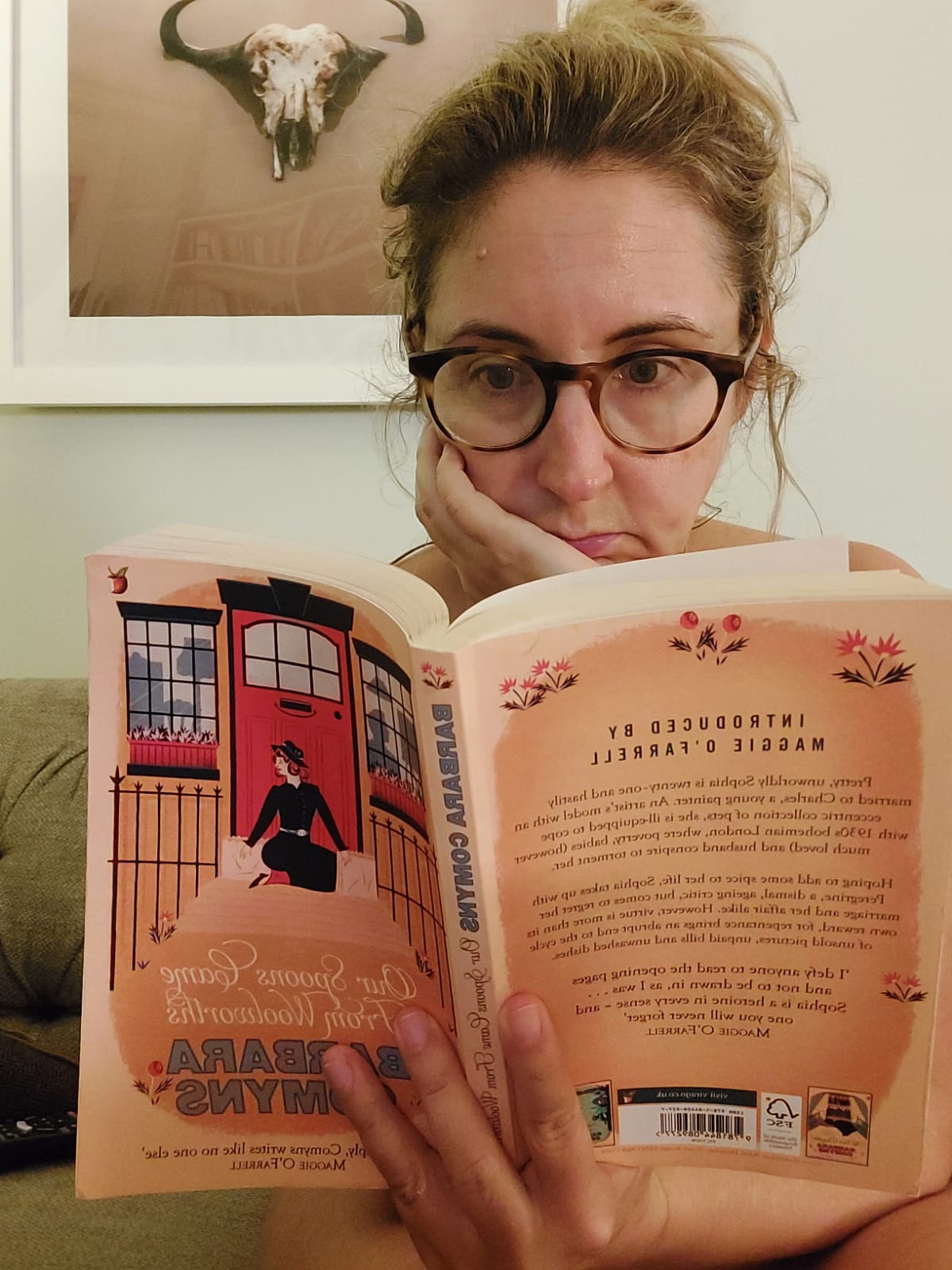

This is a strangely inspirational book about failed painting careers, poverty and abortion. It tells the story of a young female art student who marries another art student. She gets pregnant and they are both horrified. Bizarrely, because it is the 1930s, or because he does not understand biology, the husband blames her. He refuses to take any responsibility for the baby, insisting he must focus on his art. The wife understands, because she too wants to be an artist. But instead she gets to do menial jobs for money. Eventually they split up and she ends up on the street with her baby. She manages to pull herself out of the situation by leaving London and getting a job as a cook.

Reading this summary you might think this is a depressing book. What is strange is that it is written in a light, comic tone, and can only be described as uplifting. For example, right near the beginning, speaking of her husband’s aunt, we suddenly get onto:

She even like my newts, and sometimes when we went to dinner there I took Great Warty in my pocket; he didn’t mind being carried about, and while I had dinner I gave him a swim in the water jug.

Her what? Her newts? Or try this:

The book does not seem to be growing very large although I have got to Chapter Nine. I think this is partly because there isn’t any conversation. I could fill pages like this:

“I am sure it is true,” said Phyllida.

“I cannot agree with you,” answered Norman.

“Oh, but I know I am right,” she replied.

. . That is the kind of stuff that appears in real people’s books. I know this will never be a real book that business men in trains will read. . . . I wish I knew more about words. Also I wish so much I had learnt my lessons at school. I never did, and have found this such a disadvantage ever since. All the same, I am going on writing this book even if business men scorn it.

I looked up the author afterwards and found the book was indeed quite autobiographical. What filled me with huge joy was to find that her husband does not even have a Wikipedia page. HAHAHAHAHAHAHAH. All that selfishness (sacrifice?) and apparently for nothing.

I am also really inspired by Comyns biography. It said she “worked in an advertising agency, a typewriter bureau, dealt in old cars and antique furniture, bred poodles, converted and let flats, and exhibited pictures.” It makes other author bios, involving lists of novels/essays/teaching posts seem maybe more ‘successful’ but somehow rather narrow and sad.