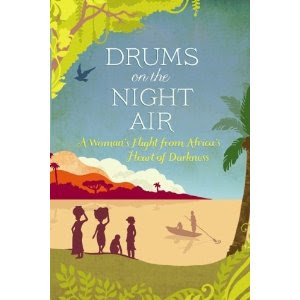

JUDGING A BOOK BY ITS COVER is an occasional series where I bring to your attention dreadful looking books I see in Nairobi’s better bookshops. How do you like this one’s title?

Drums on the Night Air: A Woman’s Flight from Africa’s Heart of Darkness

You have to assume it is either:

-some sort of strange Victorian travelogue

-an ironically comic version of same. (ie. please god,let it be a joke)

However friends, apparently not. Apparently this is an entirely un-ironic title for a book about ‘real’ experiences in contemporary Africa. Try not to puke now, before you read the back, so you save going to the bathroom twice. Here it is:

Veronica Cecil was twenty-five years old when her husband was offered a job at a large multi-national company in the Congo. Filled with enthusiasm for their new life, the couple and their eleven-month-old son set off for an African adventure. Very soon, however, Veronica began to realise that life in the Congo was not what she had imagined. Food shortages were an everyday occurrence; she felt like an outsider at the club in Léopoldville, which only the Belgians and other expats frequented; and flickers of violence were starting to erupt everywhere. Six months later Veronica and her family were sent to Elizabetha, a remote palm oil plantation on the banks of the Congo River. But even here paradise didn’t last. Civil war broke out, and the rebels captured the neighbouring town of Stanleyville and took all the whites hostage. Despite the fact that Veronica was on the verge of giving birth, the situation was so dangerous that she and her toddler had to be evacuated. Leaving her husband and all their possessions behind, she and her son began on a two-day journey through the jungle. But on the plane back to Leopoldville, the first labour pains began…

Oh didums! Food shortages! Shame! What, no nutella? And you weren’t as popular at the club as you thought you’d be? No wonder you had to flee!

Also, as a sidepoint, why did she think Congo would be paradise? I mean, I’m not saying DRC doesn’t have many good qualities, but paradise? Does this woman not have Wikipedia?

Now, please, if you have actually read this book, don’t be coming crying to me in the comments. I don’t want to get bogged down in actual content.