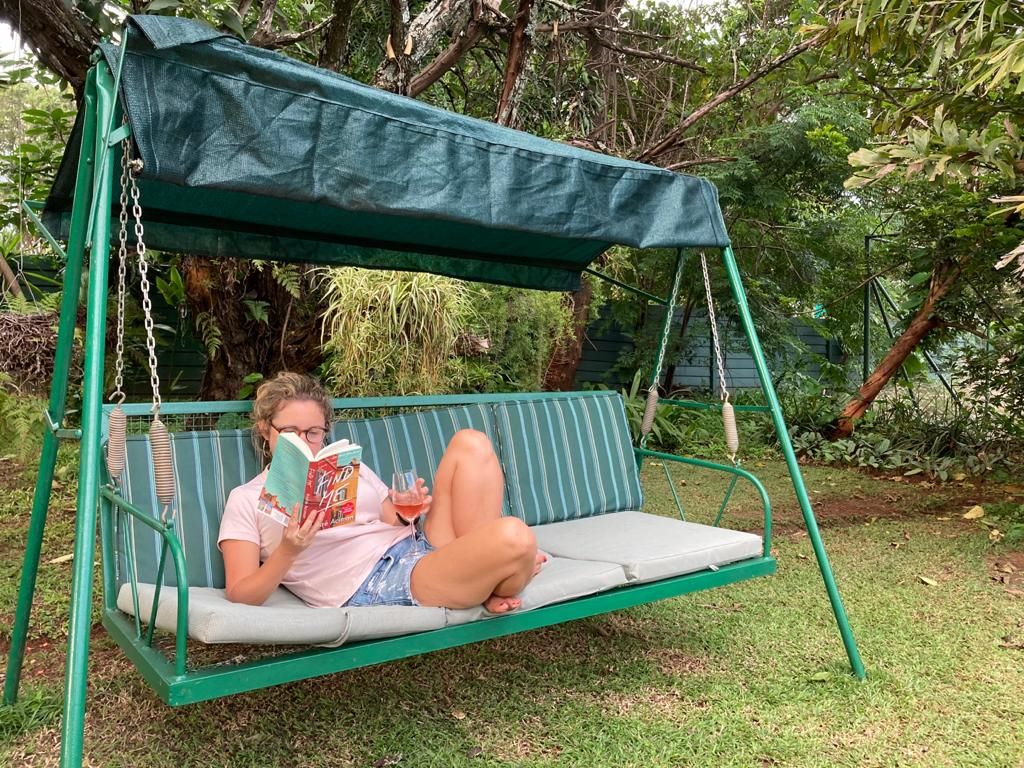

About ten pages into this book, I felt like I was getting into a hot bath. I just got ready to seriously relax. It’s exactly the sort of book I like: one that gives you a break from your own life, by deeply involving you in someone else’s.

It tells the story of a little boy being raised on some quite rough council estates by his alcoholic mother. I would bet heavy money that this book, while marketed as fiction, is based on the author’s own childhood. There is a certain subset of books in which the detail of daily life is so vividly captured that it can only come from a child’s eye, and ideally a child with a ton of trauma. It’s Glasgow in the 1980s, a place and a time I’ve never given a second thought to, and now I feel like I have a real experience of it. It joins such bizarrely disparate periods as Trinidad in the 1950s (courtesy, A HOUSE FOR MR BISWAS) and the Dominican Republic in the 1960s (courtesy, FEAST OF THE GOAT read on a particularly hallucinatory 12 hour bus ride to Acupulco).

I won’t go on about everything I thought was wonderful about this book, but let me just leave you with this:

The other taxi drivers had taken on that familiar shape of men past their prime, the hours spent sedentary behind the wheel causing the collapse of their bodies, the full Scottish breakfasts and the snack bar suppers settling like cooled porridge around their waists. Eventually the taxi hunched them over till their shoulders rounded into a soft hump and their heads jutted forward on jowled necks. The ones who had been at the night shift a long time had turned ghostly pale, their only colour was the faint rosacea from the years of drink. These were the men who decorated their fingers with gold sovereign rings, taking vain pleasure from watching them sit high and shiny on the steering wheel

And that’s just taxi drivers! Imagine everything else that’s in there