I don’t know if I’m getting less disciplined in my old age, less interested in the wider world, or if everything’s just getting more crap. I’ve been abandoning books left and right. Here’s an overview:

PORTRAIT OF A LADY by Henry James: This should be the sort of book I like. I love a fat old novel. I’ve tried it before, one singular Christmas in Tallahassee when I was nineteen, and abandoned it then, but I thought I should try again, because the credentials are so good. But God, it was hard going. No using one word when ten would do, no need for a plot if you can put in a description. So I gave up.

TOM JONES by Henry Feilding: In a depressing turn on events, someone seeing the title asked me if it was a biography of the singer. I felt very literary, and yet I just couldn’t make it all the way through. It was fun, but all very dawn of the novel, lots of disconnected episodes and a strong supposition that we don’t need any background on the political machinations of Bonnie Prince Charlie.

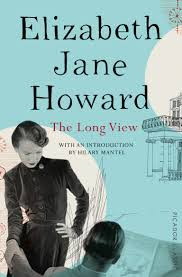

THE LONG VIEW by Elizabeth Jane Howard: I love the ‘Staff Picks’at London’s bookstore Foyle’s (independent: I’m in hourly expectation of its closing), so when the cashier was moist eyed with enthusiasm when I bought this novel I was ready to be excited. The beginning was great: “This, then, was the situation. Eight people were to dine that evening in the house at Campden Hill Square. Mrs Fleming had arranged the party (it was the kind of unoriginal thought expected of her, and she sank obediently to the occasion) to celebrate her son’s engagement to June Stoker.” Unfortunately while well written, I found it hard to get engaged. It’s about an unhappy marriage in the 30s, and I can only think that this was all perceived as more tragic back then. I spent most of the book thinking JUST GET A DIVORCE THEN JESUS. So I had to give up

THE LEOPARD by Guiseppe de Lampedusa: I actually read this in college, after a professor specifically recommended it to me, and thought I’d re-try it now. It’s a story of a decadent old nobleman at the time of Italian unification, and while interesting in many ways there was way too much pontificating about how ‘Sicily is weighed down by history’ and ‘Sicilians are an exhausted people,’ and so on. Once has to listen to a lot of addled political talk from people who don’t know what they’re on about in daily life; it’s not what I need from literature