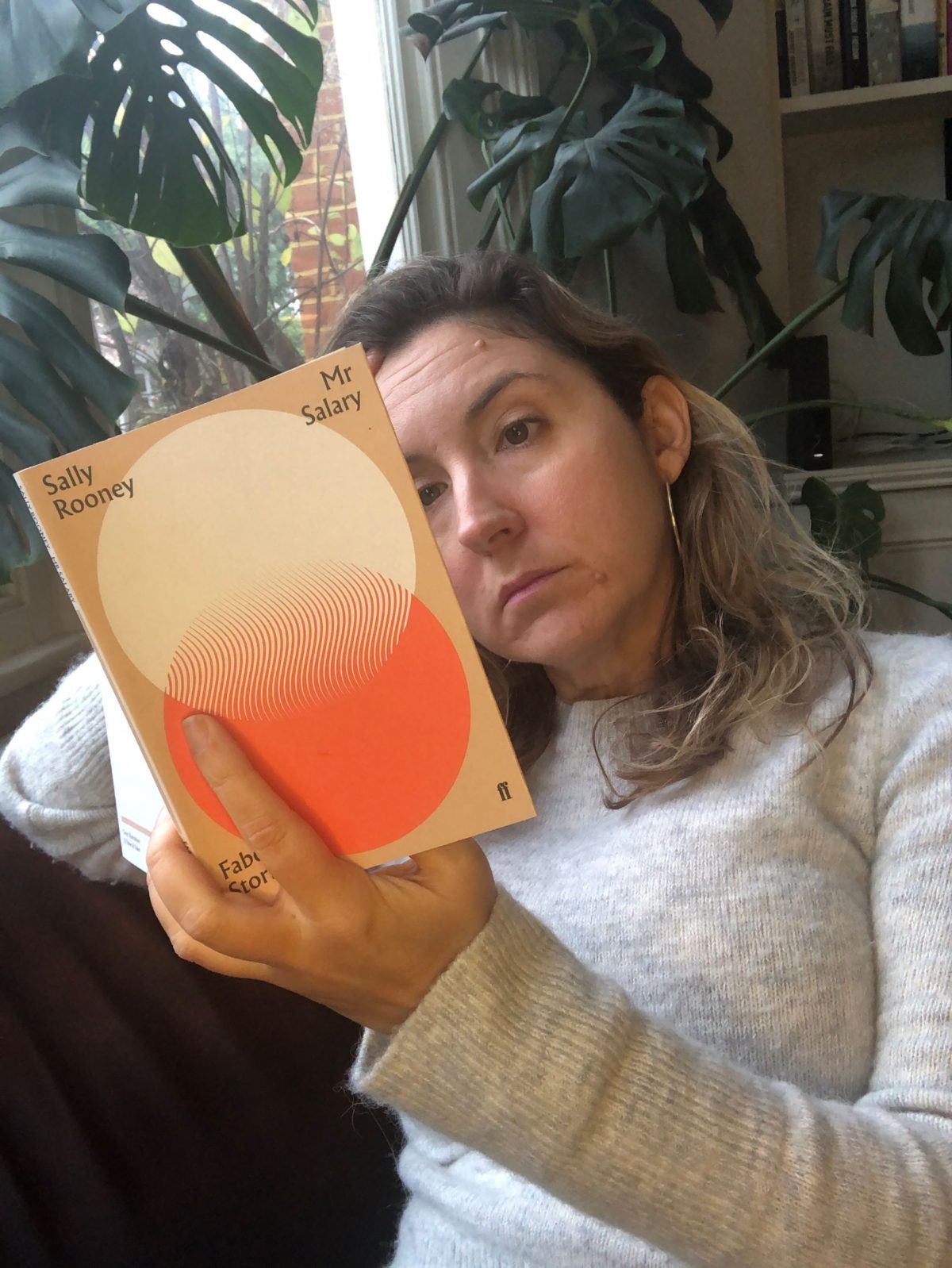

I enjoy a feminist dystopia as much as the next person, but in this case, maybe just stick with the TV show.

THE HANDMAID’S TALE is set in an alternative future where fundamentalist Christians have taken over the USA. Women have been returned to exceedingly traditional gender roles, i.e., gross old guys get whatever they want. They have wives, they have female servants, and they have concubines. Sounds pretty sweet. I mean for the gross old guys. Grisly for everyone else. Atwood said one of her rules in writing it was that no atrocity should be included that had not actually happened in history, and it is depressing to contemplate how much of this future dystopia is basically just a re-telling of the past.

It reminded me a bit of STEPFORD WIVES, in which ordinary men are given the option to have their wives’ brains rewired to produce a ‘perfect’ woman. What makes that book so compelling is how believable it is that given the chance, most men would take that option.

So, it was interesting; but I can’t say I enjoyed this book that much. It was all a bit lyrical and literary for me. There were some very questionable dreamlike sections. The TV show cut all those bookish bits. The book without the book. Much better!