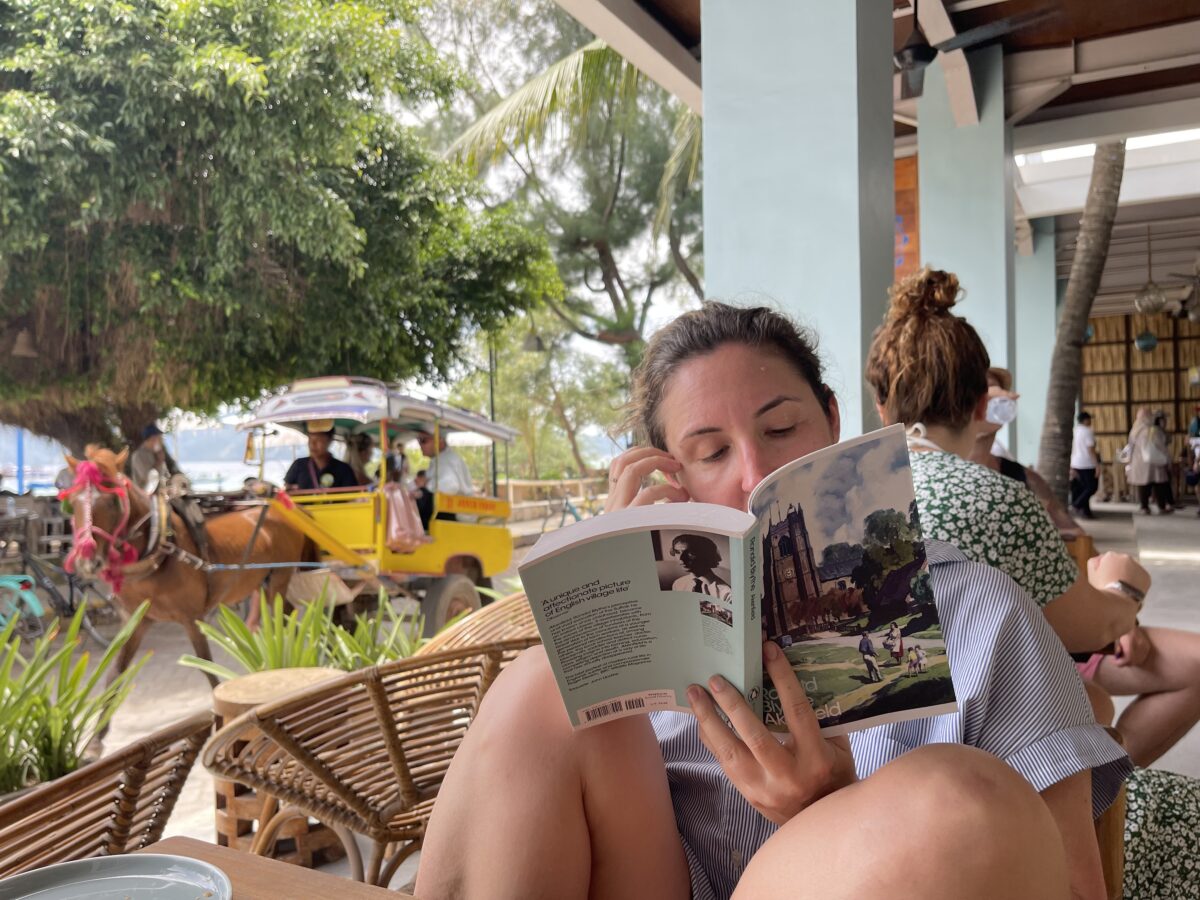

Here is a book that aches for the past, and a place. It’s about a childhood on a Zimbabwean farm, and let me tell you it is not recommended reading for the English winter. The author is about ten years older than me, and so bears the unfortunate burden of actually remembering the war. This makes her childhood days on the farm somewhat hair-raising. The farm they live on, Rainbow’s End, was previously owned by a family who were killed by guerillas in the war. One of the family was a little boy who SAT NEXT TO HER IN CLASS. When she moves in she finds HUMAN BLOOD ON HER WARDROBE DOOR.

And then apparently she goes on to have a blissful childhood, as the farm is also a game reserve, and she is mad for horses. She is also big on Zimbabwean food, which I enjoyed, it is not often I hear the joys of Mazowe described as they should be. In any case, it was interesting to read what it was like for young people to see the end of the war, and how it changed their perspective on what it had all been for. I am glad to be spared that burden.

I was struck by how much of Zim life is unchanged form the war. She talked about people ‘making a plan’ which I thought was a more modern framing, to do with our current issues, but apparently not. The book is full of the beauty of the landscape, and of dread. Here is an example sentence:

In late 1979, when our friends Bev and Fred Bradnick (in whose garden Lisa had once found a live grenade) were firebombed by terrorists on their farm on the Lowood Road . .

Can you believe that finding a live grenade is just a parenthesis? In other memoirs that would be a chapter. Bizarrely, what ages the author the most is not the blood on wardrobe doors, or the dead horses, but the discovery her father is having an affair. But there you go, I guess everyone has their own problems.