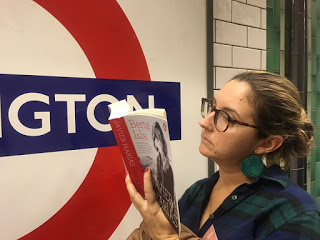

I read this book on holiday on a tropical island, and woke up the person I was sleeping with by quietly blubbling over it at 1 o’clock in the morning. It is not a book about which it my business to say if it was ‘good’ or ‘bad’ but rather just to be astonished at what this man has achieved. What he has achieved is surviving forty years in solitary confinement with his sanity intact.

Woodfox was born to a poor and unmarried woman in the 1940s in New Orleans. She sometimes had to prostitute herself to keep them fed. Woodfox was picked up by police many times, often not for crimes but just to meet arrest targets (apparently this was very common in the mid twentieth century). Eventually for a car theft (that he did in fact do) he is offered either four years in a medium security prison or two years in the maximum security prison of Angola. Being young and dumb he takes Angola. As he puts it:

The horrors of the prison in 1965 cannot be exaggerated.

And this is a man who has seen more than most of us. Here he describes ‘fresh fish’ day, where new prisoners walk to their dormitories.

It was also the day sexual predators lined up and looked for their next victims. Sexual slavery was the culture at Angola. . . . If you were raped at Angola, or what was called ‘turned out,’ your life in prison was virtually over. You became a ‘gal-boy,’ . . . you’d be sold, pimped, used, and abused by your rapist and even some gaurds. Your only way out was to kill yourself or kill your rapist.

If the latter, you were free from further rape, but would never leave prison. He tells us of his entrance there in 1965:

26 of us went down the walk that day. T.Ratty and I were the only two who didn’t get turned out.

Angola used to be a slave plantation, and was still run on similar lines, with white guards (called not guards but ‘freemen’) living on site and the job being passed down from father to son. Prisoners were forced to work in the fields for 2 cents an hour without proper safety gear. At some point Woodfox is transferred to a different jail, and there he meets some inmates who are Black Panthers. His life and his worldview are transformed by exposure to their political philosophy. Barely literate before, he learns for the first time of colonialism, of great African-Americans, and of the idea that his mother’s tough life was a result of systemic oppression rather than her personal failings. He pledges his life to the ‘ten principles’ of the Black Panthers, and when he is transferred back to Angola single-handedly begins to try and re-educate his fellow inmates. He now sees himself as a political prisoner working for the greater good. He understands that prison operates by keeping inmates separated, and ill-educated, and works to unify them around certain causes (e.g., no more anal cavity searches), and to end the rape culture that destroys so many inmates mentally. He meets two other prisoners, Herman and King, who are also Panthers, and the three begin a lifelong relationship that goes beyond friendship to a kind of solidarity we who are free will be lucky to ever achieve.

When a white prison guard is murdered, the three are framed for it, as the guards have noticed their power with the inmates. So slapdash is the framing, that King was not even at the prison when the guard was killed. Three inmates testify against them (and are then given much reduced sentences). Incredibly, ten inmates, despite beatings and time in ‘the dungeon’ (you don’t’ want to know), testify for them. It doesn’t matter, as the all white jury are all closely connected to Angola prison staff , and so the three begin their time in solitary. This is 23 hours a day in a cell the size of a walk-in closet. Only in the late seventies are they allowed out in the open air for their one hour a day; at that time, some prisoners haven’t been outdoor in DECADES. Prisoners frequently lose their minds. Most are taken off CRR (as its called) after a few months, but these three despite blameless records remain there as the years pass.

They are tear gassed so often they get used to it, and don’t need masks while the guards do. They are beaten often. But the claustrophobia is clearly the worst. They remain true to their Black Panther ideals, unaware that the Black Panthers have long been disbanded. As old men, Anita Roddick of the Body Shop becomes interested in their case. The State of Lousiana, incredibly, first tries to claim that their conviction is not unsafe, and then that in any case solitary confinement for FORTY YEARS is not cruel. Even has Herman is given just weeks to live due to liver cancer, they still won’t let him out. Woodfox’s lawyer manufactures a way for him to see Herman, but the State says he must wear the ‘box’ on his wrists – which is known to be painful even for an hour. He agrees to do it for fifteen hours so he can see his dying friend.

I didn’t say much. My communication with Herman was mostly silent. I didn’t know how much time he had left. I silently told him how much I loved him, and that when we didn’t have his back anymore, the ancestors would.

Eventually Herman, days from death, is allowed out of prison – but only after the warden is threatened with prison himself. They take him to a hospital so he can at last ‘be free’ and bring in flowers for him to smell, his first in decades. He dictates a death bed statement, avowing his and Woodfox’ innocence.

The state may have stolen my life, but my spirit will continue to struggle along with Albert and the many comrades who have joined us along the way here in the belly of the beast.In 1970 I took an oath to dedicate my life as a servant of the people, and although I ‘m down on my back, I remain at your service.

Woodfox is eventually freed too. He reminds us in closing that Lousiana’s incarceration rate is the worst in the world, at 1 in 86 adults, which 13x China’s and 2x the American average. A two time car burglar can easily receive 24 years. He also reminds us that the system remains institutionally racist, with a black arrestee 75% more likely to get a charge with a minimum sentence than a white one for the same crime

What impressed me most about this book was Woodfox’s victory in the mental struggle, which is the struggle we all face, though those of us lucky enough to be free face a smaller version of it. It is remarkable to see how far he travelled while never leaving his tiny cell.