Among that entire domestic fauna, the only one to have any importance in the collective memory of the family was a rabbit Miguel had once brought home, a poor ordinary rabbit that the dogs had constantly licked until all its hair fell out and it became the only bald member of its species, boasting an iridescent coat that gave it the appearance of a large-eared reptile.

The rabbit is never mentioned again. Also why were the dogs licking it so much? No one knows. The book is full of stuff like this. Someone dies, and here is the response:

“You can bury her now,” I said. “And while you’re at it, I added, you might as well bury my mother-in-law’s head. It’s been gathering dust down in the basement since God knows when.”

I mean: ?

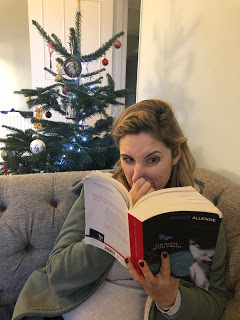

It makes for a strangely absorbing, and very dense book, full of characters and ideas. It covers about a hundred years from the late 1800s up to a unnamed dictator’s rise (i.e., Pinochet). From a Zimbabwean perspective, I note once again how glad I am to have only a relatively inefficient dictatorship. Apparently you can really torture a lot people once you get organized.

It was mostly enjoyable for its lush bizarreness, but I did enjoy this perspective on why it can sometimes be better not to actually get to be with the one you love: