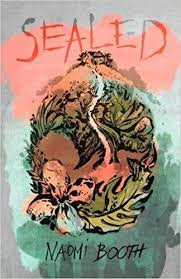

For a sci-fi novel to be successful, it always has to be about something other than sci-fi. And that ‘something other’ comes from the short list of human concerns we all know: love, loss, death, etc. This sci-fi novel is extraordinarily successful, and this comes in part from a quirky and original premise, but also because it is actually about something quite unusual too: birth.

Alice is heavily pregnant. Herself and her partner move to a rural part of Australia to get away from the increasing toxicity of the city, and from what Alice thinks is a outbreak of a dangerous disease, called Cutis, which means your skin starts to close over your orifices. Alice is hugely worried – she will only eat so called ‘protected’ foods; she washes herself after it rains; she thinks the government is covering up how bad Cutis is. Part of the success of the book is that it is unclear how much of this is her imagination and how much real. One reason she loves her partner Pete is that he is so much more relaxed than her, though of course, human relationships being what they are, this also annoys her.

The countryside has its own issues. The health services are shutting down. People are being evacuated in preparation for a ‘heat event,’ though they believe this is just a ruse to move them somewhere more central so services can be provided more cheaply. It all has an eerily plausible feel.

I won’t give away everything that happens, but let’s just say Cutis attacks the orifice most important for child birth, and a kitchen knife is involved. And yet, bloodshed aside, the novel is actually about hope, and about how you can have new beginning, even at the end of the world. It’s hard to explain. You’ll have to read it to find out. I recommend you do: it’s a very fine novel. Unless of course you are pregnant, in which case DEFINITELY DON’T.