This book had a fun premise, in which a twenty-something slacker who is incidentally a werewolf gets sucked into a dodgy self-help movement. But then it went a bit sideways, and kind of trite, complete with fight scenes and ‘found family.’ I am not sure where I wanted this book to go, but it was not that way. But it was fun in any case.

Author: sarahwp

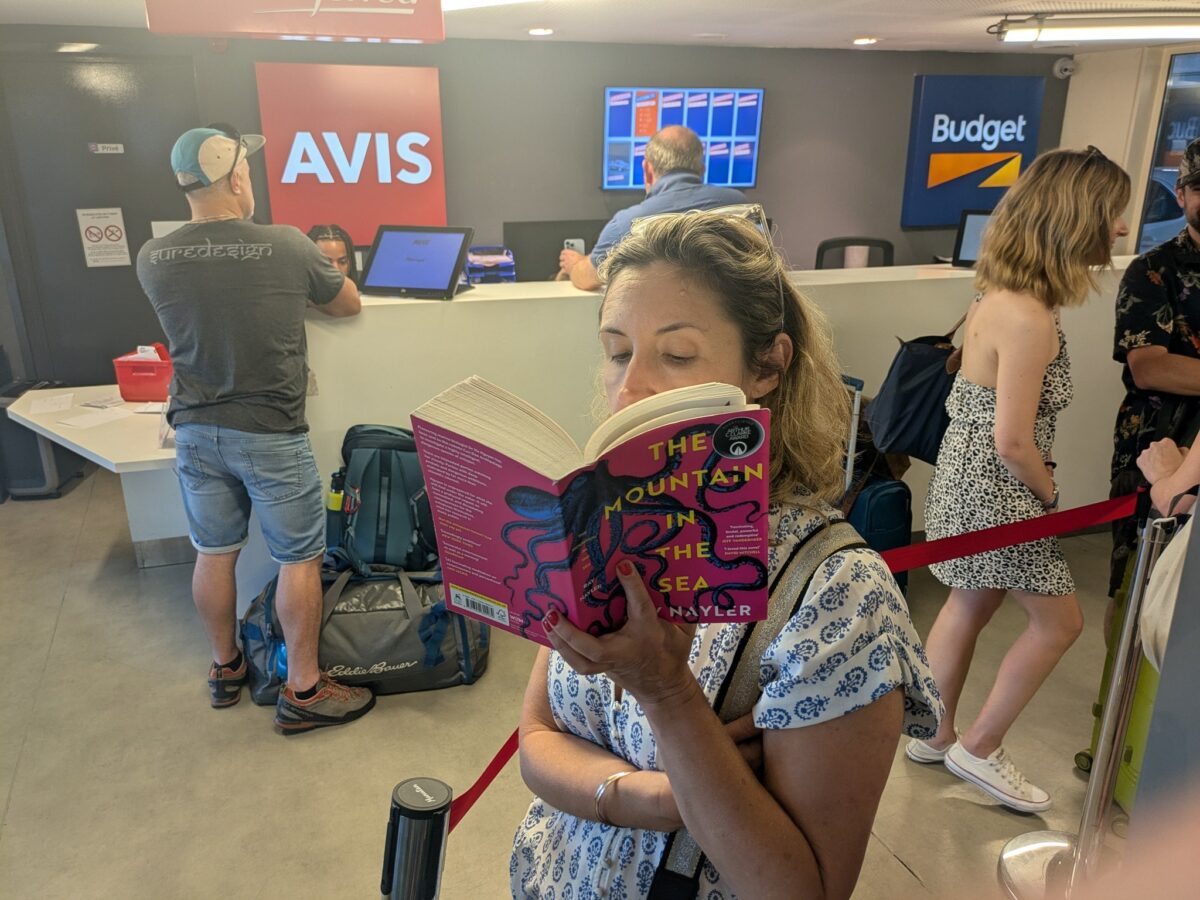

THE MOUNTAIN AND THE SEA by Ray Nayler

I gave up on this book, but I still enjoyed it. The 300 pages I did read were jam-packed with ideas. Basically it asks the horrifying question on what would happen if octopuses acquired our level of intelligence. This I consider a really big concern. Because let’s say dolphins did, or parrots, they don’t have opposable digits, so basically nbd. But octopi have four times our number of opposable digits! Its set in the far future, and is one of the few really believable far futures I’ve ever read. There’s a slave ship for scraping the last protein from the ocean, which has slaves on it because they are cheaper than robots, there’s a cyborg whose feelings are hurt because academics can’t agree if he is conscious or not, there’s customized hologram boyfriends, and that’s before the octopi get super intelligent.

There’s also a cool part about how our brain floats around in total dark, and our whole sense of the world comes from electrical impulses sent to it in its black chamber. I love this image.

LOVE AND SUMMER by William Trevor

I liked another book by this author, FELICIA’S JOURNEY. It was all about a poor Irish girl trapped by her society. It didn’t like this one nearly as much. It was also about a poor Irish girl trapped by her society. It started to make me feel like this guy just likes torturing poor Irish girls. This one was particularly grim. It’s about a girl brought up in a Catholic orphanage who goes out to be a maid and marries her employer and then SPOILER ALERT falls in love with a young man. From page 1 you just know that this isn’t going to be a story about finding happiness or escape. You just know everything’s going to turn out bad. And I just don’t have the tolerance for it. It’s almost like gratuitously miserable.

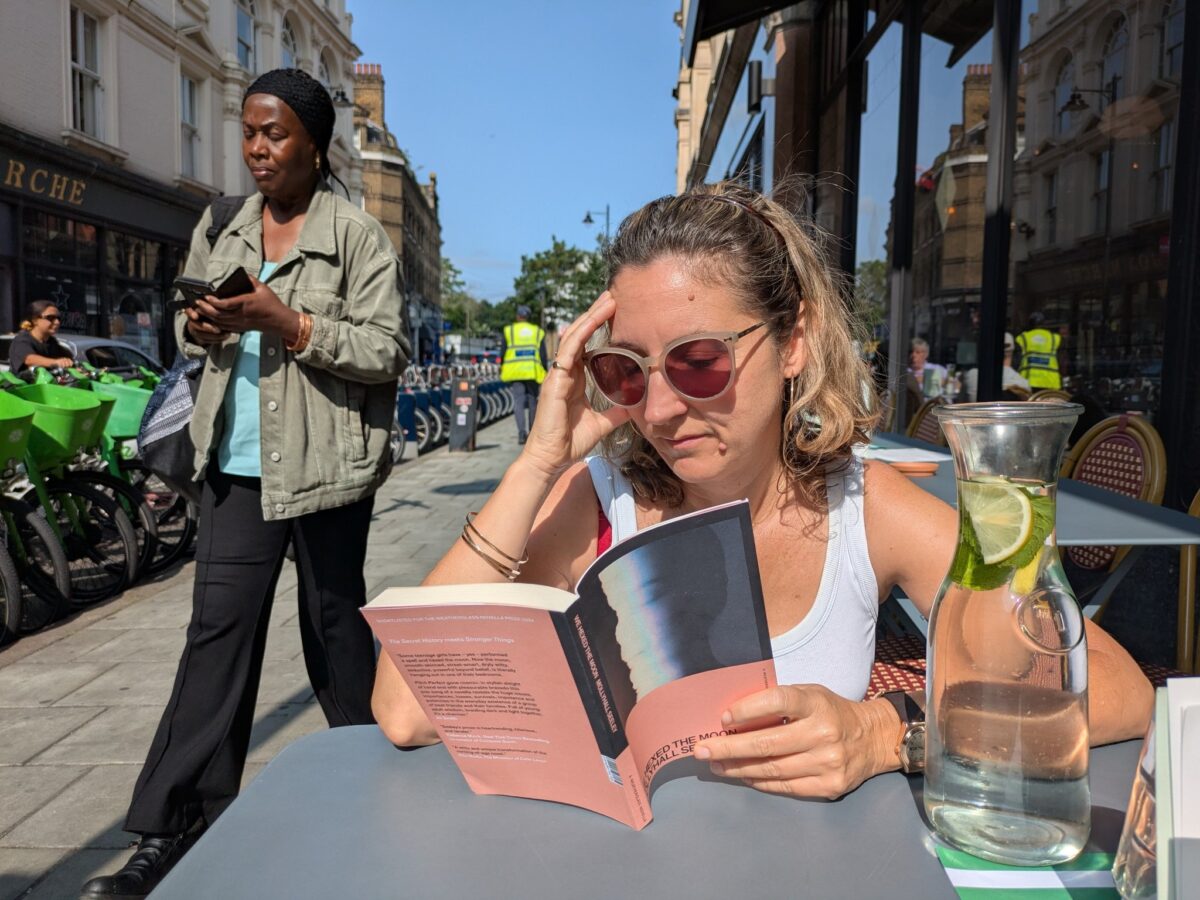

WE HEXED THE MOON by Mollyhall Seeley

Here is a book the author describes as being about: “four best friends who fuck around with The Moon and then very quickly Find Out about The Moon.” As you can maybe tell, it is a triumph of voice, and specifically GenZ voice.

The friends do a spell that pulls the moon from the sky.. The moon then comes to their house and wants answers. This plot, while wild, is really neither here not there. What matters is the vibe. Let me not talk about it, let me just quote extensively from the first page:

“Twitter is crumbling, fittingly, into a timeline of what is no longer called Tweets, now called Xs. Twitter is dead & so is nature, probably. Jen’s never having kids. That’s what Jen’s college application was about, framed through a lens of climate grief, ‘the sense of loss that arises from experiencing or learning about environmental destruction or climate change.’ Jen’s college counselor thought grief was a very powerful world. She said Why say grief and not sadness & Jen said Sadness is local, grief is cosmic. Global heating. Universal heating, maybe, who knows. So Jen’s not having kids but she is going to Yale.”

I’ve never read a book quite like it. I can’t say I know what it was ‘about’ – my female friendship? I didn’t care about the characters or anything like that, but I don’t think that was the point.

THE POWER OF NOW by Eckhart Tolle

This is the second time I have started this book, and the second time I have not finished it. Weirdly, both times I have got something out of it. It is a quite famous self-help book, and I think is the basis for some somewhat culty organizations. I don’t hold this against it, indeed I would query how good your self-help book is if no one can get a good cult out of it.

In the Introduction, Tolle tells us how he was suicidal one night, and thought he just couldn’t stand himself anymore. Then he wondered who was this ‘he’ who was experiencing himself. He had a sort of major insight, where he was able to see that his thoughts and feelings were not his inherent self. He then went to sleep, and woke up in such a state of bliss that he spent the next three months on park benches.

It sounds kind of crazy, but the point is very much the basic point of mindfulness – that we don’t have to identify ourselves with our thoughts. He goes on to build out this idea at some length, and I particularly liked some of his ideas – that you really, really, don’t need to think about your past. That it’s largely irrelevant. Also that you can decide not to create more pain for yourself. That you don’t have to accept anything as a ‘problem.’

He then gets a bit loopy, one-ness, Spirit, etc, and that’s where he keeps losing me, though one of these days I will get through it.

VIOLET CLAY by Gail Goodwin

I don’t know why this wonderful book is not more famous. I loved it. It tells about a woman trying to be an artist, and covers the terrible fear and dread of that activity better than anything I’ve ever read. Apparently there is a name for the coming-of-age novel of an artist, and it is kunstelrroman, and this is considered by some to be the first female one. (How do we feel about that this only happens in 1978?)

The book is written from the perspective of her early 30s, and covers her confidence as she graduates college (she won a college prize!), to the hard road of the next ten years, during which she has to do commercial illustration, and does less and less of her actual art. She has a LOT of casual sex (is this what the 70s was like? Does not seem hygenic), and suffers very much over how she is intentionally wasting her time and distracting herself from the fact that she is failing – not just in the world’s eyes, but in her own. She is interested in the dates of birth of famous artists, so she can calculate their age at the time of their first big success, and give herself hope that it is not too late for her.

Try this: “New York from across the river resumed the manageable proportions of a maquette, a harmless little table model on which I could project my dreams. It had looked like this when I rode the Carey bus into its center nin years ago from Newark. I still felt the old twinge when I looked at it now. I still wanted to leave my mark on it, even though it had left so many marks on me.”

Substitute London for New York, and I hear you Gail Goodwin, god I hear you. I see this author is still alive and was last published in 2020, so I am for sure going to read more.

THE SAILOR WHO FELL FROM GRACE WITH THE SEA by Yukio Mishima

Here is a book for boys, and especially the sort of boys who are interested in Japan. It starts off strong, with a 13 year old boy figuring out how to watch his mother undressing in her bedroom. She gets a sailor for boyfriend, so soon he is seeing more than this, and in particular the sailor’s ‘temple tower.’ (?!?)

The boy is in a creepy gang, and they SPOILER ALERT murder a kitten. I cannot tell you too much about this part because I skipped it. The boyfriend becomes a step-dad, and when he catches the boy peeping, does not beat him but has a healthy conversation with him about it. The boy is horrified, thinking this is unmanly, and so his creepy gang plans to SPOLIER ALERT murder the sailor.

Why?! What was the point of this?!? I am not sure. However, I enjoyed this description of a ship’s horn: “a cry of boundless, dark, demanding grief; pitch-black and glabrous as a whale’s back and burdened with all the passions of the tides, the memory of voyages beyond counting, the joys, the humiliations: the sea was screaming. “

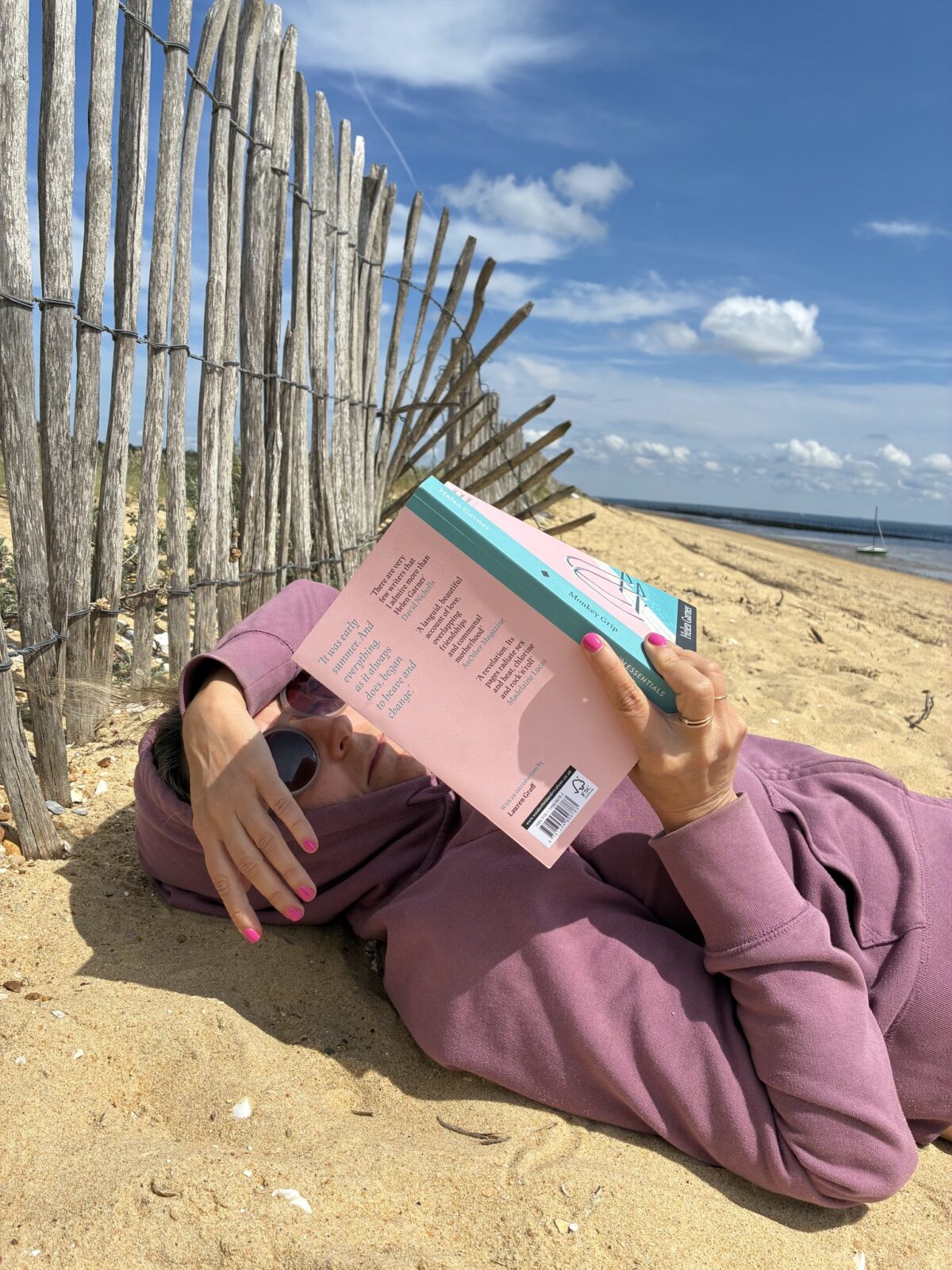

MOKEY GRIP by Helen Garner

Here is an book about the author’s experience being a young mother in 1970s Australia. She lived a kind of sincerely hippy lifestyle that I am not sure exists anymore. It’s all communal living, unsupervised children and relaxed attitudes to hard drugs. Also no one seems to have a job. It made me wonder wtf I am doing, really.

What I found particularly unusual and interesting in this book was the immediacy of the writing. She does not worry with backstory or context, you are just plunged right into the day to day. And its a very detailed day-to-day, she goes to the toilet a lot, something that almost never happens in books.

Like try this bit from near the beginning:

“Oh, I was happy then. At night our back yard smelt like the country.

It was early summer.

And everything, as it always does, began to heave and change. It wasn’t as if I didn’t already have somebody to love. There was Martin, teetering as many were that summer on the dizzy edge of smack . . . “

GREAT BIG BEAUTIFUL LIFE by Emily Henry

I don’t really read genre fiction, except for Emily Henry. She writes clever, fun rom-coms. I was excited for this new one to come out. But it wasn’t really for me. It is about two authors striving to be given the chance to write a celebrity’s memoir, and the main story is intercut with a summary of memoir’s plot. This means half the book is a summary of another, less good book? So I was underwhelmed, though the other half of the book was fun, standard, Emily Henry.

ADELAIDE by Genevieve Wheeler

In this book we see what happens when you date someone who’s not that into you.

Adelaide is madly in love with her boyfriend Rory. He thinks she is okay. She puts in an incredible amount of time and effort for him, and he enjoys it. To be fair, he does not lie to her. When she tells him she loves him, he explicitly tells her he doesn’t love her back. And yet somehow she just cannot let him go. I get it. It’s sad. She’s drinking too much, working too hard, and not eating enough, and SPOILER ALERT it all goes pretty badly wrong.

One thing I really enjoyed was that this book was set very precisely in recent years in London. The main character and I have been to the same plays, same exhibits, same restaurants. That was kind of eerie and I enjoyed it.