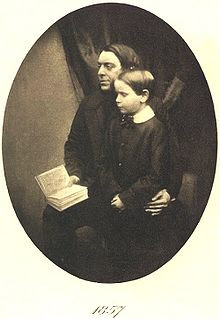

This book is about the relationship of a father and son, and is, as the author tells us early on “ . . . in all its parts, and so far as the punctilious attention of the writer has been able to keep it so, is scrupulously true”

Fabulous. I love a good effort to tell us in detail about your childhood, not least because I can’t ever imagine attempting such a thing myself. Who knows what the truth of all that is? Who can even remember it? I found this especially interesting because the author’s childhood happened in the 1850s, and I can’t recall ever reading an earlier version of memoir than this. I see Wikipedia calls it among the first psychological autobiographies, whatever that may be.

Edmund had a particularly interesting childhood, being brought up by fundamentalist Christians called the Plymouth Bretheren. Here he is making his first small rebellion, an attempt to find out what god would do in case of idolatry:

I knelt down on the carpet in front of the table and looking up I said my daily prayer in a loud voice, only substituting the address ‘Oh Chair!’ for the habitual one. Having carried this act of idolatry safely through, I waited to see what would happen. It was a fine day, and I gazed up at the slip of white sky above the houses opposite, and expected something to appear in it. God would certainly exhibit his anger in some terrible form, and would chastise my impious and wilful action

He is not struck down by lightning, and so begins a long path away from his father’s religion. His father has the entire Bible by heart, down to the minor prophets, and for ‘fun’ he likes to read Revelations and look for signs of the end of days. He is also however a complex character, being an eminent marine naturalist, who is really distressed by the first ideas of Darwin, and tries to reconcile what is obviously scientifically true with the seven days of the Bible by putting forward the idea that God did create the world in seven days, but that he created it so it looks millions of years old. The poor man is roundly mocked by scientists and ministers alike.

Eventually Edmund grows up and goes to London, as everybody it seems must do eventually. His father pursues him there with letters about scripture and molluscs, which are a great distress to him, and from which he quotes at length:

Over such letters as these I am not ashamed to say that I sometimes wept; the old paper I have just been copying shows traces of tears shed upon it more than 40 years ago

It’s a touching story of someone’s childhood, and I recommend it, though it left me a little sad. There’s something depressing about thinking of how everyone has their own story of their childhood, their own memories of their parents, all those stories, going way back into history, and mostly forgotten now.