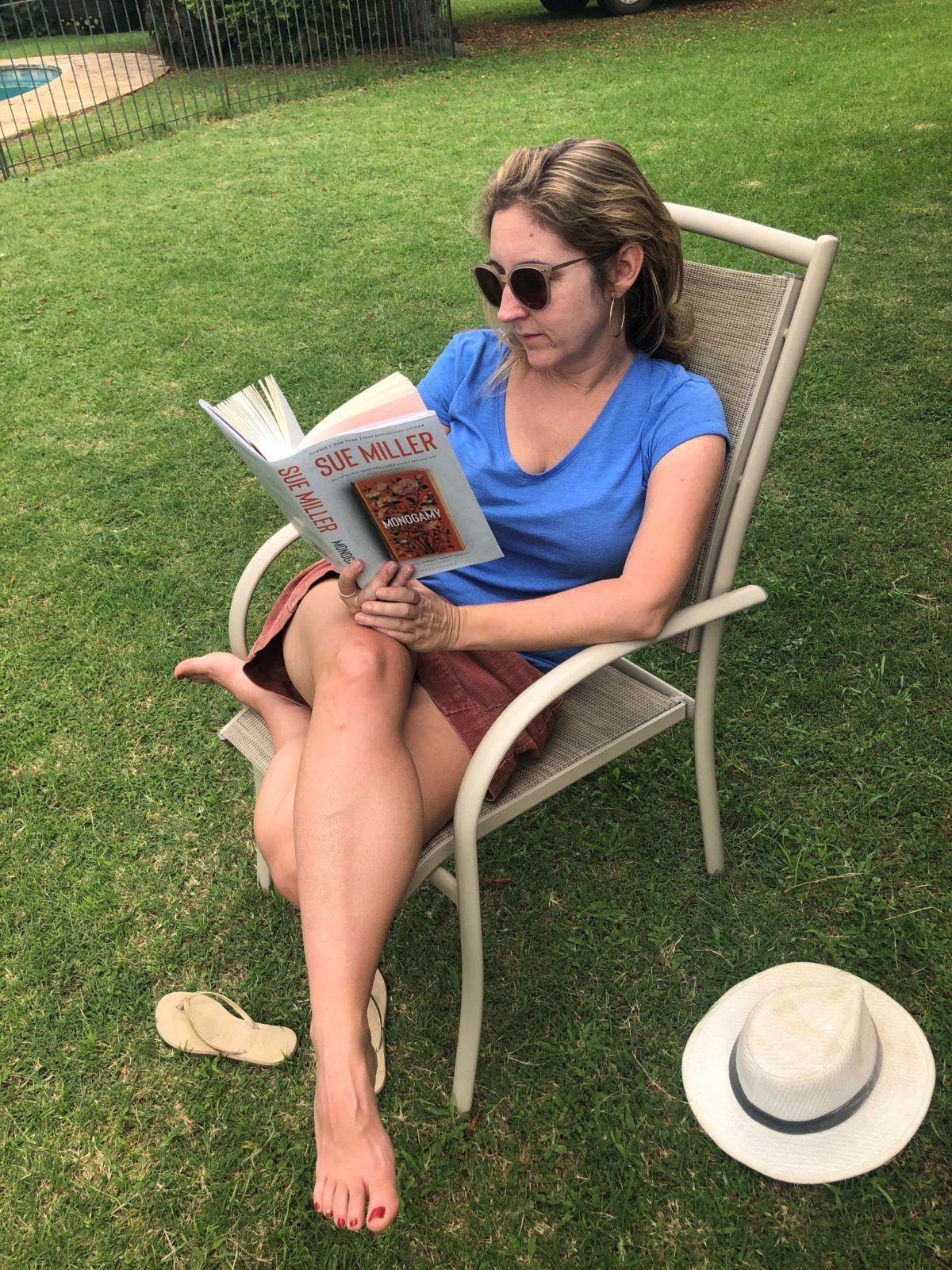

All I have to say to this novel is OK BOOMER.

It tells the story of a marriage between two older people, and about their circle of friends. We learn a lot about their daily lives, their dinner parties, their CD collections. Enjoy this sample:

She had already prepared the white beans with thyme and olive oil for tomorrow’s dinner, and the plan was to put the lamb in a marinade tonight. But she still had some shopping to do – last minute things. Back in Cambridge, she stopped at Formaggio, the fancy neighbourhood shop, for cheeses – cheeses and crackers and several kinds of olives. They had cherry tomatoes that looked nice in the produce section . .

I’m not even going to get into the ‘frisee salad with new potatoes and bacon’ incident.

The husband is a book store manager, the wife a very under-employed photographer. What we don’t learn is how they are funding two homes, and two kids, and daily fancy meals, on those salaries!?! This is the kind of lifestyle you only get to have if you were born in the 1940s or 50s. MONOGAMY was like having my nose rubbed in inter-generational economic unfairness for 336 pages. I already have had quite enough of it from when those selfish people voted Brexit, secure in the knowledge that they would not be the ones working to pay their fat pensions.

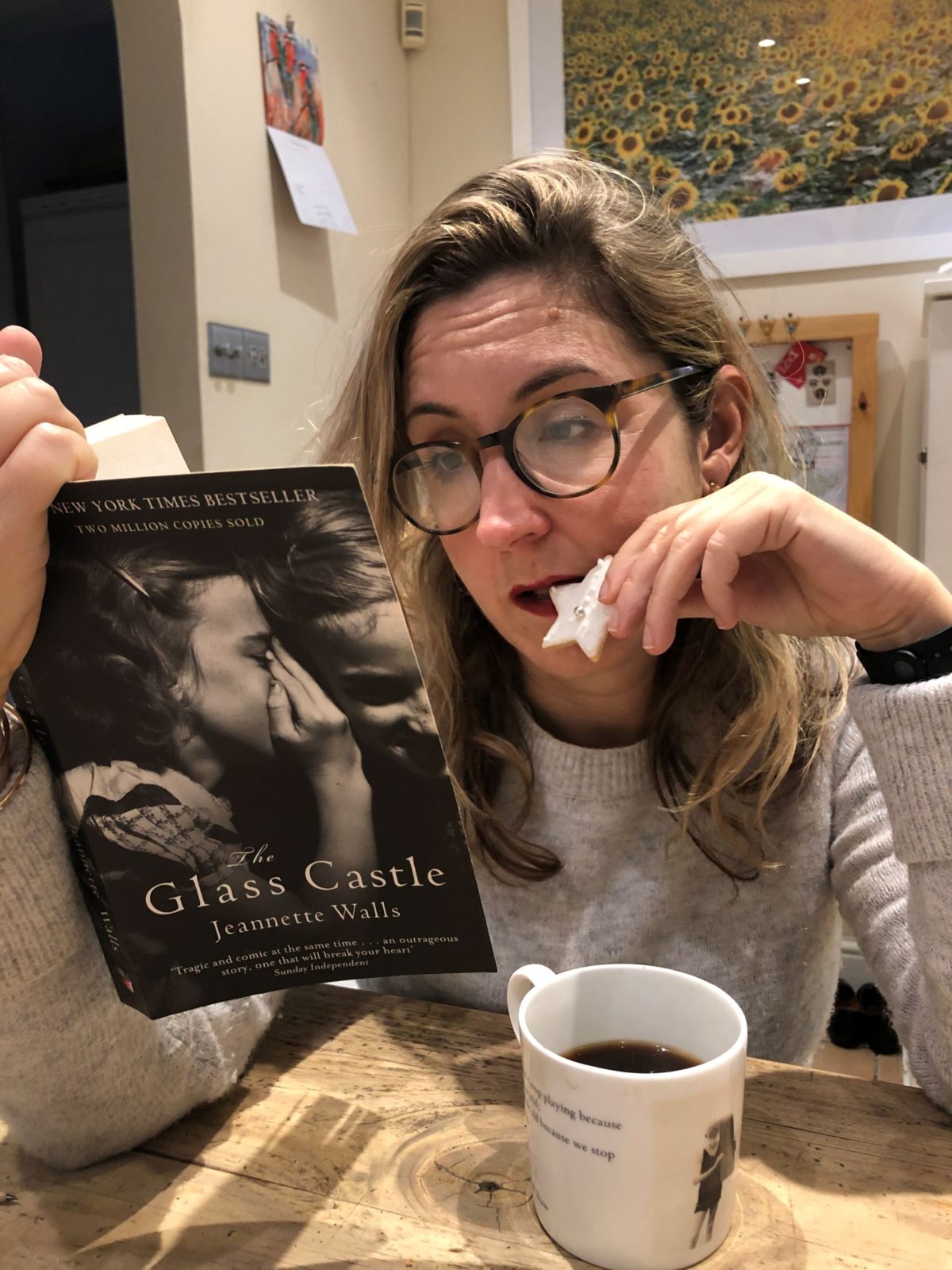

The hook of the book is that after the husband dies the wife finds out he had a brief affair. Rest assured, there is nothing revelatory in this. Everyone acts like they can’t imagine why someone married thirty years might have an affair and yet still love their wife. I mean, snore.

There was only good part, which was where we learn about how the husband gave up on writing a novel:

It had felt liberating to acknowledge this to himself and others, to shed his painful sense of the obligation to be somehow remarkable; but it left him with the unanswered question of what to do with his life, and simultaneously the realization that working on the novel endlessly had been a way to avoid facing that question.

I like the idea of giving up on being remarkable.