A very compelling story about a young Irish girl who gets pregnant and comes to England to find the father with whom she had a holiday romance. She doesn’t find him, but she does find what we slowly conclude is some kind of SPOILER ALERT serial killer. This makes it sound like it’s cheesy, but it’s really not. Trevor is a really gifted writer and tells the story from both POV in a very compelling way. My main take away is, THANK GOD FOR FEMINISM. This poor girl is so messed up that she really is barely able to advocate for herself in even the most basic ways, and that’s before she meets the serial killer.

WHAT I READ IN 2024

This year I have read 79 books, the most since 2011. I was surprised; it didn’t feel like any more than normal. Though there was a Greek beach vacation in there where I was reading about a book a day, so perhaps that’s where the numbers come from.

In real life I read in 6 countries, but all in just the one year, of 2024. In reading life I went everywhere, Cairo in the 1950s, Polynesia with Captain Cook, medieval Norway, the Spanish Flu in Connecticut. Looking at this list, I realize what I read shapes what I think about to the point where I do sort of wonder who I’d be without it. Horrifying prospect.

Example, I can hardly look at a plate of food at the moment without thinking of William Woodruff’s memoir of his impoverished 1920s childhood, THE ROAD TO NABEND, in which he explained that they were so hungry that “all meals were our favourite meals.” I don’t think I’ve complained about a dinner since.

Best of the year this year: I have to give it up to Peter Carey’s THE TRUE HISTORY OF THE KELLY GANG, a book about Australian outlaws that is a triumph of narrative voice; SEVENTEEN by Joe Gibson, a really sad memoir about a teacher grooming a male student, and the loss of his twenties to her narcissism; and PRAIRIE FIRES by Caroline Fraser, an unexpectedly wonderful biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder (a writer I don’t even care about). This is my first year ever I think where highlights were more non-fiction and memoir than fiction. Honourable mentions have to go to LOVE LESSONS by Joan Wyndham, astonishing diaries about a young woman’s sex life in the second world war, and don’t laugh, but to THE WOMAN IN ME by Britney Spears, a book that has left me amazed no one has gone to jail yet for what they did to her.

Here’s the list:

THE SINGULARITY IS NEARER by Ray Kurzweil

PRIVATE CITIZENS by Tony Tulathimutte

TROUBLES by JG Farrell

THE SEIGE OF KRISHNAPUR by JG Farrell

WIGS ON THE GREEN by Nancy Mitford

THE EMPEROR by Ryszard Kapuscinki

GERMINAL by Emile Zola

THE MAN OF PROPERTY by John Galsworthy

DINNER WITH VAMPIRES by Bethany Joy Lenz

TOM LAKE by Ann Pratchett

PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK by Joan Lindsay

WILD by Cheryl Strayed

INTERMEZZO by Sally Rooney

A CONSPIRACY OF PAPER by David Liss

THE MARS ROOM by Rachel Kushner

NEVER LET ME GO by Kazuo Ishiguro

THE STRANGER AT THE WEDDING by AE Gauntlett

LITTLE BASTARDS by Mildred Kadish

TOWELHEAD by Alicia Erian

THE DAIRIES OF MR LUCAS: NOTES FROM A LOST GAY LIFE edited by Hugo Greenhalgh

PRAIRIE FIRES: THE AMERICAN DREAMS OF LAURA INGALLS WILDER by Caroline Fraser

DOGGERLAND by Ben Smith

AN HONEST WOMAN: A MEMOIR OF LOVE AND SEX WORK by Charlotte Shane

NEVER SAW ME COMING by Tanya Smith

SHEEP’S CLOTHING by Celia Dale

LIVES OF GIRLS AND WOMEN by Alice Munro

ENEMY WOMEN by Paulette JilesTHE WIDE WIDE SEA by Hampton Sides

ORDINARY HUMAN FAILINGS by Megan Nolan

THE MINISTRY OF TIME by Kaliane Bradley

BANAL NIGHTMARE by Halle Butler

LONG ISLAND COMPROMISE by Taffy Brodesser-Akner

THE FUTURE by Naomi Alderman

THE ROAD TO NAB END by William Woodruff

THE BRIDGE OVER THE RIVER KWAI by Pierre Boulle

THE TRUE HISTORY OF THE KELLY GANG by Peter Carey

THE FLATSHARE by Beth O’Leary

CONVERSATIONS WITH GOETHE by Johann Peter Eckermann

SEVENTEEN by Joe Gibson

ALL FOURS by Miranda July

GREEN DOT by Madeleine Gray

THE INHERITORS by William Golding

SO LONG, SEE YOU TOMORROW by William Maxwell

SMALL FRY by Lisa Brennan-Jobs

PROMISE AT DAWN by Romain Gary

SATURDAY NIGHT AND SUNDAY MORNING by Alan Sillitoe

THE WALL by John Lanchester

FUNNY STORY by Emily Henry

MONEY by Martin Amis

YOU AND ME ON VACATION by Emily Henry

YOU, AGAIN by Kate Goldbeck

ADVENTURES IN MASHONALAND by Rose Blennerhassett and Lucy Sleeman

COLD CREMATORIUM by Jozsef Debreczeni

THE RECOLLECTIONS OF AN ELEPHANT HUNTER 1864-1875 by William Finaughty

SALLY IN RHODESIA by Sheila McDonald

A YEAR ON EARTH WITH MR HELL by Young Kim

HELP WANTED by Adelle Waldman

SUPER-INFINITE by Katherine Rundell

STRAIT IS THE GATE by Andre Gide

LOVE LESSONS and LOVE IS BLUE by Joan Wyndham

SALEM’S LOT by Stephen King

DIRTBAG MASSACHUSETTS by Isaac Fitzgerald

WEIRDO by Sarah Pascoe

THE MANDIBLES by Lionel Shriver

WITH LOVE, FROM COLD WORLD by Alicia Thompson

TRAVELS INTO THE INTERIOR OF AFRICA by Mungo Park

THE PUMPKIN EATER by Penelope Mortimer

CHARLOTTE GRAY by Sebastian Faulks

THE SUITCASE by Sergei Dovlatov

BEER IN THE SNOOKER CLUB by Waguih Ghali

THEY CAME LIKE SWALLOWS by William Maxwell

SOUTH RIDING by Winifred Holtby

AT FREDDIE’S by Penelope Fitzgerald

OLAV AUDUNSSON: VOWS by Sigrid Undset

THE WRONG KNICKERS by Bryony Gordon

THE WOMAN IN ME by Britney Spears

NORMAL WOMEN by Ainslie Hogarth

POOR THINGS by Alasdair Gray

THE TRIO by Johanna Hedman

THE SINGULARITY IS NEARER by Ray Kurzweil

This book is a fantastically named sequel to his first, THE SINGULARITY IS NEAR. The Singularity is moment at which our brains are able to meld with a computer, so we will – according to him – be able to be fantastically more intelligent. A bit like the leap from Neanderthal to today.

It’s a book absolutely bristling with ideas – I highlighted lots of it. Like, for example, do you know the odds of the sperm and egg meeting to make you was 1 in 2 million trillion? And then go back through all the people who had to meet and mate to produce your parents, to see how lucky you are to be alive. Even wilder, he talks about how many things had to go right for life to have emerged on earth at all; apparently it is the same likelihood as a tornado blowing through a junkyard and assembling a Boeing 747.

He has lots of big ideas for the future – for example, for when nanotechnology will be able to print anything, because it will be able to assemble stuff at atom level. So lithium will no longer be precious; nor will diamonds. He believes the world is getting better (did you know deaths from war in prehistory were about 500/100K; now they are 4/100K, even counting nuclear weapons?), and will continue to get better quickly. He makes some good arguments, pointing out how unimaginable landing on the moon was in the early 1900s, when no one had even flown yet.

I struggled a lot with all this talk of the ‘one way march of progress.’ I see what he means, but on the other hand, I’m not sure I do. What about the fall of Rome? What about the dangers of AI? I hate to say it, but all this boundless optimism just said one thing to me, and that one thing was: boomer. I get it, your life has just been one long upward swing. Here’s fingers crossed for the rest of us.

PRIVATE CITIZENS by Tony Tulathimutte

This book is very more-ish and seethes with verbal energy. Try this:

“If you preferred the indoors, everyone assumed you were scared of life and emotionally stunted. That wasn’t it. . . . Sure, it was nice to have some fresh air while he smoked. But he was myopic, hard of hearing, congested – reality was lo-fi, slow and obstructing, too cold or too bright, filled with scrapes, sirens, hidden charges, long distances, pollen, and assholes”

It was also kind of hilarous; one character, we are told, has seen ‘most of’ the porn on the internet. Given that this is set in 2007, what is eerie is I guess this might just conceivably be possible. Today I suppose it would take several lifetimes. The book tells the story of four friends living in San Francisco a couple of years after they graduate from Stanford. About two-thirds of the way through, I started to get exhausted. Everyone was so self-harming! There was anorexia, self hatred based on race, failing to take your anti-psychotics, lying about rape, and that’s just the first few I can think of. And of course there was no redemption: it was just self-harm and self-harm some more. But weirdly I still enjoyed it.

TROUBLES by JG Farrell

This author was kind of a jock at university. Then he caught polio, poor guy, just a couple of years before the vaccine was invented, and had to abruptly enter an iron lung to stay alive. Sport’s loss was literature’s gain, because he’s a wonderful writer. This book tells the story of a WWI veteran who goes to visit a woman he met in Brighton during his leave. She says she is fiance; he can’t remember if she is or not. It gets weirder from there. The alleged fiance lives in an enormous decaying hotel in Ireland, and dies almost immediately after he gets there. For some reason he stays on, while the hotel crumbles around him. A bunch of stuff then happens that has something to do with Irish political history, I could not follow all that. But I enjoyed it nonetheless. Here is a taste, when they brought in the family dogs to try and chase out the huge family of cats who were living in abandoned rooms:

“But it had been a complete failure. The dogs had stood about uncomfortably in little groups, making little effort to chase the cats but defecating enormously on the carpets. At night they had howled like lost souls, keeping everyone awake. In the end the dogs had been returned to the yard, tails wagging with relief. It was not their sort of thing at all.”

THE SEIGE OF KRISHNAPUR by JG Farrell

I found this book in my house, but have no idea where or when I got it. It’s part of the EVERYMAN’S LIBRARY series – a fantastic series I used to read a lot of back when I haunted the Harare City Library – so I assume I picked it up based on that alone. And once again EVERYMAN’S LIBRARY has come up with the goods. I’d never heard of this JG Farrell, but this is a banging book. It is a fictionalization of the Siege of Lucknow in 1857, which I’d also never heard of, in which a group of English colonials withstood a long siege by the rebellious Indian army. It is a hair-raising story of delicately brought up people reduced to eating rodents, but it is a also a hilarious book of ideas. Try this description of a young man:

“From the age of sixteen when he had first become interested in books, much to the distress of his father, he had paid little heed to physical and sporting matters. He had been of a melancholy and listless cast of mind, the victim of the beauty and sadness of the universe. In the course of the last two or three years, however, he had noticed that his sombre and tubercular manner was no longer having quite the effect it had one had, particularly on young ladies. They no longer found his pallor so interesting, they tended to become impatient with his melancholy. The effect, or lack of it, that you have on the opposite sex is important because it tells you whether or not you are in touch with the spirit of the times, of which the opposite sex is invariably the custodian.”

This gives you a flavour. It would have been really easy to write a book of stereotypes, because these poor starving people are so obviously getting what they richly deserve, but somehow he avoids it. Strongly recommend! So strongly in fact that I immediately read his next book TROUBLES. Of which more shortly.

WIGS ON THE GREEN by Nancy Mitford

I love Mitford’s THE PURSUIT OF LOVE. According to my blog I’ve read it an embarrassing 7 times. I was thus delighted to come across this book, her third and a very obscure one, quite accidentally. (By accidental, I mean in the Waterstones in John Lewis, when I was looking for a laundry hamper. Why is there a Waterstones in John Lewis? Why is it by the laundry hampers?)

I don’t like any of her other books, but hope springs eternal I guess. Hope was misplaced. It’s dated and awkward. Of interest though is that she was worried about being sued by her sister, the famous fascist Unity Mitford, as it is in part a satire of Unity’s strange, jokey right-wing sensibility as the ‘greatest heiress in England’ (she was 6 ft 1).

As a child, apparently, Unity shared a room with her other sister, Jessica, a committed communist. They divided the room in half with chalk, one side with pictures of Lenin and the other with swastikas. In later life, Unity travelled to Germany where she got a lot less jokey. Apparently she actually dated Hitler, or was at least used by Hitler to make Eva Braun jealous. She later shot herself when war was declared, which I for one am not at all sorry about.

What does inspire me about this book, in a strange way, is how bad it is. The style is close to THE PURSUIT OF LOVE but also very far away. It’s inspiring to see how someone can work through from this very uneven early work to that classic.

THE EMPEROR by Ryszard Kapuscinki

Here is a book in which a journalist seeks out and interviews members of the court of Haile Selassie, the last emperor of Ethiopia, immediately after he is deposed. This is not too easy, as they either dead or in hiding. He is mostly able to find the most junior servants. The guy whose job was to put the pillow under his majesty’s feet; the guy whose job was to clean up after his majesty’s dog; the guy whose job was to bow every hour on the hour, so the emperor could keep track of time passing. It’s an interesting picture of what power does to people. Some say that the interviews are a bit too on the nose, and that in fact the whole thing is a commentary on the dictatorship in Kapuscinki’s native Poland. I don’t know that it makes that much difference; one great truth in life is that one autocrat is much like another.

Particularly interesting was how Selassie lost power, in inches, to the military council named the Derg, which itself became a pretty robust dictatorship basically immediately. I have been to a museum about this in Addis, where they directly display some of what they dug up from mass graves of the period, including heart-breaking passport photos of hopeful students with enormous 70s hair who laid down their lives for a better Ethiopia. I’ve also been to Selassie’s palace, where you can see the his-n-hers bathroom set up he had (pink and blue) complete with bullet holes in the mirrors from when things got real at the end.

A sad and weird read.

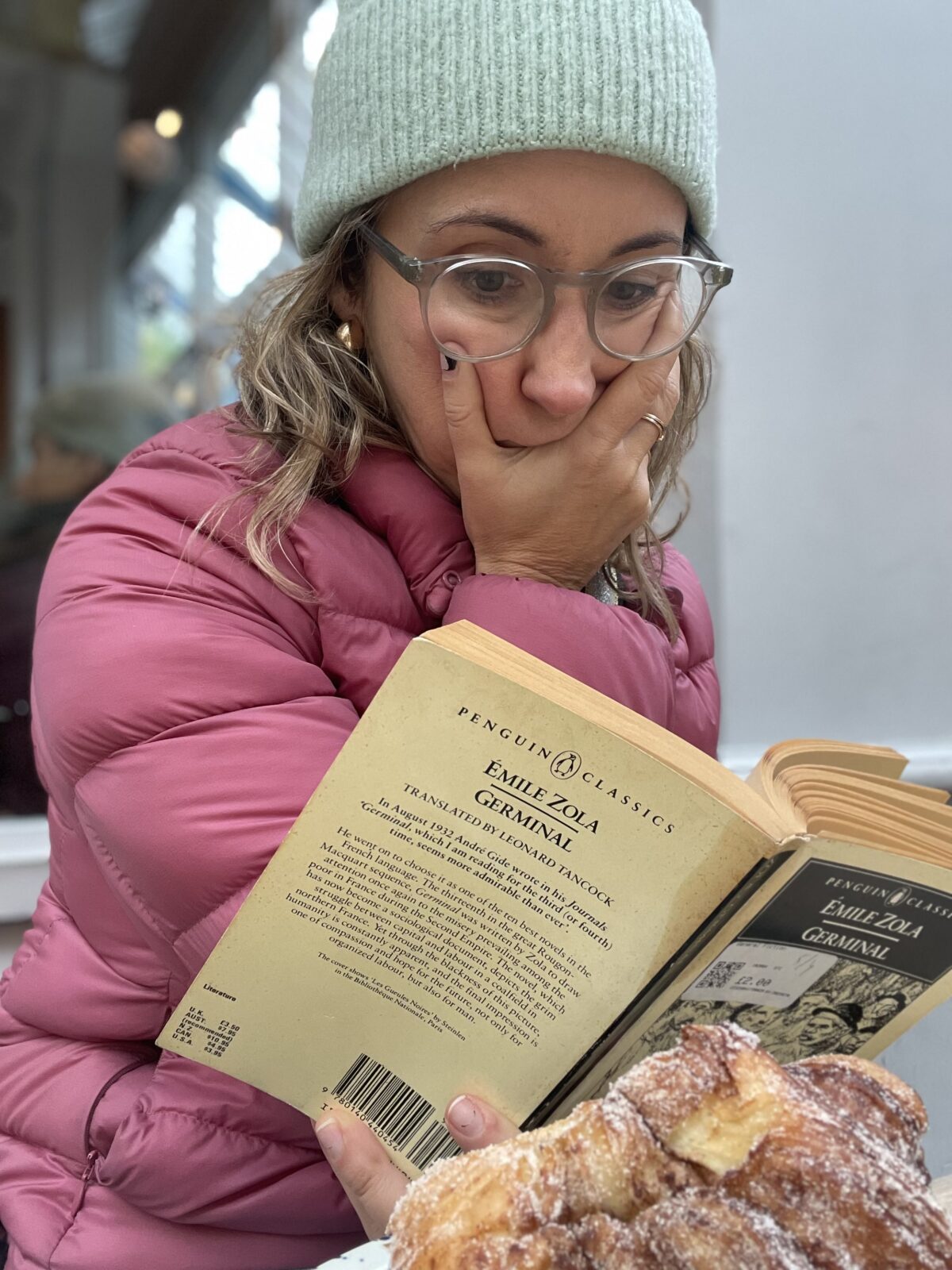

GERMINAL by Emile Zola

I thought I’d give this novel a bash to see how far my attention span has degraded. In my teens and twenties the vast majority of what I read was massive 19th century novels, and I was curious if I still had the appetite for all that tiny text, description of landscape, and casual misogyny. Good news: yes I do!

This one tells about a man walking through 19th century France looking for a job. He is facing starvation when he lucks into work in a coal mine. Cue a lot of interesting detail about 19th century mining practices. As you can imagine its not good: while they don’t get to have much to eat, they do get to have coal lung, and lets not even get into the ponies permanently trapped down there.

I was kind of hoping this story might be about how this guy was delighted to escape from starvation to near-starvation, and went on to build a happy family life in the mines. LOL no. He is inspired by the idea of communism and eventually convinces everyone else to strike. At this point, it started to feel very much like THE JUNGLE by Upton Sinclair (same story, except 1930s/America/ abbatoir), a book that wrecked me in a Chicago airport maybe twenty years ago. I could just see where we were going with idealism crushed, people starving, immortal logic of capitalism triumphant and etc, and I just couldn’t bring myself to go through it. So I guess the good news is my attention span’s fine, but the bad news is my emotional resilience is SHOT.

THE MAN OF PROPERTY by John Galsworthy

This is the first in a series of novels which is part of how Galsworthy won the Nobel. I enjoyed it, but I am not sure if I will read the whole 1000 page saga which I am told is ‘three novels and two interludes,’ wtf is an interlude. Anyway, this first novel tells about the unhappy marriage of Soames Forsyte and his wife Irene. Forsyte comes from a robustly bourgeois background, while Irene is poor. I have not googled it but I am 100% sure Galsworthy comes from a family with money, because he spends a lot of time banging on about how awful families with money are, how obsessed with property, etc

The couple have little in common and she SPOILER ALERT begins an emotional affair with her husband’s architect. She had already ‘locked her door’ to Soames, and eventually he becomes so enraged that he ‘asserted his rights and acted like a man’. I was really impressed that a book written this early takes marital rape so seriously. Irene is extremely distressed, and the architect is too, ending up killed in a carriage accident. Soames meanwhile is upset too, but mostly because he can’t understand why Irene won’t just accept that she, just like their big house, is his property.