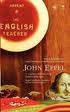

I found this a very touching little novel.

It begins like this: “When George J George mistook his white Ford Escort for the moon, he knew that his time was up. He would turn his face to the evening star and, guided by the nests of whitebrowed sparrow-weavers, keep walking.”

This actually gives you quite a neat little sense of the novel; it’s absurdity, it’s sweetly comic nature, and the way it combines urban and rural, or old and new, Zimbabwe.

Mr George is an English teacher at a private school in Bulawayo. He has started drinking, and is eventually fired when a school boy prank means he hangs a portrait of Ian Smith up where a portrait of Mugabe should be, right before a government visit. His problems only really begin however when he backs his uninsured old car into the spanking new 4×4 of a government minister’s mistress. He cannot pay for the damage, and so in a surreal turn of events the mistress, Beauticious, is able to take possession of his house, and he becomes her domestic servant. He is occasionally arrested, when the police chief needs a free English lesson, and becomes weaker and weaker – the implication is he has some kind of cancer of the colon. A small, silent child is abandoned outside the house, and he cares for her. He is able to deduce where she comes from, and determines to walk her back there. He burns all his identity documents and sets off with the child, using his deep knowledge of and love for the bush to guide him. He manages to return the child, and takes himself off to the bush fort where his grandmother was born, to die.

Here’s the last lines: “By the time he arrived at Fort Mangwe he was literally crawling on his bloodied hands and knees. The ruin was surrounded by whispering grass. He managed to climb over the low stone wall into what remained of the enclosure where his grandmother had been born, and there he died. George had done his duty.”

This makes ABSENT sound like a rather dark book, and it’s not. It’s mostly written with a comic edge. Eg. “The verges on either side of the road were teeming with grasses of every variety, testimony to a good rainy season, and a bankrupt municipality.”

This small novel operates on a very lage number of levels. On one level, its a vicious satire on the new economic elite of Zimbabwe: Beauticious and the minister are presented with appalling clarity, with their BMWs they can barely drive, their refusal to return anything they hire, and their sense of entitlement, and on some level the novel could be read as being entirely about the patronage culture.

It could also be read as some kind of arc of the white experience in Africa. The book makes a very confident claim to a coherent white African identity, and let me tell you, that is not something you meet everyday. The passage of his family’s silver into the hands of Beauticious is clearly a metaphor that just keeps on giving. The long trek through the bush that George knows and loves so well, back to his family’s beginnings, is another.

George is constantly giving English lessons, to Beauticious’ children, to the police chief, and the figures of Lear and Hamlet loom large across the story. There is something here about the importance of great books, across all ages and continents, from Europe to Africa. There’s also something about retaining your own sense of meaning in the face of general collapse. In this context, George’s almost suicidal determination to save one small child who he doesn’t even know is curiously touching, and stands as a rebuke to the Zimbabwe he is living in. The last section, where they follow the white-browed sparrow weaver’s nests into the bush and towards her home, is very sweet, and very sad.