Just a re-read of this, while I was recovering from a cold.

Tag: fiction

THE PROMISE by Damon Galgut

Here is a spectacularly well-written book that I admired, but did not enjoy. It tells the story of a South African family, across four funerals, where the supposed engine is a promise made to the domestic worker to give her the deeds to the house she lives in on their property.

Let’s start with what was great. Here’s a description of the family home:

Beyond it, a diorama of white South Africa, the tin-roofed suburban bungalow made of reddish face brick, surrounded by a moat of bleached garden. Jungle gym looking lonely on a big brown lawn. Concrete birdbath, a Wendy house and a swing made from half a truck tyre. Where you, perhaps, also grew up. Where all of it began.

BOOM. Amazing, and if that does not speak to my minority I do not know what does.

The cast of this book is large, and it’s amazing how the author seamlessly moves between perspectives. He also has a lot of fun poking holes in his own illusion. One lonely woman sits with a cat on her lap, and then he tells us maybe she doesn’t; maybe he will leave her truly all alone. This is both annoying and fun.

Given this mostly seems to be compliments, I struggle a bit to tell you what I didn’t like about this book. I think, first off, it annoyed me that everyone in the book was either mean or sad. That’s just not true of real life, and it seemed kind of self-indugently despairing. Like everything is hard enough, I don’t need to deal with this ludicrously bleak world also. Omicron is quite enough right now. Also, it’s probably not fair, but this conflict about the domestic worker’s land never really got off the ground for me. It just seemed a sort of cliche attempt to make some kind of commentary (that other people have made far better) about South African inequality. Maybe he felt he couldn’t write a white domestic drama without foregrounding this issue? Maybe he is one of these old white people who mostly relates to race-based issues through the only back people they know, i.e., domestic workers? Okay, now that’s getting really unfair. I’m getting as mean as the people in this book. I blame it on Omicron.

WISE BLOOD by Flannery O’Connor

Here is a book that involves a man in a gorilla suit using an umbrella skeletron as a weapon, a hit-and-run accident that is not an accident, and some self-blinding with lye. Unsurprisingly, it is in fact a book about religion.

It’s a strange, Gothic Southern story, that I did not enjoy but some how admired for its insanity.

I guess what I took from this book is that human beings have a very high level of baseline crazy. Sometimes this comes out in belief in god, sometimes it comes out in belief in ghosts, sometimes in QAnon.

ONE FAT ENGLISHMAN by Kingsley Amis

I found Amis’ LUCKY JIM to be both hilarious and liberating. This story, like LUCKY JIM, is about an angry and selfish university professor, but this is where the similarity ends. LUCKY JIM was a cheerful and basically optimistic book about blowing up your miserable life. This is a bleak book about doing the same.

I did not enjoy it, but I admired it. Amis sticks doggedly to having a thoroughly unattractive protagonist. Self-involved, over-weight, anti-semetic, and those are just the headlines. He particularly dislikes women, despite spending most of the book trying to sleep with them. Here’s a sample:

A man’s sexual aim, he had often said to himself, is to convert a creature who is cool, dry, calm, articulate, independent, purposeful into a creature that is the opposite of these; to demonstrate to an animal which is pretending not to be an animal that it is an animal.

I struggled a bit with how it is that this unpleasant man managed to sleep with so many women over the course of the book. Perhaps standards were lower back in the day. Apparently Amis himself was a major philanderer, which occasioned the end of his first marriage. Interesting trivia, his second was to Elizabeth Jane Howard (whose Cazalet Chronicles I am so fond of, what was she thinkng ?!?), and when that ended he wound up living out his old age with his first wife and her third husband. These people GOT AROUND.

SWEET SORROW by David Nicholls

Here is an enjoyable book that made me wonder what is the difference between commercial and literary fiction. These are some first world problems, but what can I say. I did really spend quite some time trying to think how it was that this engaging, servicable story about first love so was utterly competent and so completely forgettable. I think it is on some level because the author is not actually fighting any battle with himself in writing it. There is no vulnerability. It is almost clinically well paced and emotionally balanced.

Perhaps though vulnerability is overrated. It was very funny. Try this, from the teenage boy who is our narrator:

As with people who had good teeth and confident smiles, I was instinctively suspicious of people who got on with their parents, imagining that they must have some secret binding them together. Cannibalism perhaps.

Or this, from him again when a new theatre troupe is introduced at a school assembly:

As we feared, it was another attempt to convince us that Shakespeare was the first rapper.

That ‘as we feared’ really made me laugh. These was one interesting insight in it though. It’s about how madly he fell in love with this girl:

I had never in my life, before or since, been more primed to fall in love. . . If I’d been busier that summer, or happier at home, then I might not have thought about her so much, but I was neither busy nor happy, so I fell.

I bet if we look into when we have most painfully fallen in love we might find that what drove it was less that the person was actually perfect and more that the circumstances of our lives made us need them to be perfect.

THE DUD AVOCADO by Elaine Dundy

Here is a book about how we should all be grateful to the women who came before. It tells the story of a young American woman on what is basically a gap year in Paris in the 1930s (funded of course by family money, try not to feel too enraged). It is just incredible what goes on. People make her dance with them when she has told them no, they expect her to ‘know how to cook,’ some guy announces that:

All tourists are she

And she still falls in love with him. Wtf. Later we find out he was trying to traffic her into sex work but she still has fond feelings for him (?). I mean how did these girls get anything done? The issues are plenty.

The book is fun and insightful. Try this:

It’s amazing how right you can be about people you don’t know; it’s only the people you do know who confuse you

Or this, which I think is true about many people who begin, but do not finish, a career in the theatre:

The thing about him, though, was that he thought he was in the theater for Art, whereas he was really in it for laughs.

Apparently Dundy’s husband, theatre critic Kenneth Tynan, encouraged her to try writing a novel, as he thought her letters good, but was then horrified when THE DUD AVOCADO was a bestseller and instructed her to never write again. Meanwhile he was cheating on her left and right and spanking her though she was not into it. She began her second novel immediately.

I mean I didn’t enjoy this book that much but I am just amazed and impressed this lady held it together for long enough to get it written. Truly earlier generations were fighting some battles.

THE MAN IN THE HIGH CASTLE by Philip K Dick

This book presents an alternate reality in which the Germans and Japanese won the second world war. It has some interesting parts: for example, it imagines the internal struggles after Hitler dies (who would it have been: Goebbels? Speer? The mind boggles); it imagines what the Nazis would have done to African people; it imagines what it would have been like if Japanese culture became American culture; and so on. Sounds like a good book, right? But actually it turned out kind of boring. It covers a bunch of characters who are doing a bunch of things, but you don’t really believe in any of them and they all seem kind of the same person.

While the book was dull, the Wikipedia entry on it was certainly not. Philip K Dick led a wild life. First off, there is the five wives. That is always a red flag. The third one (who he later involuntarily confined to a psychiatric institution, but never mind that), was the one who inspired this book, largely because he needed her to think he was working, so he needed her to hear him typing, so he started typing, and ended up with THE MAN IN THE HIGH CASTLE. He never made much money, and took a lot of speed, and then when he tried to get off speed didn’t go to NA or whatever like a normal person but entered a sort of cult (Syanon), and all this was before he started to have religious visions (triggered by light glinting off a stranger’s necklace). When he died he was buried under the tombstone pre-prepared for him 53 years before by his parents, who determined he should be buried next to his twin who died in infancy. None of the wives ojected. I mean: it all went on.

CROSSROADS by Jonathan Franzen

Okay: I am about ready to give it up for Jonathan Franzen, and concede he may indeed be America’s greatest living novelist. Because this thing is LIT.

It tells the story of a nuclear family, over a period of about a year, from each of their perspectives (mom, dad, son, daughter, other son). From pg1, I was in. We open in

. . . the nursing home in Hinsdale, where the mingling smells of holiday pine wreaths and geriatric feces reminded him of the Arizona high country latrines. .

MWAHAHAHA. The father is a deputy minister at a Protestant church. He feels a sad kinship with the “dusty creche steer,” and is conducting an awkward flirtation with a parishioner. He is generally terrible at it, though he does get her to accept some vinyl records from him.

“He was not so bad at being bad as to not know what sharing music signified.”

Later he finally manages to get it together with his parishioner.

With a sigh, she closed her eyes and put her hand between his legs. Her shoulders relaxed as if feeling his penis made her sleep. “Here we are.”

It might have been the most extraordinary moment of his life.

The book is so incredibly well observed (‘that type of disinfectant unique to dentist’s office’ I mean god does he carry a notebook EVERYWHERE), so impressive in its creation of different points of view, so successful in concluding everyone’s arcs, I am just like DAMN

According to my blog, when I read a previous novel of his, FREEDOM, I was so overcome that I stopped on p38 to write a blog post about how much I already loved it. This was back in 2011, and it’s probably a good thing it was a while ago, because that book, like this, is a novel of a single nuclear family. I’d probably be able to see more of the authors tricks and obssessions and so be less impressed. As it is, let me just say again, DAMN.

BEAUTIFUL WORLD, WHERE ARE YOU by Sally Rooney

Regular readers know I love Rooney’s CONVERSATIONS WITH FRIENDS, which is gnaw-you-own-arm-off wonderful. I didn’t love BEAUTIFUL WORLD as much, but then there is not much I do love as much.

BEAUTIFUL WORLD is a book about romantic relationships, and seems to have a lot of anxiety about the fact that it is about romantic relationships. It seems like there is a concern that this is a non-serious topic to write about. I mean I have that concern myself, but this is just because I am trapped in patriarchy like everyone else, and what women choose to write about has long been dismissed as unserious, unlike, for example, the rape-and-murder that men like to write about in airport thrillers.

The story focuses on a pair of female friends, who are living some distance apart. It chronicles each of their relationships with their boyfriends, as well as their own friendship, which is largely conducted by email. The emails are every alternate chapter, and are full of self-pity and trite criticism of ‘capitalism.’ For example, one character says she was in the local shop when suddenly she:

thought of all the rest of the human population – most of whom live in what you and I would consider abject poverty – . . . And this, this, is what all their work sustains!

Leaving aside the high drama, it’s just not true that most of humanity works to sustain the Western way of life. I can think of a good billion Chinese people who have a few other things going on. Or try this:

. . . we’re living in a time of historical crisis, and this idea seems to be generally accepted by most of the population.

Anytime someone tells me we are living in a particularly seminal moment of history I always mark them down on the moron list. This is the over-privileged view of someone who has not lived through a war/recession/genocide.

I won’t even get into how mystified I am why these thirty-somethings are writing emails to each other. Is this supposed to be historical fiction? Does anyone other than one’s parents write emails?

Actually I enjoyed this book more than this makes it sound. It still sharp and heartfelt, and powerfully reminded me of the power and importance of human connection. I am not sure why I have bashed on so much

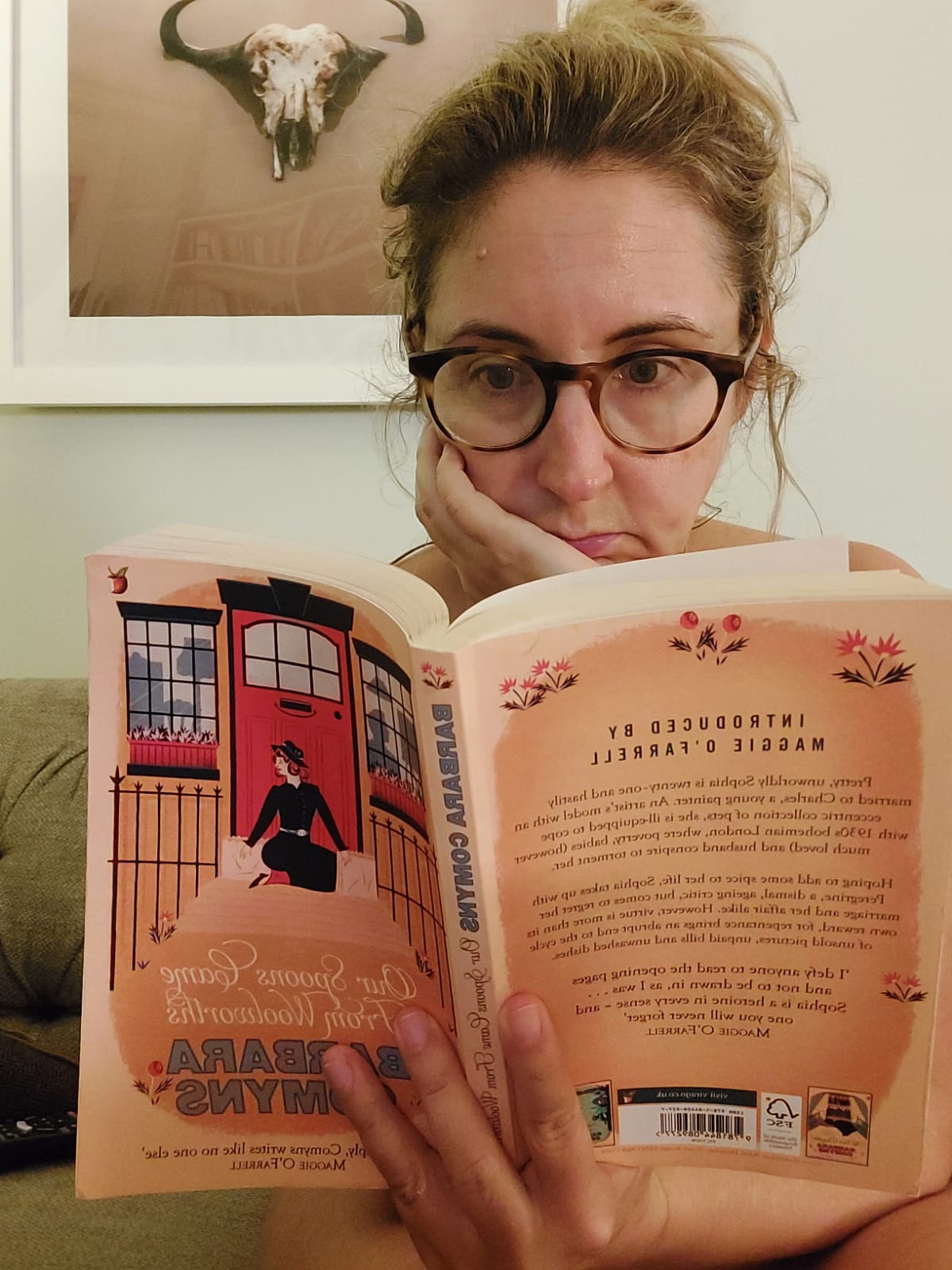

OUR SPOONS CAME FROM WOOLWORTHS by Barbara Comyns

This is a strangely inspirational book about failed painting careers, poverty and abortion. It tells the story of a young female art student who marries another art student. She gets pregnant and they are both horrified. Bizarrely, because it is the 1930s, or because he does not understand biology, the husband blames her. He refuses to take any responsibility for the baby, insisting he must focus on his art. The wife understands, because she too wants to be an artist. But instead she gets to do menial jobs for money. Eventually they split up and she ends up on the street with her baby. She manages to pull herself out of the situation by leaving London and getting a job as a cook.

Reading this summary you might think this is a depressing book. What is strange is that it is written in a light, comic tone, and can only be described as uplifting. For example, right near the beginning, speaking of her husband’s aunt, we suddenly get onto:

She even like my newts, and sometimes when we went to dinner there I took Great Warty in my pocket; he didn’t mind being carried about, and while I had dinner I gave him a swim in the water jug.

Her what? Her newts? Or try this:

The book does not seem to be growing very large although I have got to Chapter Nine. I think this is partly because there isn’t any conversation. I could fill pages like this:

“I am sure it is true,” said Phyllida.

“I cannot agree with you,” answered Norman.

“Oh, but I know I am right,” she replied.

. . That is the kind of stuff that appears in real people’s books. I know this will never be a real book that business men in trains will read. . . . I wish I knew more about words. Also I wish so much I had learnt my lessons at school. I never did, and have found this such a disadvantage ever since. All the same, I am going on writing this book even if business men scorn it.

I looked up the author afterwards and found the book was indeed quite autobiographical. What filled me with huge joy was to find that her husband does not even have a Wikipedia page. HAHAHAHAHAHAHAH. All that selfishness (sacrifice?) and apparently for nothing.

I am also really inspired by Comyns biography. It said she “worked in an advertising agency, a typewriter bureau, dealt in old cars and antique furniture, bred poodles, converted and let flats, and exhibited pictures.” It makes other author bios, involving lists of novels/essays/teaching posts seem maybe more ‘successful’ but somehow rather narrow and sad.