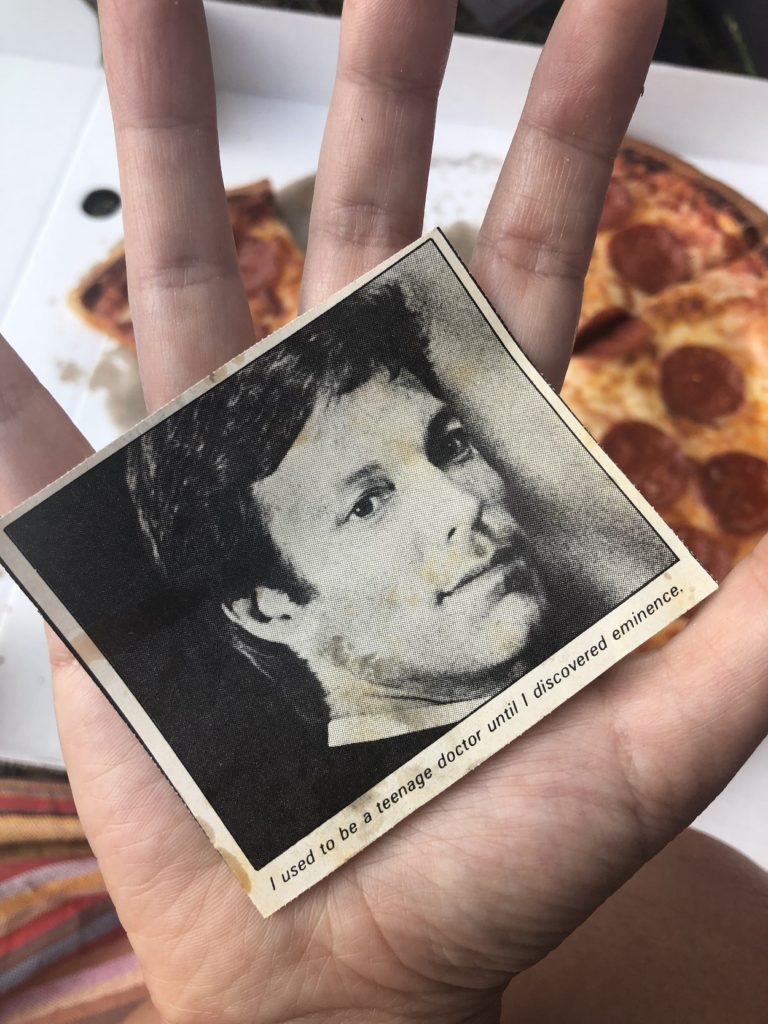

“Of what import are brief, nameless lives . . . to Galactus?”

(Fantastic Four, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, Vol 1, No 49, April 1966)

And so begins this wonderful novel. Followed by, bizarrely, an entire poem by Derek Walcott, an important Caribbean poet.

This gives you a kind of sense of what a seriously loopy book this is, verging wildly from the highly literary, to pop culture, from English to Spanish, from Trujillo’s dictatorship in the Dominican Republic to contemporary New Jersey.

Oscar Wao is a fat guy who loves sci-fi to an unhealthy degree, and is permanently in hope of finding love with a lady. His story is intercut with that of his sister, who flees the US for their ancestral homeland of Dominican Republic, and with the stories of his grandfather and mother, and of what made them flee the DR (as he calls it) for America.

Oscar’s grandfather was tortured and murdered by the Trujillo regime, because he refused to offer his oldest daughter up freely to Trujillo to be raped. Oscar’s mother, the youngest daughter, was thus left an orphan. She grew up and was eventually forced to flee the DR after getting entangled in a stupid relationship with the husband of Trujillo’s sister. Oscar’s own story eventually leads him back to the DR, where he finally finds love (with an elderly prostitute) and is eventually murdered by her boyfriend’s heavies.

Actually as I write it out it sounds like rather a miserable and melodramatic tale. But so sparkling and irreverent is the voice of the novelist, so sure the comedy, so accurate the observation – especially of the world of fat dorks – that in fact the book is a non-stop delight.

I was particularly struck by how Diaz managed to mix together the many aspects of his life – first and third world, pop and literary culture – into one coherent identity. This is something I certainly can’t seem to achieve.

The poem that begins the novel, after talking about Derek Walcott’s varied backgrounds, ends:

“I’m just a red nigger who love the sea,

I had a sound colonial education,

I have Dutch, nigger, and English in me,

and either I’m nobody, or I’m a nation”

PS. Zimbabwean? Want to feel a certain someone’s not that bad? Check out Trujillo’s dictatorship here. He eventually died in an assassination, but I must point out he had serious prostate problems too. . . Holding thumbs!