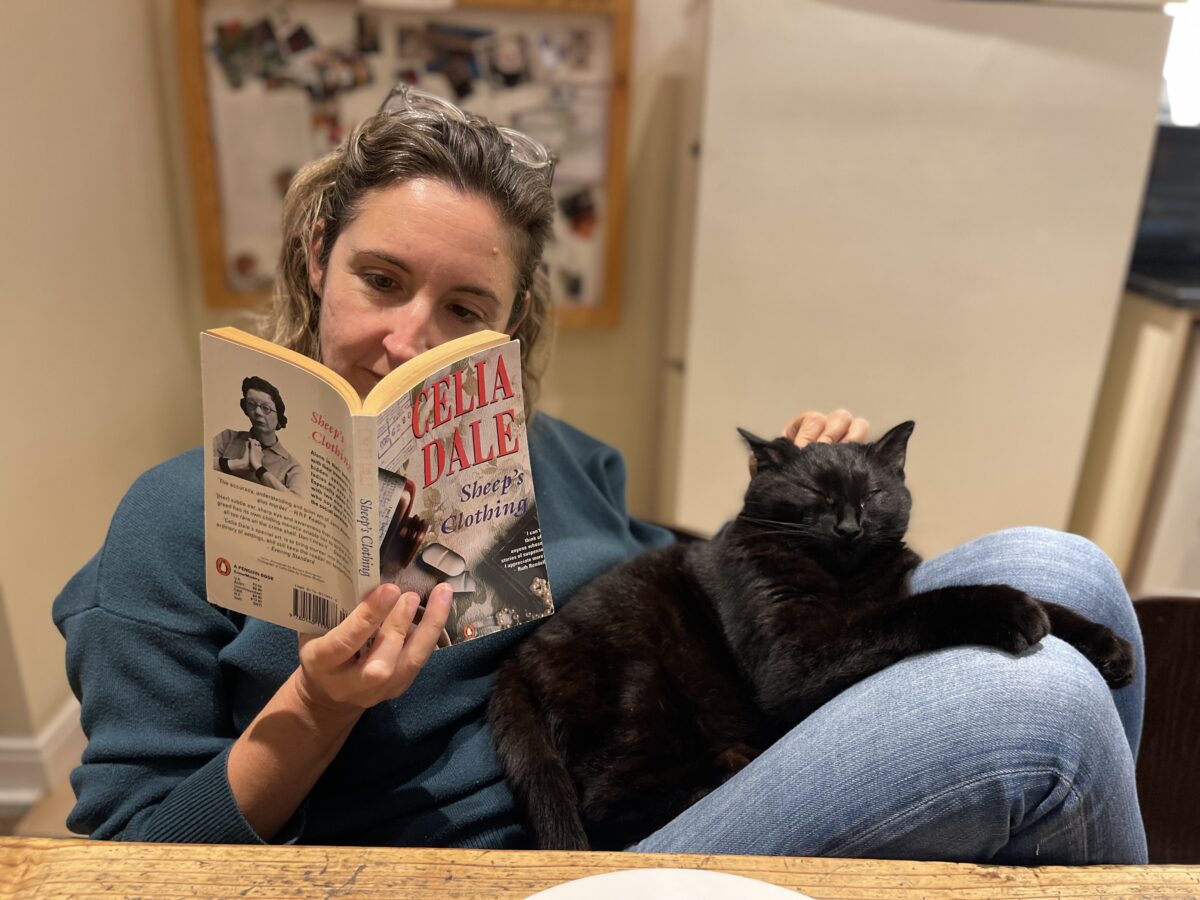

I am a mega-fan of Rooney’s first book, CONVERSATIONS WITH FRIENDS, which is one of the handful of books I have ever read twice in a row. I have been less of a fan of her other books, and especially of the last one BEAUTIFUL WORLD, WHERE ARE YOU? Much of what I enjoyed about the first one was the comic and contemporary spirit, and as we went along I felt we were getting more and more miserable. This one is a return to form. It tells the story a pair of brothers and their various romantic entanglements, and is exceedingly more-ish. I enjoyed it a lot, especially the journey of one character who has to slowly give up his implicit assumption that he is and can be ‘normal,’ which I found to be quite liberating.

My only issue with it was tbh a bit of a political one. In all Rooney’s books there is a strong perspective that anyone who works in any area of commerce is obviously some kind of sad, dead-eyed zombie in slave to our capitalist masters. Apparently the only acceptable professions are like lawyer, journalist, arts administrator. You can work as e.g., a barista, but only if you feel utterly polluted by it. I just find this bizarrely decadent. As if any of these delightful professions would exist without this economic model. Talk about biting the hand that feeds you.