But just as feet know the path, fingers know the keys. Fifty yards from the market place there is no light pollution, no urban backwash to pale the sky; no light path, no footfall. There is starlight, frost on the path, and owls crying from three parishes

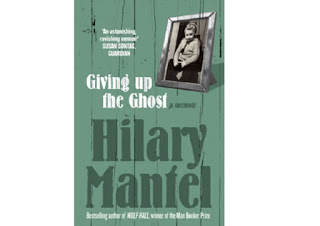

The book has three main focuses: her childhood, her illness, and bizarrely the process of buying her house. She grew up in a working class family, and is one of that group of English writers whose whole life was changed by passing the 11+ exam. It’s all very hard scrabble, especially the part where her mother leaves her husband for another man but they all continue to live together, but not in a cool menage-a-trois kind of way, more in an economic necessity kind of way.

Then she goes to university and gets married, but this is largely summarized in a couple of lines. The main focus is on her illness. She has endometriosis, which is famously an under-diagnosed disease among women. It’s still so today, but back then it was really bad: they sent her to a lunatic asylum rather than believe her symptoms. (I said it was better today, but not a lot better. Ladies: if you have really bad period pain don’t let anyone tell you it’s not really bad).

Now, all that said, let me clarify that I’m not saying she’s not crazy. There are some pretty questionable parts. She was very frightened once when she saw something creepy in the garden when she was eight. It’s not clear what it was, possibly a ghost, possibly just a quality of the light, but she emphasizes repeatedly how frightening this was. I would never tell people about such a thing. I’m just not ready for the mockery. Same with the last memoir, about the aunt who was just too charismatic. I’m beginning to conclude that writing a good memoir means not worrying about mockery.

You come to this place, mid-life. You don’t know how you got here, but suddenly you’re staring fifty in the face. When you turn and look back down the years, you glimpse the ghosts of other lives you might have led. All your houses are haunted by the person you might have been. The wraiths and phantoms creep under your carpets and between the warp and weft of your curtains, they lurk in wardrobes and lie flat under drawer liners.

They were not . . . the sort for adulterous upsets, for drunken fumbles, for spring folie, for subterfuge and lies. They were grounded infotec folk, hardware or software people. . They were mobile in their habits till their children fixed them; keen, pragmatic, willing to defer gratification . . . Men and women met each other halfway, gentle fathers and defined, energetic mothers. . . They had parents, but they had them as weekend accessories, appearing on summer Saturdays like their barbecue forks

Her endometriosis, being treated very late, means she can’t have children, and these almost-children also haunt the book.

Even adulterers have their ghost children. Illicit lovers say: what would our child be like? Then, when they have parted or are forced apart, the child goes on growing up, a shadow, a half-shadow of possibility. The country of the unborn is criss-crossed by the roads not taken, the paths we turned our back on. In a sly state of half-becoming, they lurk in the shadowland of chances missed.