Christopher Isherwood is an English novelist who lived in Berlin as Hitler was coming to power, and these two novels capture that uncertain time. They tell the story of the various friends of one Christopher Isherwood, though he assures us that just because he has given his own name to the first person narrator “readers are certainly not entitled to assume that its pages are purely autobiographical” . Whatevs, Christopher Isherwood.

Christopher Isherwood is an English novelist who lived in Berlin as Hitler was coming to power, and these two novels capture that uncertain time. They tell the story of the various friends of one Christopher Isherwood, though he assures us that just because he has given his own name to the first person narrator “readers are certainly not entitled to assume that its pages are purely autobiographical” . Whatevs, Christopher Isherwood.

The “Christopher Isherwood” of the novels is struggling with his writing, and you can tell this in Christopher Isherwood’s novels. MR NORRIS CHANGES TRAINS is a rather dull story about a friend of the author’s who turns out to be a minor con man, while GOODBYE TO BERLIN is a lovely, acutely observed portrait of a lost world. It’s sort of frightening one person could have written them in a short period of time, showing how unreliable is inspiration, how unsteady talent.

Here is the description of a rich man: “ He was vague, wistful, a bit lost; dimly anxious to have a good time and uncertain how to set about getting it. He seemed never to be quite sure whether he was really enjoying himself, whether what we were doing was really fun. He had constantly to be reassured”

Or, on one of his friends whose boyfriend was leaving: “The afternoon he came to say goodbye there was a positively surgical atmosphere in the flat, as though Sally were undergoing a dangerous operation” This Sally is Sally Bowles by the way, as GOODBYE TO BERLIN is the basis of the musical CABARET.

Or, on a deer: “the roe went bucketing over the earth with wild rigid jerks, like a grand piano bewitched”

Or on an old woman “She sat on the edge of her bed with the photographs of her children and grandchildren on the table beside her, like prizes she had won”

Okay, I’ll stop there, but suffice to say I liked this novel.

Curiously, pre-war Berlin reminded me constantly of today’s Harare. I suppose this is not so surprising, as both places had faced catacylismic inflation, though as yet this has not resulted in the wholesale execution of minorities, at least in the latter. Just as street signs disappeared in Harare, to be used as coffin handles, the leather arm rests disappeared from German trains, as they were sold for leather, and people were to be found dressed in train upholstery. Christopher’s landlady recalls the days she would have “slapped the face” of anyone who suggested she scrub her own floors, which she now does happily, which reminds me of many a Zimbabwean reduced further than they ever thought possible. How awful is this: “The whole district is like that: street leading into street of houses like shabby monumental safes crammed with the tarnished valuables and second-hand furniture of a bankrupt middle class”

And I don’t know if its just because I have taken 8 plane rides in the last fourteen days, but this part also struck a sad chord for me: “Where in another ten years, shall I be, myself? Certainly not here. How many seas and frontiers shall I have to cross to reach that distant day; how far shall I have to travel on foot, on horseback, by car, push-bike, aeroplane, steamer, train, lift, moving staircase and tram? How much money shall I need for that enormous journey? How much food must I gradually, wearily, consume on my way? How many shoes shall I wear out? How many thousands of cigarettes shall I smoke? . . .What an awful tasteless prospect!”

It was in the very dark and distant old days, before this blog was begun, when the earth was still hot, and etc, that I began on Trollope’s series. I think I started out of order with the Barchester novels, and then moved on to the Pallisers; and THE PRIME MINISTER’S CHILDREN is the last. Now all that lies before me is his stand-alone single books, re-reading of the series in retirement, and of course sad and lonely death.

It was in the very dark and distant old days, before this blog was begun, when the earth was still hot, and etc, that I began on Trollope’s series. I think I started out of order with the Barchester novels, and then moved on to the Pallisers; and THE PRIME MINISTER’S CHILDREN is the last. Now all that lies before me is his stand-alone single books, re-reading of the series in retirement, and of course sad and lonely death.  Like Edith Wharton, Junot Diaz is clearly working through some powerful personal issues. Almost every single one of these stories is about regret for infidelity, and is full of a kind of steaming pain, while also being strangely hilarious.

Like Edith Wharton, Junot Diaz is clearly working through some powerful personal issues. Almost every single one of these stories is about regret for infidelity, and is full of a kind of steaming pain, while also being strangely hilarious.

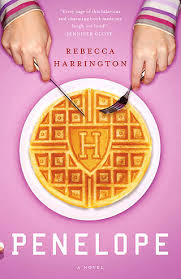

This is a book about the Harvard experience by someone recently graduated from Harvard. It begins well; here is the first description of the central character: “Penelope Davis O’Shaunessy, an incoming Harvard freshman of average height and lank hair,” which I found entertaining.

This is a book about the Harvard experience by someone recently graduated from Harvard. It begins well; here is the first description of the central character: “Penelope Davis O’Shaunessy, an incoming Harvard freshman of average height and lank hair,” which I found entertaining.