A very compelling story about a young Irish girl who gets pregnant and comes to England to find the father with whom she had a holiday romance. She doesn’t find him, but she does find what we slowly conclude is some kind of SPOILER ALERT serial killer. This makes it sound like it’s cheesy, but it’s really not. Trevor is a really gifted writer and tells the story from both POV in a very compelling way. My main take away is, THANK GOD FOR FEMINISM. This poor girl is so messed up that she really is barely able to advocate for herself in even the most basic ways, and that’s before she meets the serial killer.

Tag: male writer

THE SINGULARITY IS NEARER by Ray Kurzweil

This book is a fantastically named sequel to his first, THE SINGULARITY IS NEAR. The Singularity is moment at which our brains are able to meld with a computer, so we will – according to him – be able to be fantastically more intelligent. A bit like the leap from Neanderthal to today.

It’s a book absolutely bristling with ideas – I highlighted lots of it. Like, for example, do you know the odds of the sperm and egg meeting to make you was 1 in 2 million trillion? And then go back through all the people who had to meet and mate to produce your parents, to see how lucky you are to be alive. Even wilder, he talks about how many things had to go right for life to have emerged on earth at all; apparently it is the same likelihood as a tornado blowing through a junkyard and assembling a Boeing 747.

He has lots of big ideas for the future – for example, for when nanotechnology will be able to print anything, because it will be able to assemble stuff at atom level. So lithium will no longer be precious; nor will diamonds. He believes the world is getting better (did you know deaths from war in prehistory were about 500/100K; now they are 4/100K, even counting nuclear weapons?), and will continue to get better quickly. He makes some good arguments, pointing out how unimaginable landing on the moon was in the early 1900s, when no one had even flown yet.

I struggled a lot with all this talk of the ‘one way march of progress.’ I see what he means, but on the other hand, I’m not sure I do. What about the fall of Rome? What about the dangers of AI? I hate to say it, but all this boundless optimism just said one thing to me, and that one thing was: boomer. I get it, your life has just been one long upward swing. Here’s fingers crossed for the rest of us.

PRIVATE CITIZENS by Tony Tulathimutte

This book is very more-ish and seethes with verbal energy. Try this:

“If you preferred the indoors, everyone assumed you were scared of life and emotionally stunted. That wasn’t it. . . . Sure, it was nice to have some fresh air while he smoked. But he was myopic, hard of hearing, congested – reality was lo-fi, slow and obstructing, too cold or too bright, filled with scrapes, sirens, hidden charges, long distances, pollen, and assholes”

It was also kind of hilarous; one character, we are told, has seen ‘most of’ the porn on the internet. Given that this is set in 2007, what is eerie is I guess this might just conceivably be possible. Today I suppose it would take several lifetimes. The book tells the story of four friends living in San Francisco a couple of years after they graduate from Stanford. About two-thirds of the way through, I started to get exhausted. Everyone was so self-harming! There was anorexia, self hatred based on race, failing to take your anti-psychotics, lying about rape, and that’s just the first few I can think of. And of course there was no redemption: it was just self-harm and self-harm some more. But weirdly I still enjoyed it.

TROUBLES by JG Farrell

This author was kind of a jock at university. Then he caught polio, poor guy, just a couple of years before the vaccine was invented, and had to abruptly enter an iron lung to stay alive. Sport’s loss was literature’s gain, because he’s a wonderful writer. This book tells the story of a WWI veteran who goes to visit a woman he met in Brighton during his leave. She says she is fiance; he can’t remember if she is or not. It gets weirder from there. The alleged fiance lives in an enormous decaying hotel in Ireland, and dies almost immediately after he gets there. For some reason he stays on, while the hotel crumbles around him. A bunch of stuff then happens that has something to do with Irish political history, I could not follow all that. But I enjoyed it nonetheless. Here is a taste, when they brought in the family dogs to try and chase out the huge family of cats who were living in abandoned rooms:

“But it had been a complete failure. The dogs had stood about uncomfortably in little groups, making little effort to chase the cats but defecating enormously on the carpets. At night they had howled like lost souls, keeping everyone awake. In the end the dogs had been returned to the yard, tails wagging with relief. It was not their sort of thing at all.”

THE SEIGE OF KRISHNAPUR by JG Farrell

I found this book in my house, but have no idea where or when I got it. It’s part of the EVERYMAN’S LIBRARY series – a fantastic series I used to read a lot of back when I haunted the Harare City Library – so I assume I picked it up based on that alone. And once again EVERYMAN’S LIBRARY has come up with the goods. I’d never heard of this JG Farrell, but this is a banging book. It is a fictionalization of the Siege of Lucknow in 1857, which I’d also never heard of, in which a group of English colonials withstood a long siege by the rebellious Indian army. It is a hair-raising story of delicately brought up people reduced to eating rodents, but it is a also a hilarious book of ideas. Try this description of a young man:

“From the age of sixteen when he had first become interested in books, much to the distress of his father, he had paid little heed to physical and sporting matters. He had been of a melancholy and listless cast of mind, the victim of the beauty and sadness of the universe. In the course of the last two or three years, however, he had noticed that his sombre and tubercular manner was no longer having quite the effect it had one had, particularly on young ladies. They no longer found his pallor so interesting, they tended to become impatient with his melancholy. The effect, or lack of it, that you have on the opposite sex is important because it tells you whether or not you are in touch with the spirit of the times, of which the opposite sex is invariably the custodian.”

This gives you a flavour. It would have been really easy to write a book of stereotypes, because these poor starving people are so obviously getting what they richly deserve, but somehow he avoids it. Strongly recommend! So strongly in fact that I immediately read his next book TROUBLES. Of which more shortly.

THE EMPEROR by Ryszard Kapuscinki

Here is a book in which a journalist seeks out and interviews members of the court of Haile Selassie, the last emperor of Ethiopia, immediately after he is deposed. This is not too easy, as they either dead or in hiding. He is mostly able to find the most junior servants. The guy whose job was to put the pillow under his majesty’s feet; the guy whose job was to clean up after his majesty’s dog; the guy whose job was to bow every hour on the hour, so the emperor could keep track of time passing. It’s an interesting picture of what power does to people. Some say that the interviews are a bit too on the nose, and that in fact the whole thing is a commentary on the dictatorship in Kapuscinki’s native Poland. I don’t know that it makes that much difference; one great truth in life is that one autocrat is much like another.

Particularly interesting was how Selassie lost power, in inches, to the military council named the Derg, which itself became a pretty robust dictatorship basically immediately. I have been to a museum about this in Addis, where they directly display some of what they dug up from mass graves of the period, including heart-breaking passport photos of hopeful students with enormous 70s hair who laid down their lives for a better Ethiopia. I’ve also been to Selassie’s palace, where you can see the his-n-hers bathroom set up he had (pink and blue) complete with bullet holes in the mirrors from when things got real at the end.

A sad and weird read.

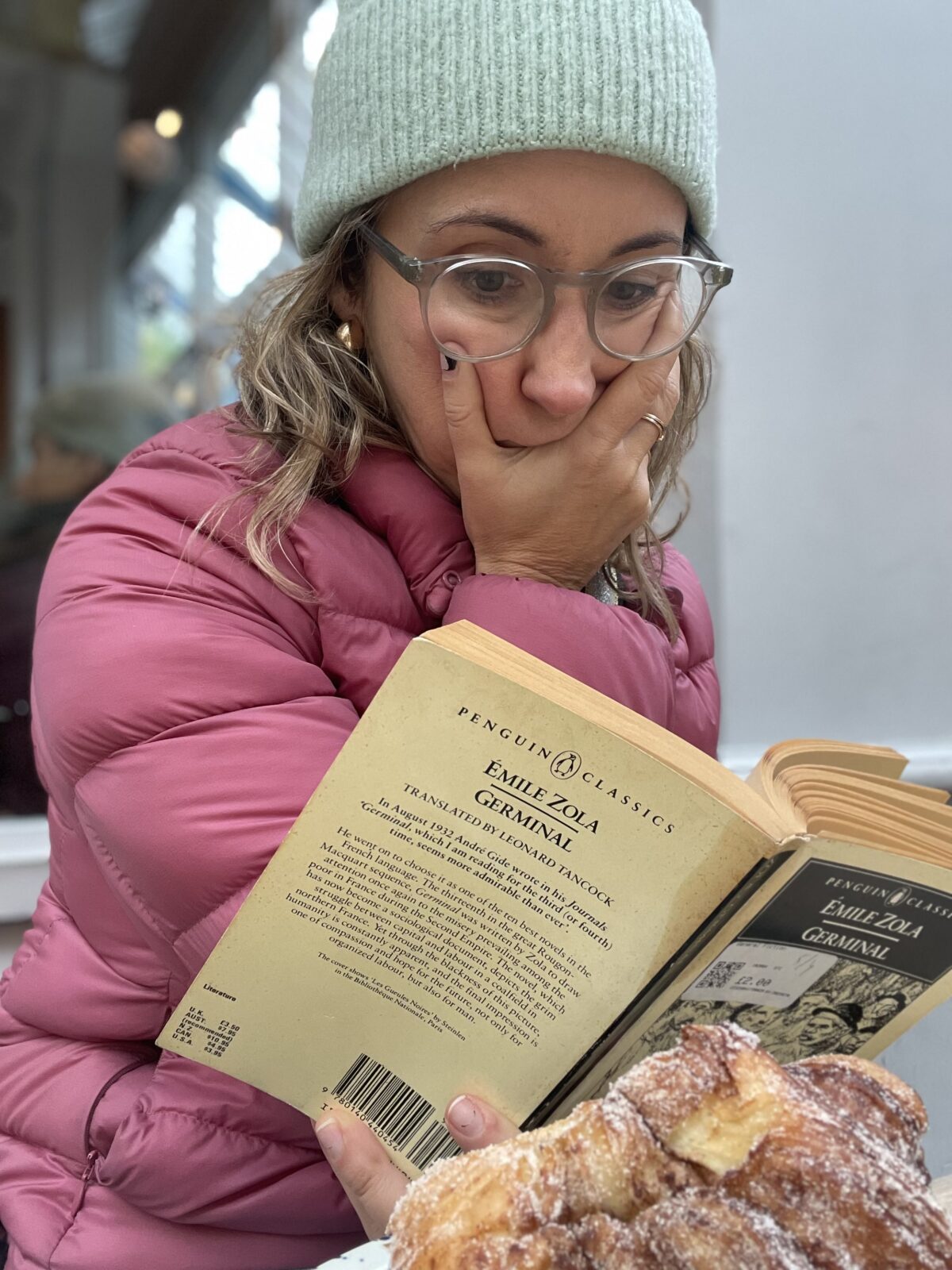

GERMINAL by Emile Zola

I thought I’d give this novel a bash to see how far my attention span has degraded. In my teens and twenties the vast majority of what I read was massive 19th century novels, and I was curious if I still had the appetite for all that tiny text, description of landscape, and casual misogyny. Good news: yes I do!

This one tells about a man walking through 19th century France looking for a job. He is facing starvation when he lucks into work in a coal mine. Cue a lot of interesting detail about 19th century mining practices. As you can imagine its not good: while they don’t get to have much to eat, they do get to have coal lung, and lets not even get into the ponies permanently trapped down there.

I was kind of hoping this story might be about how this guy was delighted to escape from starvation to near-starvation, and went on to build a happy family life in the mines. LOL no. He is inspired by the idea of communism and eventually convinces everyone else to strike. At this point, it started to feel very much like THE JUNGLE by Upton Sinclair (same story, except 1930s/America/ abbatoir), a book that wrecked me in a Chicago airport maybe twenty years ago. I could just see where we were going with idealism crushed, people starving, immortal logic of capitalism triumphant and etc, and I just couldn’t bring myself to go through it. So I guess the good news is my attention span’s fine, but the bad news is my emotional resilience is SHOT.

THE MAN OF PROPERTY by John Galsworthy

This is the first in a series of novels which is part of how Galsworthy won the Nobel. I enjoyed it, but I am not sure if I will read the whole 1000 page saga which I am told is ‘three novels and two interludes,’ wtf is an interlude. Anyway, this first novel tells about the unhappy marriage of Soames Forsyte and his wife Irene. Forsyte comes from a robustly bourgeois background, while Irene is poor. I have not googled it but I am 100% sure Galsworthy comes from a family with money, because he spends a lot of time banging on about how awful families with money are, how obsessed with property, etc

The couple have little in common and she SPOILER ALERT begins an emotional affair with her husband’s architect. She had already ‘locked her door’ to Soames, and eventually he becomes so enraged that he ‘asserted his rights and acted like a man’. I was really impressed that a book written this early takes marital rape so seriously. Irene is extremely distressed, and the architect is too, ending up killed in a carriage accident. Soames meanwhile is upset too, but mostly because he can’t understand why Irene won’t just accept that she, just like their big house, is his property.

A CONSPIRACY OF PAPER by David Liss

This book sounded great: a historical fiction set among the coffee houses of eighteenth century London in the lead up to the bursting of the South Sea Bubble. Ooh obscure early stock market drama! Count me in.

It is that, but it is also a detective story. I am okay with a detective story but it needs to move quick. And this one moved kind of slow. So I enjoyed all the fun research, maybe there was a bit too much research – there was certainly an awful lot of exposition – but anyway: I had to quit at about 150 pages.

I don’t always record books I don’t finish, but I can just imagine that in 10 years I will be looking for something to read, and think: oh, this looks good! So, here’s something for me in 2034: Sarah, you did not like this book.

NEVER LET ME GO by Kazuo Ishiguro

I loved this book the first time I read it, but on the re-read I was less impressed. It made me realize I guess that it actually functions very much like a thriller/detective story, and thus once you know what the mystery is, it is much less interesting. I also found it extremely depressing that SPOILER ALERT the clones don’t even consider fighting against their destiny – to have their organs slowly harvested. Why is that? What is the message? That we all are so deeply trapped in our worldview we can’t ever throw it off for any reason? I don’t know, maybe that’s true, but damn.