I feel bad to say it but this book made me like Amy Poehler a little less.

The early section, where she talked about her childhood (blissful) and her struggle to get into comedy (inspirational in retrospect) was interesting. But the lengthy last part, about her current famous self was sort of dull. Maybe this is because I do not really know how famous Amy Poehler is, and do not really know her famous friends. Thus anecdotes about how much she laughed backstage eating burritos with Will Arnett, whoever he is, leaves me cold.

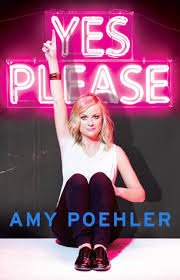

Also deeply unfortunate is a part where she goes to Haiti. I know it’s not very kind, but I include a picture she puts in her book – apparently without irony – that shows you how she thought about that experience.

In the preface, she talks about how hard it was to write the book, and shares her struggle as to what should go in it:

“In this book there is a little bit of talk about the past. There is some light emotional sharing. I guess that is the ‘memoir’ part. There is also some ‘advice’, which varies in its levels of seriousness. Lastly, there are just essays, which are stories that usually have a beginning and an end, but nothing is guarantted.”

And perhaps that’s a bit the problem. I’m not sure you should write a book, if you’re not quite ready to put yourself in it. Though perhaps I’m judging her against a ludicrously high bar, of Proust and Knausgaard – but then, if you set out to write a memoir, that’s just who the competition is.

It’s probably best if she sticks to screenplays. Because despite the book I continue to like her shows, and I love that her and Tina Fey are writing and making movies with women as central characters. And some bits of the book were to me inspirational, not least her ability to claim confidence as her right. Let’s end on an inspirational note, from Poehler: “I believe great people do things before they are ready. This is America and I am allowed to have a healthy self esteem”

So perhaps she wrote the book before she was ready, but perhaps that’s not such a bad thing.