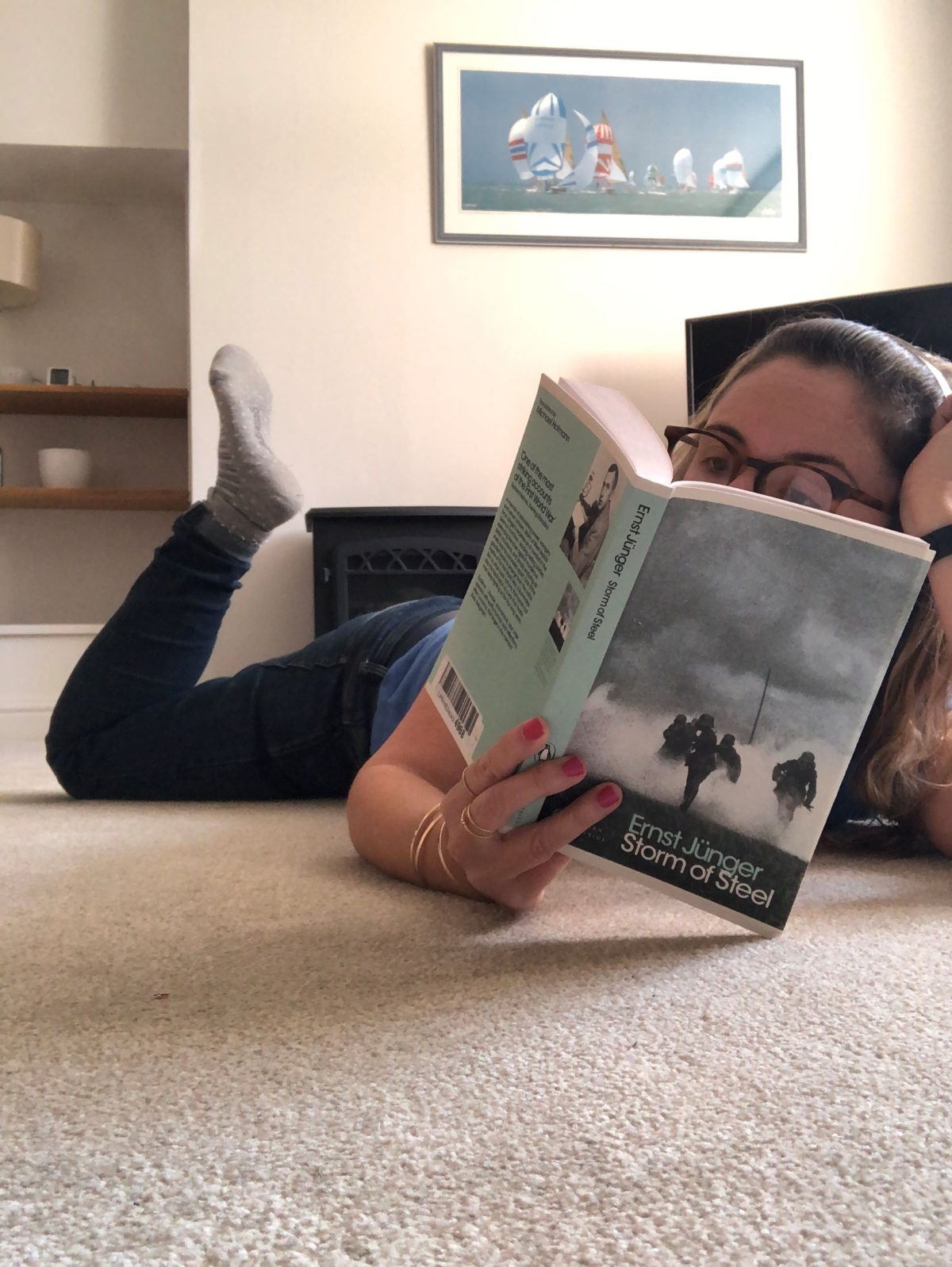

Here is a book about how bad things can get. It’s the dairies of a man who signed up on the the day the first world war began, and, incredibly, made it all the way through to 1918. The Somme, Ypres, Cambrai: he saw them all.

The book was published in 1919, and it shows. Most of the other books of this period were written at a remove of at least a decade or so, but in this one there has been no time to make sense of the war, or to do anything but just tell us what happened. It is in parts boring, as war is boring, and in other parts horrifying. As far as I can tell, no one whom he personally knew with whom he began the war ended it alive with him.

It is deeply revolting. Here he is on a patch of land that has been fought over repeatedly:

In among the living defenders lay the dead. When we dug foxholes, we realized that there were stacked in layers. One company after another, pressed together in the drumfire, had been mown down, then the bodies had been buried under the showers of earth sent up by shells, and then the relief company had taken their predecessors’ place. And now it was our turn.

He is on the German side, and is, as ever, extraordinarily depressing to see how very similar their war was from their alleged ‘enemies’ on the other side. He is even reading TRISTAM SHANDY in the trenches. Towards the end, though, his war does differ from that of English accounts I have read, because he is of course, losing, and he knows it. They start to run out of food; they are no longer sleeping in trenches, but in craters; and still he goes on.

With every attack, the enemy came onward with more powerful means; his blows were swifter and more devastating. Everyone knew we could no longer win. But we would stand firm.

He is clearly losing it.

A profound reorientation, a reaction to so much time spent so intensely, on the edge. The seasons followed one another, it was winter and then it was summer again, but it was still war. I felt I had got tired, and used to the aspect of war, but it was from familiarity that I observed what was in front of me in a new and subdued light. Things were less dazzlingly distinct. And I felt the purpose with which I had gone out to fight had been used up and no longer held. The war posed new, deeper puzzles. It was a strange time altogether.

It is in this context that he goes into his last battle. His company takes a direct hit, and twenty some young men are killed right next to him. Then he goes on for hours, fighting, sobbing, singing. At one point he takes off his coat, and keeps shouting “Now Lieutenant Junger’s throwing off his coat” which had the “fusiliers laughing, as if it had been the funniest thing they’d ever heard.” He cannot remember large stretches of this last battle. At one point he stops to shoot an Englishman, who reaches into his pocket and instead of bringing out a pistol brings out a picture of family. Junger lets him live. He kills plenty of others though, including one very young man:

I forced myself to look closely at him. It wasn’t a case of ‘you or me’ any more. I often thought back on him; and more with the passing of the years. The state, which relieves us of our responsibility, cannot take away our remorse; and we must exercise it. Sorrow, regret, pursued me deep into my dreams

And all this while HE KNOWS THEY CANNOT WIN. Guys, I would have deserted long before, and I am not even ashamed to say it. Honour, like courage, are concepts generally deployed by rich people to get you to do what they want. I can’t think of almost anything for which I would die.