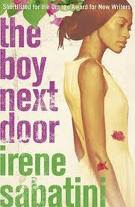

THE BOY NEXT DOOR tells the story of one Lindiwe, who is mixed race (coloured, in Zimbabwean terms), and lives next door to a white boy named Ian. We are first introduced to the pair as teenagers in the 1980s in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe’s second city. Lindiwe is fascinated by Ian, in part because he is suspected of having set his abusive step mother alight, and the 1980s sectin of the novel ends with an aborted attempt by Lindiwe to run away with Ian to South Africa. We move forward some years to find Lindiwe at University. Ian re-enters her life and she is once again fascinated by him. We discover that she became pregnant by him on their trip to South Africa and, keeping it a secret from him, left the baby with her mother. Ian and she become a couple, and take that young boy back. We follow the ups and downs of their relationship, and the growth of their child, into the late 90s.

This book is very successful in recreating the Zimbabwe of the 1990s. This is a period that I actually remember, so it is something I can speak of with confidence. It is however a very 80s kind of 90s, if you know what I mean. Which perhaps you don’t. What I mean is this book begins in the 1980s, and the war and the Gukurahundi cast a very long shadow over the book as a whole. This gives the book very much the feel of a book of the older generation. It joins Mukiwa, say, as book for people older than me. I’ve long noticed that Zimbabweans are divided into those that remember the war, and those that don’t. Most books are written for and about people that do, and suggest that the war is the defining episode of Zimbabwean history.

In THE BOY NEXT DOOR we don’t go forward past 2000, and into the real Zimbabwean apocalypse. Perhaps because Ms Sabatini had already moved to Switzerland, where she now lives, by that time. For people of my generation, the collapse is of course the defining event.

As I mentioned previously in this blog, I went to a talk by another contemporary Zimbabwen author, Bryony Rheam, who felt that one reason she was finding it hard to be published internationally was the fact that publishers abroad wanted a story that ticked the boxes of political and social comment they expect from Zimbabweans – as if people are not leading private lives in collapsing countries! Ms Sabatini manages to tick boxes left and right.

So, I felt the Zimbabwean scene was well evoked, and the story fairly compelling – the surprise of a child, and the attempt to find a way to live together, all made me want to keep reading. The central mystery, of who set the stepmother alight, is never terribly interesting nor is it neatly resolved, and there’s a very unfortunately dubious attempt to get parents’ involvement in the war (yawn) to run as theme defining childrens’ lives in the present. Here’s an excellent, accurate review in the Independent. I wish theatre reviewers would be half as helpful.