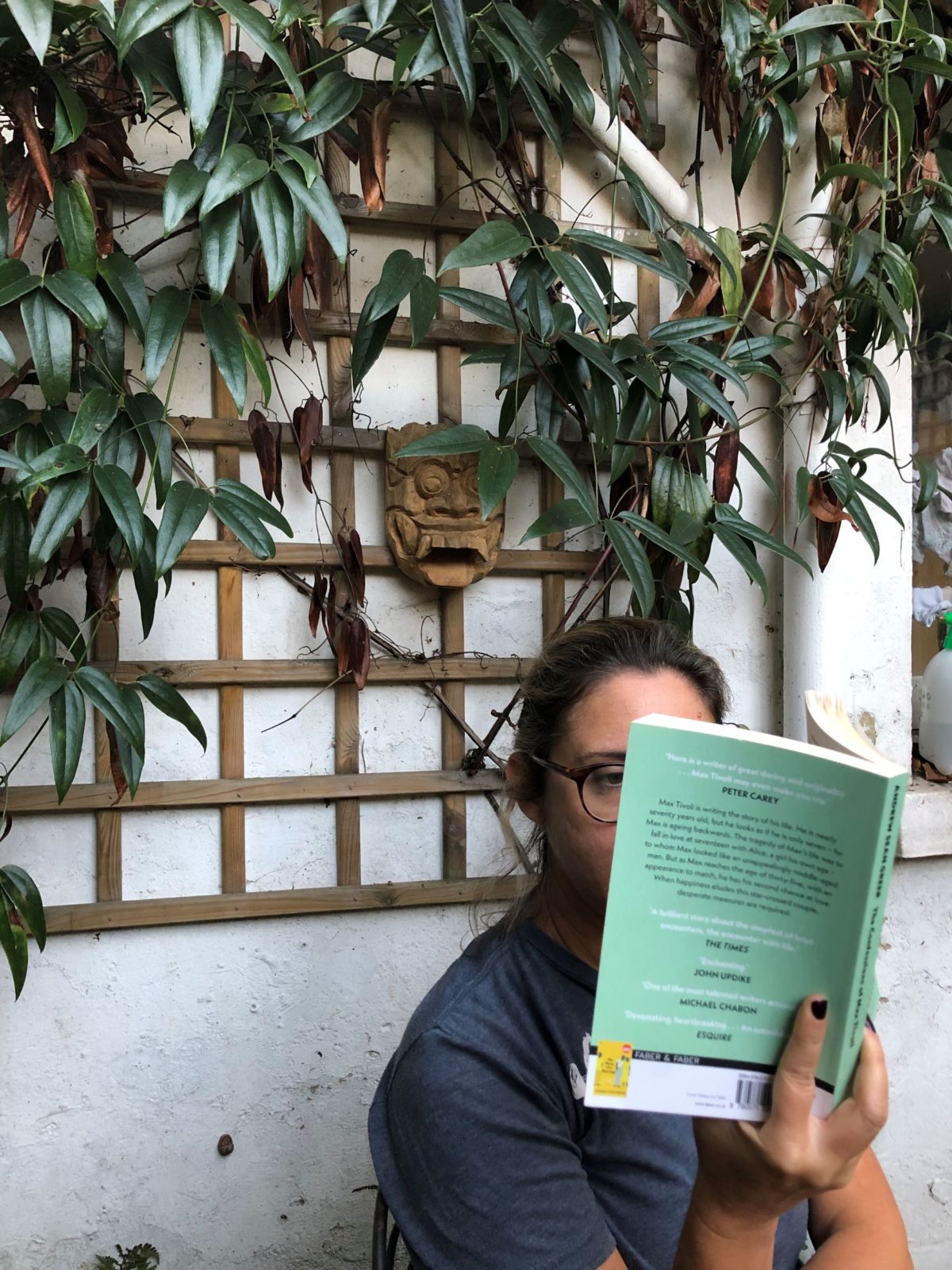

This guy is seriously having a lot of trouble working through his parents’ divorce.

I read his lightly (very lightly) fictionalized memoir, BIG ROCK CANDY MOUNTAIN, a few months ago. I enjoyed it so tried ANGLE OF REPOSE, for which he won the Pulitzer, a story of the very early days of mining in the American west. Despite the apparently wildly different subject matter they are in fact essentially the same story: a woman who wants a home marries a man who wants to keep moving. Rather charmingly, when asked if he had noticed the similarity he replied:

It never occurred to me that there was any relation between ANGLE OF REPOSE and BIG ROCK CANDY MOUNTAIN till after I had finished writing it.

It’s fascinating how little insight we all have into our own minds. How you write a 600 page novel and not notice that the main relationship is basically the relationship of your parents, about whom you already wrote a 600 page novel?

The best bit of this book were the letters, which the wife, a highly educated and artistic woman from the East Coast, wrote back to her friend (or more than friend), Augusta. Here apparently lies a controversy, because these are in fact extracts from the real letters of Mary Hallock Foote, whose life pretty closely followed that of the heroine.

The story cuts back and forth between the distant past and a present day author trying to write her story, apparently some version of Stegner himself. From this I learnt that Stegner is a pretty hardcore Republican who doesn’t mind bitching about young people. Also apparently not too much worried about plaigirism.

This lady was clearly a huge badass, having three kids in super dodgy desert locations while keeping up a career as an author illustrator. I found it especially interesting to learn about the economics of the early West. As the author puts it:

The West of my grandparents, I have to keep reminding others and myself, is the early West, the last home of the freeborn American. It is all owned in Boston and Philadelphia and New York and London. The freeborn America who works for one of those corporations is lucky if he does not have a family, for then he has an added option: he can afford to quit if he feels like it.

Interesting to think that we’ve all always been working for The Man.