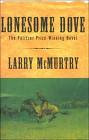

This one is 900 pages, but I promise you it goes down incredibly quick, like a cold glass of water after a long ride across the dusty plains.

As you may suspect from this rather tortured similie, it’s another western novel. Bizarrely, my third this month. I can’t recall when, if ever, I’ve read a novel of the American West, and now I’ve done three in three weeks. This has happened largely by chance, but by about page 700 I was completely ready to chuck it all in and be a cowboy. I am so up for drinking buttermilk, eating sourdough biscuits, and spitting tobacco, it’s not true. Also I want to go round calling people whores like that’s totally acceptable. All I need is a gender change, and for the American West still to exist.

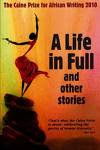

LONESOME DOVE, which won the 1986 Pulitzer Prize, tells the story of a cattle drive which starts in Texas and crosses over 3000 miles to arrive in Montana, establishing the first cattle ranch in that state. It’s a vast novel, and there are many ways you could see it. On one level, it’s a novel of the American landscape, taking us from the heat and dryness of the South to the snow and mountains of the West, and as the group struggle through rivers, across dry plains, and round tiny towns, it’s a monument to the sheer scale of the country. On another level, it’s a kind of elegy for what was lost when the settlers arrived. The leaders of the drive, Gus and Call, were once Texas Rangers, who existed to keep settlers safe from Indians. Now that they have ‘won’ they have time to consider what may have been lost. The book is full of encounters with various small Native American groups trying to find a way to survive. The Rangers, who knew the plains when they were full of buffalo – so full you could ride for a hundred miles along a single herd – are horrified by what seems to be the disappearance of that animal. They pass now roads of bones, the only remnants of these herds.

On another level, and this is the level on which its most engaging, it’s a story of the relationships of the group, from Newt, the yongest, newest hand, to Sean, the new Irish immigrant, to Jake Spoon, the gambler on the run from the law, to Lorena, the prostitute accompanying Jake, to Call, the old Ranger who feels his life’s work is over, and that it has largely been a waste. There’s friendship, and enmity, and personal growth, and death. Here’s my tip: DON’T TRUST MCMURTRY. You might think, oh, this character’s too important to die, that character’s too central to this plot arc to die, he can’t kill them, he won’t kill them. Oh yes he can. OH YES HE WILL.

It’s a very funny novel. Here’s a man who own a tawdry saloon in a tiny town:

Once as a boy he had carried slops in a restaurant in New Orleans that actually used tableclothes, a standard of excellence that haunts him still.

Here’s Call, on the subject of when to ride over into Mexico on raids:

Men he’d ridden with for years were dead and buried, or at least dead, because they’d crossed the river under a full moon.

I think dealing with that inconvenience, people who aren’t men, is very difficult when writing about the profoundly male world of the American West, and it is here that McMurty stumbles. There is a gang rape scene written from the victim’s perspective, that I found very dubious, and some odd observations – here’s one, on a prostitute named Maggie:

Maggie hadn’t had it in her to refuse a man. It was the only reason she was a whore, Call had decided – she just couldn’t turn away any kind of love.

What total nonsense. I had to stop at this point and do a quick Google to find out if this book was written in 1986 or 1886.

However, overall, a great novel. I strongly recommend it, and am currently trying to restrain myself from pouring a glass of buttermilk, whatever that is, and starting right in on the sequel.