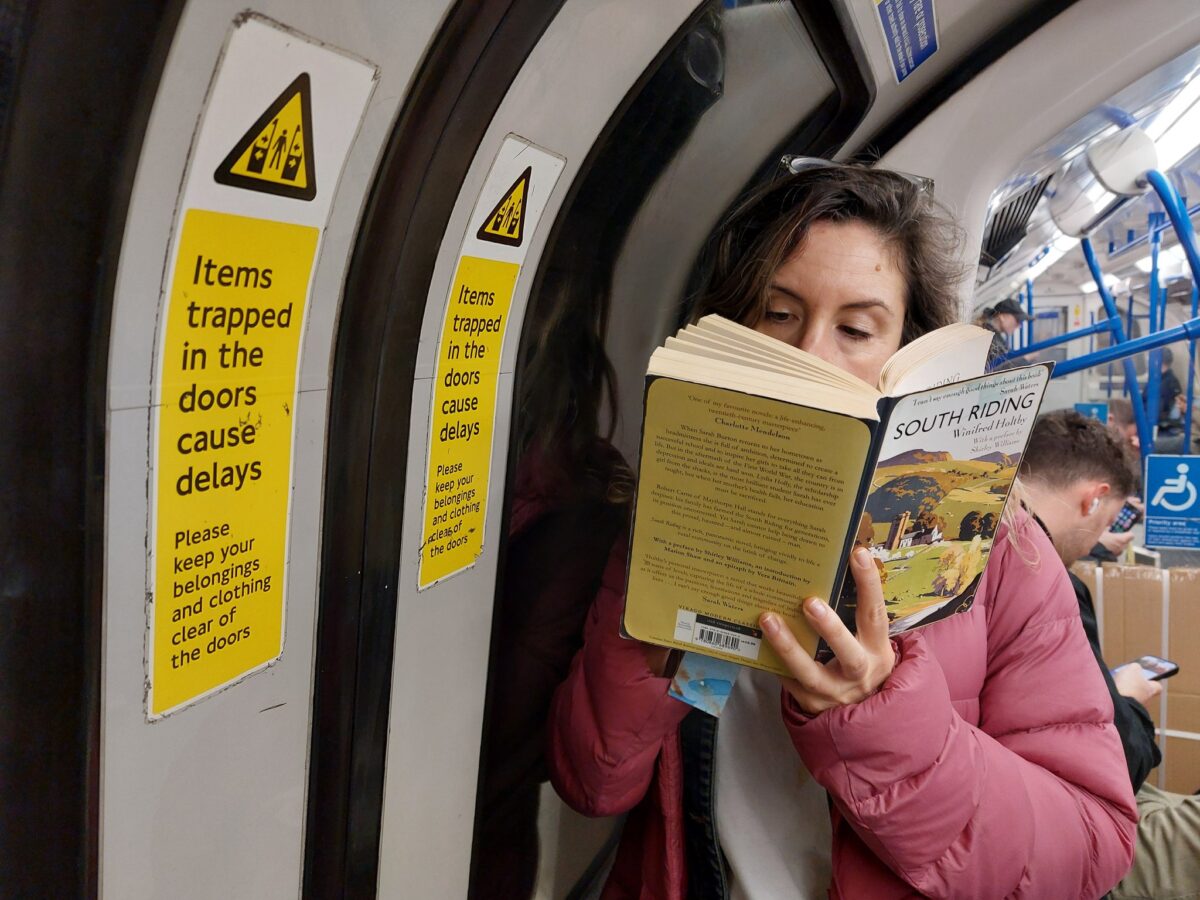

I am always struck by how vanishingly rare it is to read a book by a working class person before about 1950. Here is one. It’s a hair raising account of heavy boozing and factory work in Nottingham, and you know all you need to know when I tell you this book is where the expression ‘Don’t let the bastards get you down’ comes from. Try this sample:

“Factories sweat you to death, labour exchanges talk you to death, insurance and income tax offices milk money from your wage packets and rob you to death. And if you’re still left with a tiny bit of life in your guts after all this boggering about, the army calls you up and you get shot to death. . . . Ay, by God, it’s a hard life if you don’t weaken, if you don’t stop that bastard government from grinding your face in the muck, though there ain’t much you can do about it unless you start making dynamite to blow their four-eyed clocks to bits.”

‘It’s a hard life if you don’t weaken!’ I love that

This author began life as a factory worker, but then married a poet and used his army pension to move to Spain to write. I was touched to hear he wrote this under a lemon tree at Robert Graves’ house, who was the person who encouraged him to write the life he knew. I love Graves’ GOODBYE TO ALL THAT, a wonderful book about binning your life and becoming a bohemian, and it was sweet to meet him at second-hand through this other writer.