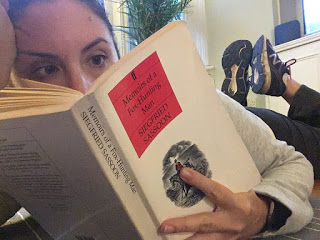

I was surprised to find that this book, MEMOIRS OF A FOX-HUNTING MAN, is mostly about fox hunting. I am not too sure why I thought that the title was going to be metaphorical, like maybe the fox was going to be happiness or something, but I can report the fox is definitely an actual fox. Sassoon really liked hunting, and thinks (perhaps justifiably) that those people buying books about fox-hunting might like it too. And want to read about it in great detail.

Aside from the majority of the content, I quite enjoyed this book. Sassoon is a lovely writer, and I love a good memoir. Here’s the first line:

My childhood was a queer and not altogether happy one.

You and everybody, Siegfried. But there follows a lovely few hundred pages of clear, unfussy prose, such as is rare to find and a joy to read. It’s simplicity that requires great skill. Initially I struggled with some class-based rage. Sassoon has a medium size unearned income. He thus enjoys spending his twenties hunting (four days a week in the winter) and playing cricket (four days a week in the summer). He has a fabulous time with his “friends” Stephen and Dick. (I have not wikipedia-ed him, but he is for SURE gay). He is rather exceeding his income, as horses are apparently expensive, so his guardian tries to interest him in reading law, but he reacts with horror at the idea of being trapped in a London office. You and everybody, Siegfried.

When the First World War comes he signs up. The book takes an abrupt and terrible turn. After pages of hounds and horses and hunting calls we have, in a conversation on signing up:

It may be inferred that he had no wish that I should be killed, and that . . . but he would have regarded it as a greater tragedy if he had seen me shirking my responsibility. To him, as to me, the War was inevitable and justifiable. Courage remained a virtue. And that exploitation of courage, if I may be allowed to say a thing so obvious, was the essential tragedy of the War, which, as everyone now agrees, was a crime against humanity.

It’s a neck-snapping change of pace and environment. If Sassoon for the first two hundred pages seems strangely childish and idealistic, with what reads to us today as a rather babyish respect for tradition and authority, he grows up fast. His friends and ‘friends’ start to die, and he goes through a phase of wanting to die too; as he puts it, if a man “laid down his life for his friends it was no part of his military duties.” You know things are bad when someone starts to talk about what ‘a lovely train’ the 5.30 from Paddington used to be. Truly, I can’t imagine how bad things would have to get for a Londoner to reminisce fondly about their commute.

Sassoon gets to go home on leave, and sits surrounded by paintings of his horses, realising that his “past is beginning to wear a bit thin.” Apparently the next book is MEMOIRS OF AN INFANTRY OFFICER. I’m going to try it. I expect much information about Infantry Officers.