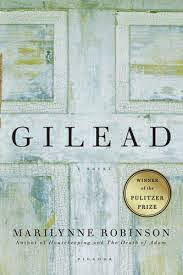

This is a marvelous book. Nothing much happens in it – it’s just the everyday diary of a elderly pastor in the Midwest – but I felt like blubbing all the way through. He’s near the end of his life, and knows it, so much of the diary is about the joy of that ‘every day’. He married late, and so his son is very young. Here’s the description:

. . . Your hair is straight and dark, and your skin is very fair. I suppose you’re not prettier than most children. You’re just a nice looking boy, a bit slight, well scrubbed and well mannered. All that is fine, but its your existence I love you for, mainly. Existence seems to me now the most remarkable thing that could ever be imagined. I’m about to put on imperishability.In an instant, in the twinkling of an eye

If we are supposed to get better, and wiser, as we get older, its only through persistent struggle, and this diary is much also about that struggle. He gives us much good advice, such as “Adulthood is a wonderful thing, and brief. You must be sure to enjoy it while it lasts.” Or:

In every important way we are such secrets from each other, and I do believe that there is a separate language in each of us, also a separate aesthetics and a separate jurisprudence. Every single one of us is a little civilization built on the ruins of any number of preceding civilisations, but with our own variant notions of what is beautiful and what is acceptable – which I hasten to add, we generally do not satisfy and by which we struggle to live

Perhaps what gives this book its particular melancholy is the extent to which the pastor has accepted all that is lost. “When I was a young boy I used to get up before dawn every dawn of the world to fetch water and firewood. It was a very different life then. I remember walking out into the dark and feeling as if the dark were a great, cool sea and the houses and the sheds and the woods were all adrift in it, just about to ease off their moorings. I always felt like an intruder then, and I still do, as if the darkness had a claim on everything, one that I violated just by stepping out my door. This morning the world by moonlight seemed to be an immemorial acquaintance I had always meant to befriend. If there was ever a chance, it has passed. Strange to say, I feel a little that way about myself.”

I was also struck in reading it by the great heritage that the Bible has been to the world of literature. This book just reeks of Bible, and I mean that in a good way. Here he speaks about what it will be like to be re-united with his dead wife when he dies: “I have wondered about that for many years. Well, this old seed is about to drop into the ground. Then I’ll know.”

This was Robinson’s second novel, 25 years after her first. I don’t know if she spent all 25 years writing it, but if so it was time well spent. It might have taken a few years just to come up with this:

This morning Kansas rolled out its sleep into a sunlight grandly announced, proclaimed throughout heaven – one more of a very finite number of days that this old prairie has been called Kansas, or Iowa. But it has all been one day, that first day. Light is constant, we just turn over in it.