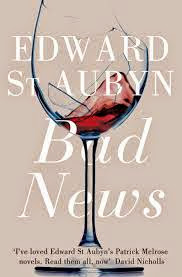

In this novel, the second in the Patrick Melrose series, Patrick is in his twenties and struggling with a major drug addiction.

As with the other novels, there is much precise prose to enjoy. As, for example, “he could feel the onset of withdrawal, like a litter of drowning kittens in the sack of his stomach.” Or, this, on stepping out into bright daylight: “This must be what the oyster feels when the lemon juice falls.” Or: “Kay told him about her own dying parents. ‘You have to start looking after them badly before you’ve got over the shock of how badly they looked after you,’ she said.

However, I’ve yet to read a novel about addiction that isn’t fundamentally dull, and this novel is no exception. St Aubyn does his best, structuring the novel around a few days during which Patrick is collecting his father’s ashes, but there’s not much he can do with the boring routine of wanting to shoot up, and then shooting up, and then feeling bad and wanting to shoot up again. I guess ex-addicts remember it as thrilling, but I struggle to find it so. There are some particularly bad pages where he recounts the various fragmented voices he heard while high, which are almost as bad as a dream sequence.

I know it’s mean of me, but it’s also hard to feel bad for someone who admits he never “spent less than five thousand dollars a week on heroin and cocaine,” and who gorges on expensive wine he doesn’t really taste. Presented with a large bill:

He was secretly pleased. Capital erosion was another way to waste his substance, to become as thin and hollow as he felt, to lighten the burden of undeserved good fortune, and commit a symbolic suicide while he still dithered about the real one. He also nursed the opposite fantasy that when he became penniless he would discover some incandescent purpose born of his need to make money.

There’s also a bit of misogyny. Here is his entirely unbelievable attempt to write from a woman’s perspective:

It was enough to make a girl feel guilty about being so attractive. She tried to avoid it, but she had spent too much of her life sitting opposite hangdog men she had nothing in common with, their eyes burning with reproach, and the conversation long congealed and mouldy, like something from way way way back in the icebox, something you must have been crazy to have bought in the first place.

I knows boys think that girls think like this, but I’ve never met one that does.

So, Book 2 not quite as good as Book 1. I have hopes for Book 3.