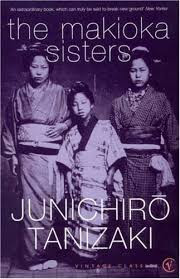

Regarded by many as the finest novel of twentieth century Japanese literature, THE MAKIOKA SISTERS is the story of four sisters in the years leading up to World War II.

It’s really a rather sad book, though based on the plot alone I wouldn’t be able to say why. The plot is: they want to get the two younger sisters married. And I guess it ends happily, with both sisters on their way to the altar. This is the traditional happy ending. But here you go with the bizarrely anti-climatic last line of the book:

Yukiko’s diarrhea persisted through the twenty-sixth, and was a problem on the train to Tokyo.

That gives you the flavour. This book is much less about plot, than it is about all the many ordinary days that make up all our lives between plot points. You meet the love of your life; then you still go to the dentist that afternoon. You still go to work. One day he will propose and on that day you might be wearing tight pants or a kimono that creaks.

Based on my summary above, giving the dates it covers, you’d think it might be a book about politics, but it is almost defiantly not. It’s purely, almost aggressively, about domestic life, and life before the war. Tanizaki was writing it during the war, so my theory is that this is why; he wanted to recreate a world that was already decaying, and that is what gives it is sadness.

The sisters themselves (I am sure not coincidentally) capture this movement from past to future, with the one unmarried sister a classic Osaka lady (which I now know means reserved and delicate), and the other more modern, wearing Western clothes and even having her own business making dolls. The family is going down in the world, and the reason they are struggling to marry is they are overestimate who they can get. At the beginning they decline a perfectly nice man because his mother might be mentally ill; at the end they are glad to accept a guy with no money and a sketchy past.

It’s done with a light hand, but it’s very successful; at the end I was left feeling almost homesick for pre-war Japan. That’s if you exclude all the Beri-Beri. I wasn’t so keen on that. (I had no idea it was such a big issue in Japan. Click here for very interesting history, one of the few where the rich get what they deserve)