This book is about a pair of middle-aged spinsters living in an English village. It’s a sad, wise novel about the kind of small fantasies we need to keep ourselves going, especially when life has not turned out as we hoped.

Bizarrely, it turns out the author was just twenty-one when she wrote it. Apparently it progress forward her, and her sister, thirty years in the future. Their various university boyfriends also appear, older, fatter, and having rejected them.

The title is based on a poem by Thomas Haynes Bayly:

Some tame gazelle, or some gentle dove:

Something to love, oh, something to love!

One sister is still mooning over the local ArchDeacon, who decided to marry someone else decades ago; the other is always developing crushes on much younger curates, who are continually disappointing her by leaving to evangelize the Africans. Here are the kind of concerns, on knitting for the ArchDeacon:

When we grow older we lack the fine courage of youth, and even an ordinary task like making a pullover for somebody we love or used to love seems too dangerous to be undertaken. Then (the wife) might get to hear of it; that was something else to be considered. Her long, thin fingers might pick at it critically and detect a mistake in the ribbing at the Vee neck; there was often some difficultly there. . . . And then the pullover might be too small, or the neck opening too tight, so that he wouldn’t be able to get his heard through it. Belinda went hot and cold, imagining her humiliation.

Curiously though, both women do receive proposals over the course of the book, and both turn them down; there is an unacknowledged but clear view that in fact, if they could but see it, they are happy as they are, with their gardens and their puddings and their choice of corsetry.

It’s a very delicate little book, almost entirely about women, and domestic matters. I’m amazed, patriarchy being what it is, that it ever got published, because on the surface the concerns it embraces could not be smaller. The point being I guess that life is made up, mostly, of small concerns. And you have to find a way to live it anyway.

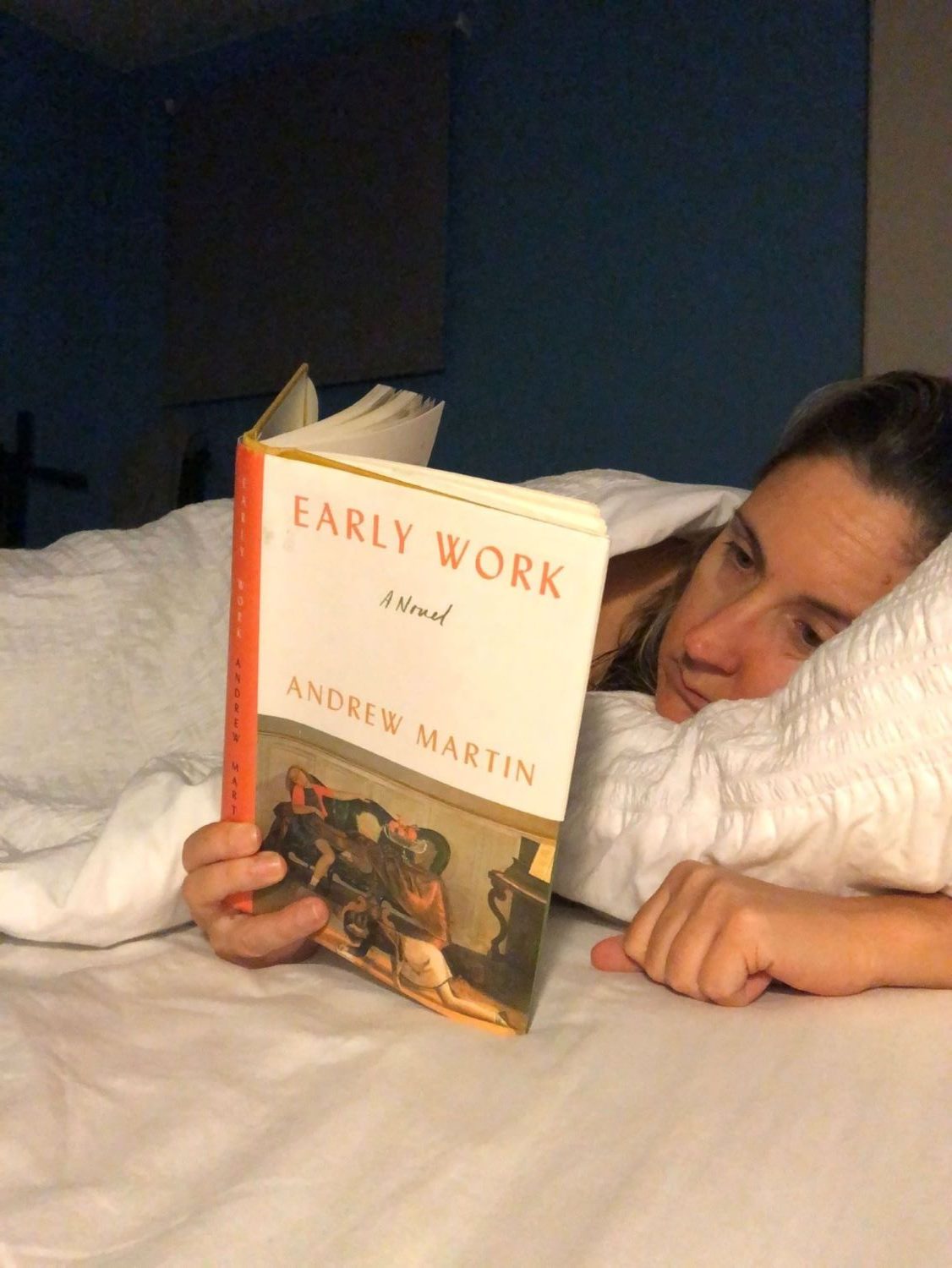

On the picture, by the way: it’s my first audio book!