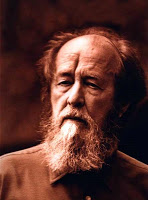

This book has taken me months to read. This is not because it is boring, but because it is so sad it is hard to keep going. It is sad like real life is sad, because the sadness has no rhyme or reason or moral. If you didn’t read my earlier post, GULAG ARCHIPELAGO tells the story of the death camps that existed in Stalinist Russia from the 1930s onwards, and is written by a man who survived them. Obviously, the state was not keeping good records of what was going on – indeed, they were trying to cover it up – and most free people did not know what the camps were like. Solzhenitsyn clearly strongly felt that all the people he met should not have died entirely unmourned and in vain, so he set to record as much of it as he could, based on the people he himself met, and those others met.

The cover has a quote from the Preface “For years I have with reluctant heart withheld from publication this already completed book: my obligations to those still living outweighed my obligation to the dead. But now that State Security has seized the book anyway, I have no alternative but to publish it immediately.” It got seized because a woman he entrusted part of the manuscript to broke down after A HUNDRED AND TWENTY HOURS of interrogation without sleep, and revealed its location, and the poor woman was so distressed by the betrayal that she killed herself.

What’s perhaps saddest about the book is the way in which he’s clearly writing about events that are so current. He gives lots of tips about how to survive prison – like practical stuff about surviving the thirst when they feed you only very salty fish and a half mug of water a day, and about how you must give away anything of value right away, as a man who has something to lose is a man who fears, and that’s lethal – really sort of awful grim advice – and it’s clear he’s doing this because many of the people reading will be going to prison themselves.

Guess how many people were in the Gulag at any time? Answers on a postcard. Oh, okay, I’ll just tell you. SIX TO TWELVE MILLION. And this is not prison, this is death camps. Often, you’d spend a month in a transport, with a hundred people in a railcar meant for twenty, and corpses thrown out at every stop (this is when you get the fish and water and nothing else), and when you get to the end of the line in Siberia, there is nothing there. Nothing at all. You are just going to build the camp right there. But it’s -30C, so you can’t dig into the ground, you just lie under tarpaulins in thin clothes (the guards steal all your warm clothes) and are sent to work everyday. And all you get to eat is fish, and just flour, that you wash down with SNOW. So obviously, almost everybody dies.

The authorities know that the public are aware that there are a lot of arrests, but they want to keep the full scale secret, so when it comes time to transport prisoners – one example given is a thousand a day, from one medium size town – they move them all at night. The government fears there’d be an outcry if the public are able to grasp the full breadth of the arrests. They used to write ‘Meat’ or ‘Bread’ on the cars(of which there wasnt much of either) so people would even be encouraged by thinking there was food in the country. One of the saddest parts of the book is when he tells you all about how once when they were changing trains, he and the others were hidden between two cars, and they got to listen to music from a nearby bar, and hear people laughing, and how they were all so incredibly happy. He goes on and on about this, like it was a highlight, and it was only twenty minutes.

In one cell, before going to the death camp, there were a lot of scientists. The reason for this is lots of intelligensia got sent to death camps authomatically, because they were bourgeoisie traitors etc. But once the government got rid of all the scientists, they realised: fuck, we don’t have any scientists. So they called them all back. Our man Solzhenitsyn only lived to tell the tale because on his prison card for occupation he wrote ‘nuclear phyisist.’ And their records were so bad, they believed him. Their records were so bad they often didn’t know if you were supposed to serve 10 or 25 years, so they just kept you for 25 years on general prinicples. I mean obviously only if you actually managed to live that long. Anyway, so in this cell, they used to have ‘Cell 72 Scientific Society’ that met every day after morning bread ration by the left window. Can you imagine?

Just the only last thing that really killed me, is that lots of people in the cells were WWII veterans. Can you imagine making it through the war to end up in a death camp? Our author was one. And he tells such grim stories about the war – how once he saw a Russian whipping a German who he had roped up to his carriage, like a horse. And he tells us how he did nothing about it. Solzhenitsyn feels that prison purifies, which is interesting. Lots and lots of people went insane, but if you don’t, he says you are purified. When he gets out, he honestly can’t grasp where other peoples’ problems are coming from. He says ‘What about the main thing in life, all its riddles? If you want, I’ll spell it out for you right now. Do no pursue what is illusory – property and position: all that is gained at the expesne of your nerves decade after decade, and is confiscated in one fell night. Live with a steady superiority over life – don’t be afraid of misfortune, and do not yearn after happiness; it is, after all, all the same: the bitter doesn’t last forever, and the sweet never fills the cup to overflowing. It is enough if you don’t freeze in the cold and if thirst and hunger don’t claw at your insides. If you back isn’t broken, if your feet can walk, if both arms can bend, if both eyes see,and if both ears hear, then whom should you envy? And why? Our envy of others devours us most of all.’ And I try and hear him, because you get the very clear idea that he’s walked a long hard road to get somewhere.