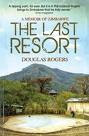

This book tells the story of the author’s parents’ attempts to hold on to their land during the decade of Zimbabwe’s collapse from about 2000 on. The perspective is surprisingly honest: Douglas Rogers couldn’t wait to shake the dust of Africa from his feet, and can’t understand why his parents would fight to stay.

Rogers grew up on various farms in eastern Zimbabwe, and once he left school fled this rural idyll as fast as he could. On retirement, his parents bought a rocky piece of land and decided to run a backpackers lodge, which did well initially, until the economy, and thus the tourism industry, began to crumble.

That Rogers worked as a journalist for many years is abundantly clear from this book. The style is simple and unaffected, and the plot moves quickly enough to keep the attention of any commuter. This is almost to a fault; the book is sort of forgettable, though the story is not.

After the backpackers left, the prostitutes started arriving, then a small dagga business (that’s pot to the non-African readers), then the dispossessed farmers (both black and white), then the illegal diamond dealers, then, most dangerously, the MDC activists in hiding during the dark days of 2008 (that’s during the bloody elections, non-Zimbabwean readers). Meanwhile the possibility of their land being seized was constantly in the air; at one point they found out that their property deed had been cancelled, and ‘vested in the president,’ without their even being informed.

It’s a very intimate portrait of his parents, and of their struggle to maintain not just their lives (it gets very dodgy at the end), and their land, but their definition of themselves as Zimbabwean. In the final chapters, when the father is taking considerable risks protecting the MDC members, there’s a very sweet section about how, for the first time in his life, and for the first time in the history of his family in Africa (an impressive 350 years) he is at last on the right side of history.

This books sounds quite tragic, but is largely written in the comic vein, which is I think very Zimbabwean. It also a story more of victory, than of defeat. I hope that’s very Zim too, though possibly not.

Here’s a rather sweet interview with the author.