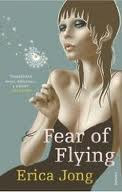

This book tells the story of Isadora Wing, who while at a conference with her second husband, the psychologist Bennett, falls madly in love with another psychologist, Adrian. She is confused about her feelings for Bennett, but certainly knows that she is bored and unfulfilled sexually, so she decides to run away with Adrian.

She and Adrian drive around Europe drunkenly and pointlessly, and the novel begins to move back in time. We learn about Isadora’s past relationships, with special emphasis on all the sex she was or wasn’t having. Eventually left on her own in Paris, Isadora has a sort of crisis of confidence regarding her inability to be by her self. She decides in the end to go to London to find Bennett, but the suggestion is very much that the most important peace that she has made is with herself, more than with any man.

Apparently this book was a massive bestseller when it first appeared in 1973 (it has since sold 12.5 million copies in 27 languages), and spoke in particular to women, who rejoiced in its sexual frankness and open discussion of female freedom.

Frankly, this response puzzles me a bit. I was kind of like: what? She doesn’t want to get married. She wants to have a career. She likes to have sex. I don’t really see the big deal.

But I guess that shows that we have come a long way since 1973, and that a lot of women before me had to fight a very long hard road, for me to be able to read this book, and find it simply puzzling.

It reminded me quite a lot of Doris Lessing’s THE GOLDEN NOTEBOOK, another book about a woman’s valiant struggle, that now seems to me unimpressive. It’s also similar to THE GOLDEN NOTEBOOK in it’s interest in psychiatry, in recounting dreams in detail (NB Authors: this is always boring), and in banging on in great detail about periods, as if no one’s ever written about them before. Which, maybe nobody had.

With all the sex stuff it also reminded me of the other old friend of this blog, Henry Miller’s TROPIC OF CANCER, but let’s not hold that against it.

Anyway, I admired the book. It’s impressively honest, the style is informal and fun, and the story compelling. It’s also rich with quotable quotes:

“Women are their own worst enemies. And guilt is the main weapon of self-torture . . . Show me a woman who doesn’t feel guilty and I’ll show you a man.”

“Because that was how I so often felt about men. Their minds were helplessly befuddled, but their bodies were so nice. Their ideas were intolerable, but their penises were silky.”

“ . . . in some fashionable sell-out profession like advertising . . .”

“All natural disasters are comforting because they reaffirm our impotence, in which, otherwise, we might stop believing. At times it is strangely sedative to know the extent of your own powerlessness.”

Martin Amis, on it’s release, called it “horrible and embarrassing.” That’s also very much in it’s favour.