I had to read this one for work.

Blah blah child murder blah blah terse court room scenes blah blah divorced detective.

Can you believe this thing is a bestseller? And worse yet, like tenth in a series of bestsellers. Is everyone morons?

I had to read this one for work.

Blah blah child murder blah blah terse court room scenes blah blah divorced detective.

Can you believe this thing is a bestseller? And worse yet, like tenth in a series of bestsellers. Is everyone morons?

This one won the Booker this year. It got quite famous as far as literary novels get famous. The sides of buses carried adverts for it saying ‘Stop talking about it and start reading it’ which I thought was quite funny. So anyway, I’ve read it. It’s about an assistant of Cardinal Wolsey’s, called Thomas Cromwell, who, after Wolsey’s fall from grace, takes over as a helper to Henry VIII in his attempts to ditch Katherine for Anne Boleyn.

On the one hand, it was kind of a ye-olde-strong-on-the-plot historical novel; on the other, it was kind of literary. The plot part told how Thomas Cromwell was a blacksmith’s son who ran away to fight in wars on the continent. He got all tough and brilliant and spoke a ton of languages and got very close to the king. This was kind of fun front seat of history stuff, it was interesting how they loved to eat thin sliced apples in cinnamon, and how people dropped dead of various diseases left and right. I found it a bit dubious that everyone was supposed to be terrified of our hero, but then he was as written totally sympathetic. But the literary-ish stuff was lovely. Here’s a good bit – mid historical drama, it’s suddenly: “He stares down into the water, now brown, now clear as the light catches it, but always moving; the fish in its depths, the weeds, the drowned men with bony hands swimming.” It’s also kind of a love letter to London, in the way she writes about it.

One thing I found very weird was that it’s called WOLF HALL, right, but we never get to freaking Wolf Hall. It’s mentioned, but it’s not even important. Not even metaphorically. Not so far as I can tell. Maybe I’m missing something.

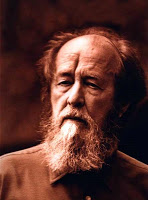

This book has taken me months to read. This is not because it is boring, but because it is so sad it is hard to keep going. It is sad like real life is sad, because the sadness has no rhyme or reason or moral. If you didn’t read my earlier post, GULAG ARCHIPELAGO tells the story of the death camps that existed in Stalinist Russia from the 1930s onwards, and is written by a man who survived them. Obviously, the state was not keeping good records of what was going on – indeed, they were trying to cover it up – and most free people did not know what the camps were like. Solzhenitsyn clearly strongly felt that all the people he met should not have died entirely unmourned and in vain, so he set to record as much of it as he could, based on the people he himself met, and those others met.

The cover has a quote from the Preface “For years I have with reluctant heart withheld from publication this already completed book: my obligations to those still living outweighed my obligation to the dead. But now that State Security has seized the book anyway, I have no alternative but to publish it immediately.” It got seized because a woman he entrusted part of the manuscript to broke down after A HUNDRED AND TWENTY HOURS of interrogation without sleep, and revealed its location, and the poor woman was so distressed by the betrayal that she killed herself.

What’s perhaps saddest about the book is the way in which he’s clearly writing about events that are so current. He gives lots of tips about how to survive prison – like practical stuff about surviving the thirst when they feed you only very salty fish and a half mug of water a day, and about how you must give away anything of value right away, as a man who has something to lose is a man who fears, and that’s lethal – really sort of awful grim advice – and it’s clear he’s doing this because many of the people reading will be going to prison themselves.

Guess how many people were in the Gulag at any time? Answers on a postcard. Oh, okay, I’ll just tell you. SIX TO TWELVE MILLION. And this is not prison, this is death camps. Often, you’d spend a month in a transport, with a hundred people in a railcar meant for twenty, and corpses thrown out at every stop (this is when you get the fish and water and nothing else), and when you get to the end of the line in Siberia, there is nothing there. Nothing at all. You are just going to build the camp right there. But it’s -30C, so you can’t dig into the ground, you just lie under tarpaulins in thin clothes (the guards steal all your warm clothes) and are sent to work everyday. And all you get to eat is fish, and just flour, that you wash down with SNOW. So obviously, almost everybody dies.

The authorities know that the public are aware that there are a lot of arrests, but they want to keep the full scale secret, so when it comes time to transport prisoners – one example given is a thousand a day, from one medium size town – they move them all at night. The government fears there’d be an outcry if the public are able to grasp the full breadth of the arrests. They used to write ‘Meat’ or ‘Bread’ on the cars(of which there wasnt much of either) so people would even be encouraged by thinking there was food in the country. One of the saddest parts of the book is when he tells you all about how once when they were changing trains, he and the others were hidden between two cars, and they got to listen to music from a nearby bar, and hear people laughing, and how they were all so incredibly happy. He goes on and on about this, like it was a highlight, and it was only twenty minutes.

In one cell, before going to the death camp, there were a lot of scientists. The reason for this is lots of intelligensia got sent to death camps authomatically, because they were bourgeoisie traitors etc. But once the government got rid of all the scientists, they realised: fuck, we don’t have any scientists. So they called them all back. Our man Solzhenitsyn only lived to tell the tale because on his prison card for occupation he wrote ‘nuclear phyisist.’ And their records were so bad, they believed him. Their records were so bad they often didn’t know if you were supposed to serve 10 or 25 years, so they just kept you for 25 years on general prinicples. I mean obviously only if you actually managed to live that long. Anyway, so in this cell, they used to have ‘Cell 72 Scientific Society’ that met every day after morning bread ration by the left window. Can you imagine?

Just the only last thing that really killed me, is that lots of people in the cells were WWII veterans. Can you imagine making it through the war to end up in a death camp? Our author was one. And he tells such grim stories about the war – how once he saw a Russian whipping a German who he had roped up to his carriage, like a horse. And he tells us how he did nothing about it. Solzhenitsyn feels that prison purifies, which is interesting. Lots and lots of people went insane, but if you don’t, he says you are purified. When he gets out, he honestly can’t grasp where other peoples’ problems are coming from. He says ‘What about the main thing in life, all its riddles? If you want, I’ll spell it out for you right now. Do no pursue what is illusory – property and position: all that is gained at the expesne of your nerves decade after decade, and is confiscated in one fell night. Live with a steady superiority over life – don’t be afraid of misfortune, and do not yearn after happiness; it is, after all, all the same: the bitter doesn’t last forever, and the sweet never fills the cup to overflowing. It is enough if you don’t freeze in the cold and if thirst and hunger don’t claw at your insides. If you back isn’t broken, if your feet can walk, if both arms can bend, if both eyes see,and if both ears hear, then whom should you envy? And why? Our envy of others devours us most of all.’ And I try and hear him, because you get the very clear idea that he’s walked a long hard road to get somewhere.

Honestly, massive props to gutenberg.net. I don’t know how anyone gets through their workday without it. DR THORNE has been keeping me company many a long day. Here’s where I first blogged about it ages ago, and I’ve finally finished it. I ran out of stuff to read on the train, so I finished it on the tiny screen of my mobile, to the not very Victorian, but very tinny, music coming from some moron’s i-pod.

The props go direct to the guy in the picture, who dreamed Gutenberg up in 1971.

DR THORNE tells the story of a young lady, neice of Dr Thorne, who is illegitimate and poor. A young man of good family falls in love with her, but obviously his whole family opposes the romance, as his estate is in debt because of his father’s extravagance, and he ought to marry money. Surprise, surprise, Mary is found to be a heiress and all ends happily.

This sounds thoroughly lame, but the charm of the book lies not in its plot. It’s the warmth of the narrator’s voice – if you’ve lived in England, you can’t help but love “Let no man boast himself that he has got through the perils of winter till at least the seventh of May.” It’s also the loving way the characters are presented. Note that the book is called Dr Thorne, but not because the story if about him, or because he’s the narrator, but just because Trollope likes him. That’s the kind of book it is.

Here it is. I recommend beginning immediately.

I am off to Zimbabwe for three months, so I’ve ordered a ton of books. DR THORNE is the third of the Barchester novels (I’ve also read the first two) and please don’t doubt I’ve ordered the remaining three. It will be very Victorian, as Zim has non-stop power cuts at the minute so I am sure I will read a lot of them by candlelight . . .