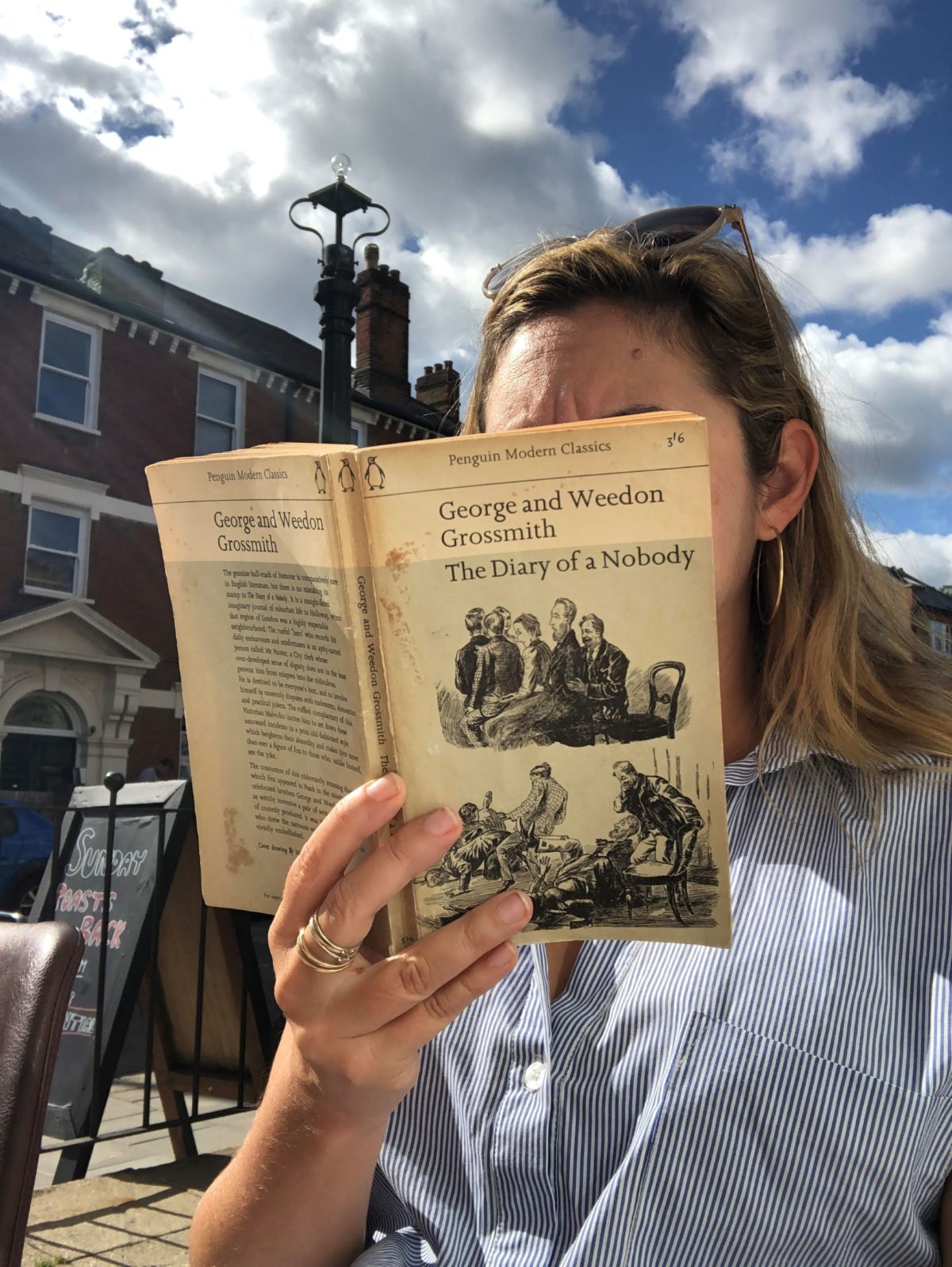

Here is a comic novel that has not been out of print since 1892. It’s hard to describe it’s appeal, beyond that it is fun to laugh at the bourgeoisie, especially I suspect if you are the bourgeoisie.

Charles Pooter has an office job and lives in the London suburbs. Don’t we all? He has worked twenty years in the same job, married to the same wife, and loves a little DIY. His diary is one of small victories and defeats: battles with the housekeeper; awkward dinners with ‘friends;’ his son’s interest in amateur dramatics. Here he is on housekeeping:

“I told Sarah not to bring up the blanc-mange again for breakfast. It seems to have been placed on our table at every meal since Wednesday… In spite of my instructions, that blanc-mange was brought up again for supper. To make matters worse, there had been an attempt to disguise it, by placing it in a glass dish with jam round it…I told Carrie, when we were alone, if that blanc-mange were placed on the table again I should walk out of the house

He also thinks he is hilarious, which is itself hilarious:

Gowing began sniffing and said: “I’ll tell you what, I distinctly smell dry rot.” I replied: “You’re talking a lot of dry rot yourself.” I could not help roaring at this, and Carrie said her sides quite ached with laughter. I never was so immensely tickled by anything I had ever said before. I actually woke up twice during the night, and laughed till the bed shook

It’s remarkably mundane, but he thinks it worthy of a diary, and like Peyps, thinks it will be read when he is dead. I found it very funny at the time, but as I write this blog I wonder if in fact I did not find it rather sad. I guess everyone has to try their hardest to assign meaning to their little lives, and who can say what level of meaning is ‘enough.’ Cult leaders have probably taken it a little too far. Everyone else, have at it, I say.