I enjoyed this author’s first book, ACTS OF DESPERATION, and read an interview with her where she denigrated it, saying this one – ORDINARY HUMAN FAILINGS – was in her opinion much better. I am amazed. ACTS OF DESPERATION was grippingly grim, but had a enjoyably comic energy and a general direction towards sanity. ORDINARY HUMAN FAILINGS on the other hand is just grim. Like, so grim it starts to feel kind of ridiculous. It’s about child murder (beloved topic of UK cultural life), so obviously I did not expect it to be cheerful, but wow: every single person in it is a venal and depressing failure. I mean all of them. From the damaged mother, to her brother, the tragic alcoholic, to the money-grubbing journalist who writes about them – they are all victims or perpetrators. The only person who actually tries to do something positive is the gran, but don’t worry, there is a long explanation of how she only does this because she was not loved enough as a child. I mean, okay. I just had to quit it.

THE MINISTRY OF TIME by Kaliane Bradley

This is SUCH a fun book. It tells the story of a government program that manages to bring a handful of people from the past (specifically 16th, 17th, 18th centuries) into the present day. SPOILER ALERT, it is mostly a kind of rom-com about the relationship between a Victorian polar explorer and his present day minder, a government employee. All time travel books run the risk of getting into but-what-if-I-killed-my-grandfather territory, and I won’t say this book doesn’t get there. But who cares when it is so fun. Try this:

“He was introduced to the washing machine, the gas cooker, the radio, the vacuum clear.

‘Here are your maids,’ he said.

‘You’re not wrong.’

‘Where are the thousand-league boots?’

‘We don’t have those yet.’

‘Invisibility cloak? Sun-resistant wings of Icarus?’

‘Likewise.’

He smiled. ‘You have enslaved the power of lightning,’ he said, ‘and you’ve used it to avoid the tedium of hiring help.’

‘Well,’ I said, and I launched into a pre-planned speech about class mobility and domestic labour . . . and by the end I’d moved into the same tremulous liquid register I used to use for pleading with my parents for a curfew extension.

When I was finished, all he said was, ‘A dramatic fall in employment following the ‘First’ World War?’

‘Ah.’

‘Maybe you can explain that to me tomorrow.'”

That gives you a good sense. It’s a deeply thought though culture-clash story and I really enjoyed it. I don’t believe it would really be possible for a Victorian man to have a happy relationship with a contemporary woman, but there you go, that is just because I am a miserable feminist killjoy and takes nothing away from the story.

BANAL NIGHTMARE by Halle Butler

I liked this author’s last rage-filled book, THE NEW ME, and I like this one too. THE NEW ME was about an angry woman in Chicago who concludes she has wasted her twenties. BANAL NIGHMARE is about a pretty similar woman in her early thirties who has left Chicago to return to her hometown.

The main character is recovering from a break-up, and I guess the book functions as a prism for looking at the particular unhappiness that comes with deciding in early mid-life that you are going to have to start again. Every romantic relationship in the book is a mess, which makes it pretty depressing (and unlikely) reading. But I still enjoyed the miserable, defeated energy of the book.

LONG ISLAND COMPROMISE by Taffy Brodesser-Akner

God I loved this book. It is a family drama about the long term impact of a kidnapping, but who cares what it was about. It was the kind of book that as soon as I open it I know I am going to like it; it basically deletes you out of your life for hours at a time. Enjoy this, about an aggrieved woman about to give the eulogy at her mother’s funeral:

. . . Marjorie, who was normally a seismograph for people’s regard of her, had quickly become drunk on the wide-scale pronouncement of the category of grievances she frequently referred to (in crowds smaller than this, mostly gathered on folding chairs in a circle) as ‘her truth.’

The category of grievances that were her truth. LOL!

I loved the pull of the plot, but almost more I loved the weird freedom of the narrative voice. I’ll end with her describing some McMansions:

. . . And the details were atrocious: curling wrought-iron gates and shutters that couldn’t possibly work and stone-ish siding and my god, the columns: Corinthian, Doric, Ionic, tragic.

Now here is a separate paragraph just for the doors. The doors on these homes were huge. . .

THE FUTURE by Naomi Alderman

This is a fun novel in which the near future is densely imagined. I was not so much sold on the plot, which for me was a bit too close to wishful-thinking. If I was to summarize reductively, it pushed the idea that if we could just get control of Big Tech we could somehow solve the climate crisis.

I am not sure anything can solve the climate crisis at this point. I just hope we can hold on till human population peaks in 2100 and then it somehow heals itself as our species begins to decline back down to more rational numbers. In any case, I admired the density of the imagining, and loved some of the ideas. Try this:

“. . . . the sun will go supernova and boil the seas and we’re just one stinking species and species live and die, that’s what we do. There’ll be no audience and no final judgement and no redeemer is going to liveth and no one will come along at the end of the show and tell us our score and what we could have won.”

I like that idea, that I’ll never find out about the wonderful alternate life I could be living if only I’d made better choices.

THE ROAD TO NAB END by William Woodruff

It is rare, at least in English, to find a book written by someone who grew up really poor. And it’s very rare for that book to be pre-1950. Off the top of my head, I can think of LARKRISE TO CANDLEFORD and MY FIRST THIRTY YEARS and that’s about it. THE ROAD TO NAB END is one such. It’s a memoir of a childhood in the early 1900s in Blackburn. I had never heard of this Blackburn, but it was apparently a key starting point of the Industrial Revolution, especially in clothing manufacture. Unfortunately for the author, the Revolution was running out of steam as he arrived, and his family were at the sharp end of it. Try this:

“I think the damp worried me more than the cold. There was nothing to stop it rising through the flagstones that covered the floor . . . The washing hanging from the ceiling didn’t help either. The cold was sometimes so severe it made us forget the damp.”

“All meals were our favourite meals,” he says at one point, a sentence I have thought of often in my revoltingly privileged life of restaurants and ‘standards’ about food.

What makes it especially sad is that his parents moved to America in about 1910, and then, in a tragically poor piece of decision-making driven by homesickness, came back again, just in time for the father to be drafted into WWI and clothing manufacture to move to America. Here is his grandma, when challenged about moving to the US:

“And don’t give me that old buck about love of country. That kind of talk is for toffs. You keep the country, I’ll take the money. Frankly, I don’t care whether God saves our gracious king or not. I’m tired of the whole rotten lot.”

She certainly never came back, and ended her life rich and comfortable.

The presence of the WWI veterans is a particularly sad part of this book. One lies babbling in a bed in the front garden of the house across the street for twenty years, presumably from shell shock or a head injury.

It’s a clear, straightforward re-telling of a tough childhood, and it made me grateful for my cushy adulthood.

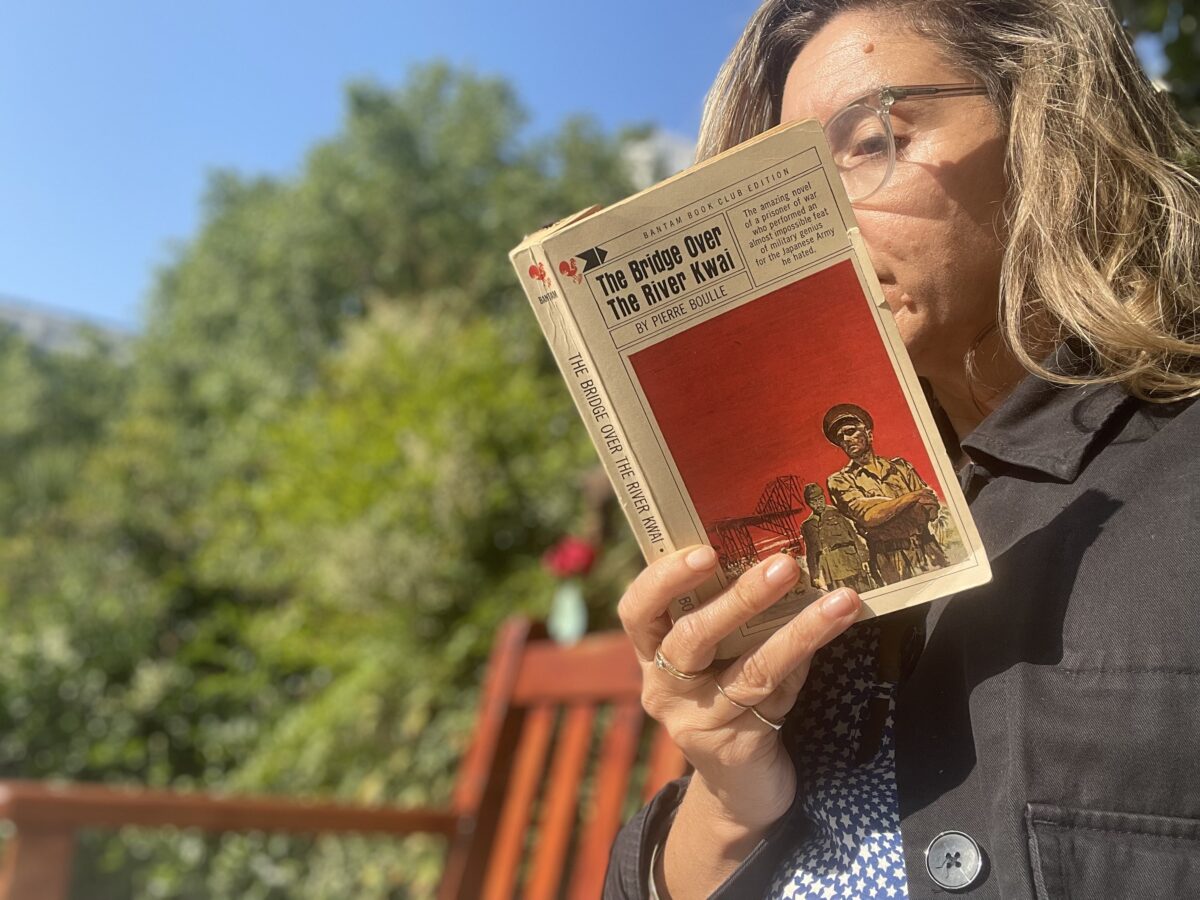

THE BRIDGE OVER THE RIVER KWAI by Pierre Boulle

I’m afraid I couldn’t finish this one, despite its truly wonderful cover and the fact that the edition I have is one of my favourite kinds, falling apart and with brown pages.

THE BRIDGE OVER THE RIVER KWAI tells about the Japanese use of Allied soldiers and forced labour to build a railway in WWII, a terrible project that killed about twenty thousand people. This fictionalized version had a tight plot in this interesting setting, but it was just too silly for me. It’s very much a mid-century male fantasy of tough geniuses.

Boulle was a veteran of forced labour himself, and I would have liked to read a book about his actual experiences. Apparently life being what it is, he did write one, called MY RIVER KWAI, but it has not endured enough to even merit a Wikipedia entry, while this kind of trashy version sold in the millions. Well done to him: I see he was so poor he was practically homeless after the war, so I’m glad he made some money. He then went on to write a wildly different book – wait for it – it’s PLANET OF THE APES (!?!) so he certainly sorted himself out

THE TRUE HISTORY OF THE KELLY GANG by Peter Carey

Here’s a book so good it’s almost depressing, like: how has this Carey guy done this?

It tells a fictionalized version of the life of the Australian bank robber Ned Kelly, in the imagined voice of Ned Kelly. There’s not a lot in the way of punctuation, and sometimes we run dangerously close to getting a bit cute, but overall it’s amazingly successful. Try this:

“Inside the shanty were much laughing and singing the shadows flitting across the curtains. Harry Power were dancing I heard not a word about the bunions he otherwise were whingeing about night and day. I never knew a man to make such a fuss about his feet.”

Or this, about a bushfire:

“God willing one day I would tell that baby the story of the apple gums exploding in the night the ½ mad kangaroos driven down before this wrath into the township of Sebastopol . . “

Or this:

“. . a number of Chinamen was engaged with a game of mahjong on a wide wooden plank. These was hard looking fellows all dried out and salted down for keeping.”

It takes you right inside his mind, very successfully. He grows up in poverty, the child of a transported man, and very much at the mercy of landowners and their corrupt police. He is almost forced into the life of the outlaw, and is greatly admired by the poor for his success. I always want to believe the life of an outlaw is glamorous, but this book shows what I guess I always suspect, which is that in fact it is stressful and difficult and given the choice we’d all rather be landowners. A fantastic book.

THE FLATSHARE by Beth O’Leary

A genre romance I read on the beach! I don’t remember too much about it, but big props to the author for the courage of not having the protagonists meet till fully half way through the book.

CONVERSATIONS WITH GOETHE by Johann Peter Eckermann

I knew this was an ambitious one, but as I have enjoyed such apparent stinkers as BOSWELL’S LONDON JOURNALS 1762-1763, I thought I would give it a go. I gave it a good two hundred pages but: yikes. The beginning is pretty interesting, when it is less about Goethe and more about Eckermann. Eckermann came from a really poor background – his family where subsistence farmers (and I mean for real; they only had one cow). He was clearly a bright and ambitious boy, and managed to get himself into school, where he has his socks blown off by what I can only call LITERATURE. You’d think coming from where he comes from, that he’d want to study e.g., law or e.g., medicine, something with money in it, but oh no. As he explains: “. . .I was dead set against undertaking a course of study simply for the purpose of getting a paid job.” However after a while he realizes he will have to at least appear to compromise, and agrees that he “would choose a course of study that led to a proper job, and devote myself to jurisprudence. My powerful patrons, and everyone else who cared about my worldly fortunes but had no idea how all-consuming my intellectual needs were, found this course eminently sensible.”

I just love that part, about his all-consuming intellectual needs. Poor guy. He drops out of university, and then makes a lot of generally bad financial choices of the kinds artists do make, but then luckily for him he meets Goethe. At this point, the book takes a turn for the dull. Goethe bangs on about a lot of stuff, mostly about how younger generations need to learn from him and his elderly compatriots and etc etc. Perhaps this dullness is not Goethe’s fault; maybe anyone whose conversation is recounted by someone who is a massive fan would seem boring. But in any case, I had to quit. One thing I did find oddly reassuring was how enormously famous Goethe did seem to be in his day, and how rather unfamous he is today. I guess it’s a comfort in its own way to know that no matter what you do, unless you get to Jesus or Hitler levels, history will not care.